Regular readers will know that I’ve got a bit of a special interest in physics, having worked at the Institute of Physics before joining Datalab. And, back then, one of our main concerns was lack of diversity in the young people choosing to study physics.

This goes far deeper than gender balance: physics is less popular with disadvantaged students and those from some ethnic backgrounds, for example. But gender balance, or lack thereof, is an area that’s had a lot of attention over the years, and one that a lot of people have put considerable effort into trying to improve. Sadly, for quite a long time, these efforts seemed rather futile: at A-Level and beyond, female students made up a stubbornly small proportion of those studying physics.

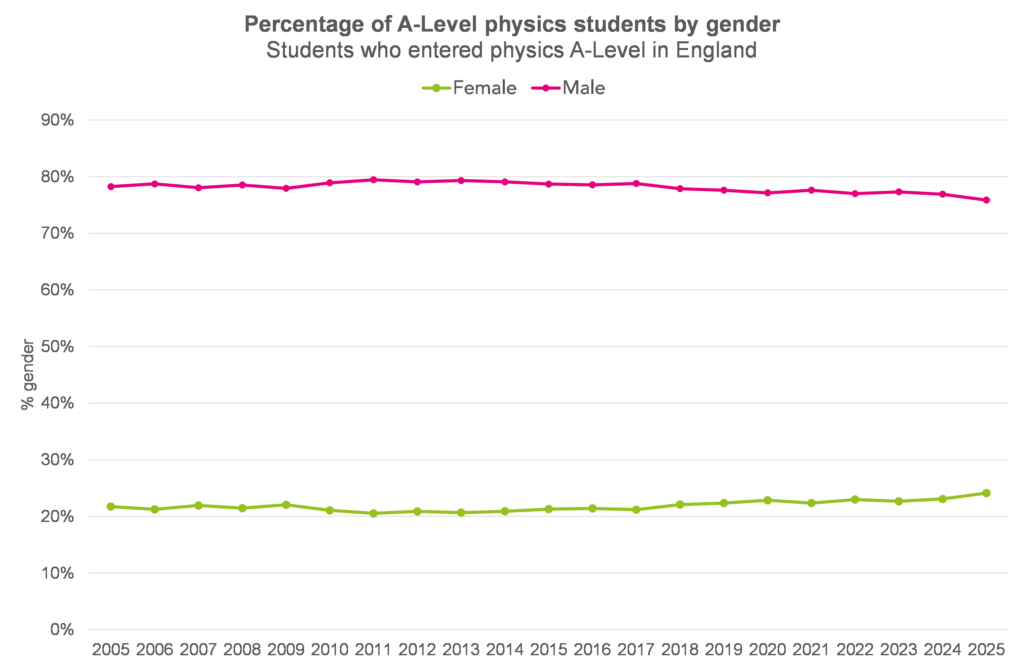

So I’m very pleased to say that there have been some signs of change in recent years. This summer, 24% of those entering A-Level physics exams were female. That might not sound very impressive, and in a sense it isn’t; physics still has the second lowest percentage of female entrants of all A-Levels. But it is the highest percentage for at least the last twenty years.

In this post, I’m going to take a detailed look at the figures and see how trends in physics compare to those in some other key subjects.

Sign up to our newsletter

If you enjoy our content, why not sign up now to get notified when we publish a new post, or to receive our half termly newsletter?

Data

This post will use A-Level exams data from the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ), from 2005-2025.

I will be using the term ‘gender’ and referring to male and female students. I do this to reflect the language used in the majority of the source data, although in recent years JCQ has begun to use the term ‘sex’.[1]

Trends in A-Level physics

Let’s start with a look at how the percentage of girls taking A-Level physics has changed over the last twenty years.

While it’s not dramatic, there has been a definite upward trend since 2013, when the percentage stood at 20.7%, until last year, when it was 24.1%. This is all the more welcome coming after years of little change from 2005-09, and a fall from 2009-11.

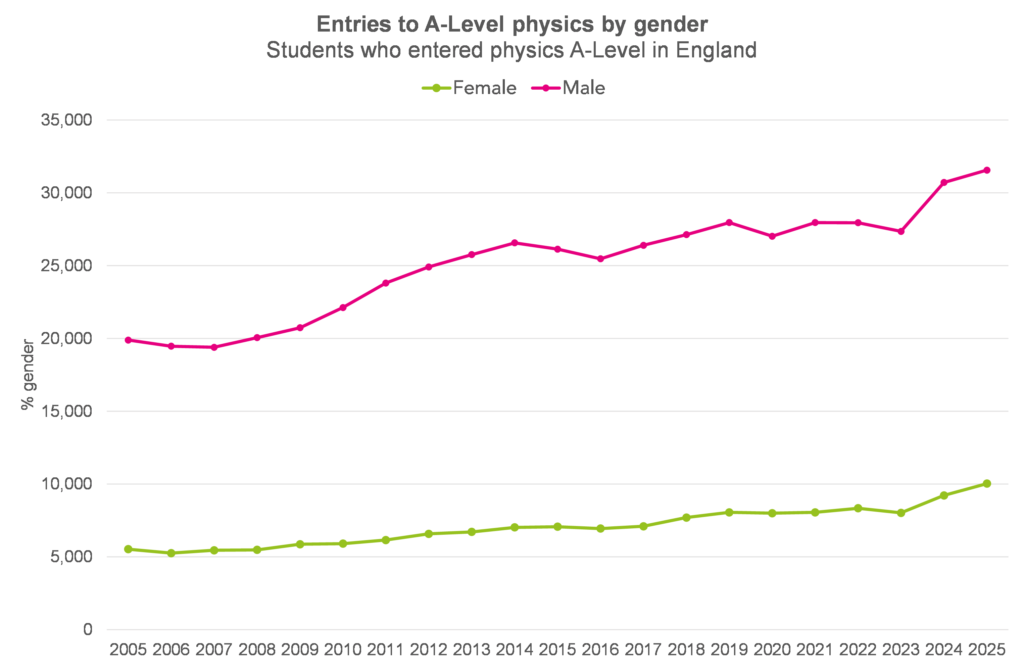

Here’s what this means in terms of entry numbers.

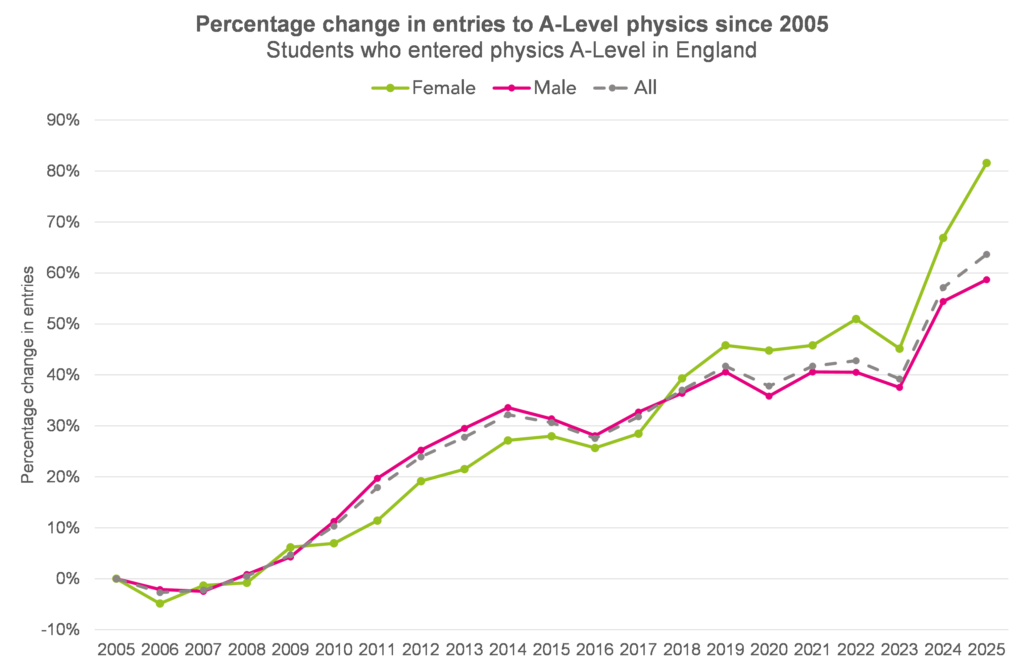

Entries to A-Level physics have been broadly increasing for both male and female students over the last twenty years. This means that the increase in the percentage of female students isn’t just caused by male students rejecting the subject. If we look at the same figures expressed as percentage change since 2005, we can get a better sense of where the change is coming from.

The increases in the percentage of female students start from 2014. At the start of this period, there was a fall in entry numbers that was sharper for male than female students, which accounts for some of the change. But the majority comes from increases in entries from female students from 2017 onwards that are sharper than increases from male students, or from decreases that are less sharp.

Comparisons with other subjects

So far, we’ve had nothing but good news: more students are studying physics A-Level, especially female students. But what about other subjects with poor gender balance? Are we seeing similar changes there, or maybe – brace yourselves – even better?

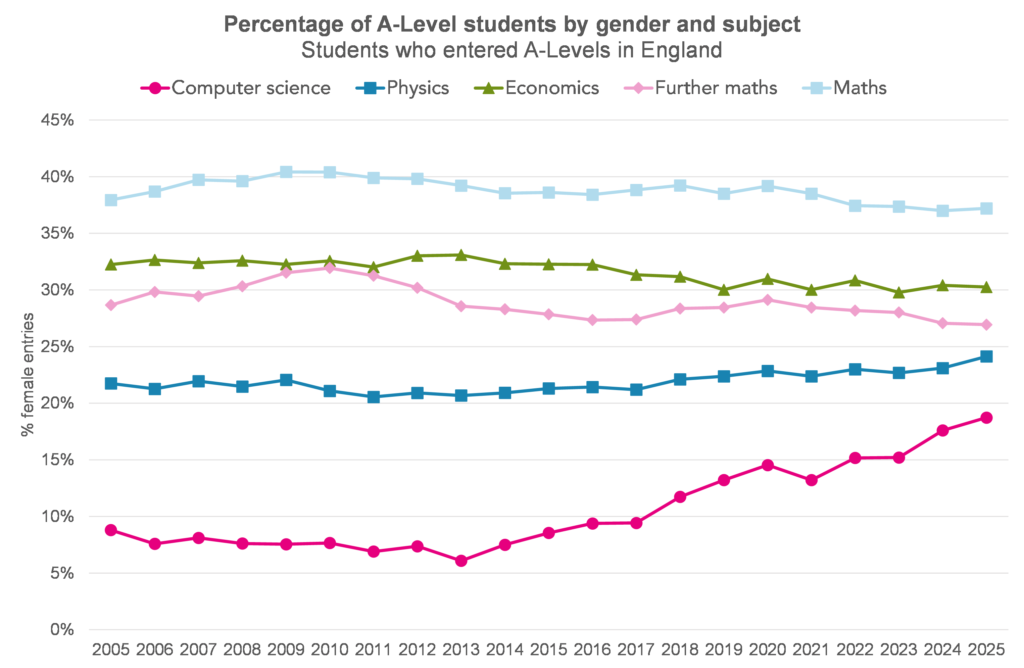

I’m going to show how the breakdown of male and female students has changed over the last twenty years for the ten least gender-balanced subjects.[2] We’ll start with subjects that are more popular with male students.

Unlike physics, economics, maths and further maths have a lower proportion of female students now than they did in 2005, although all three subjects still have more even gender balance than physics. Computer science, on the other hand, has seen a huge increase in the percentage of female students with the change starting from 2013, as it did in physics.

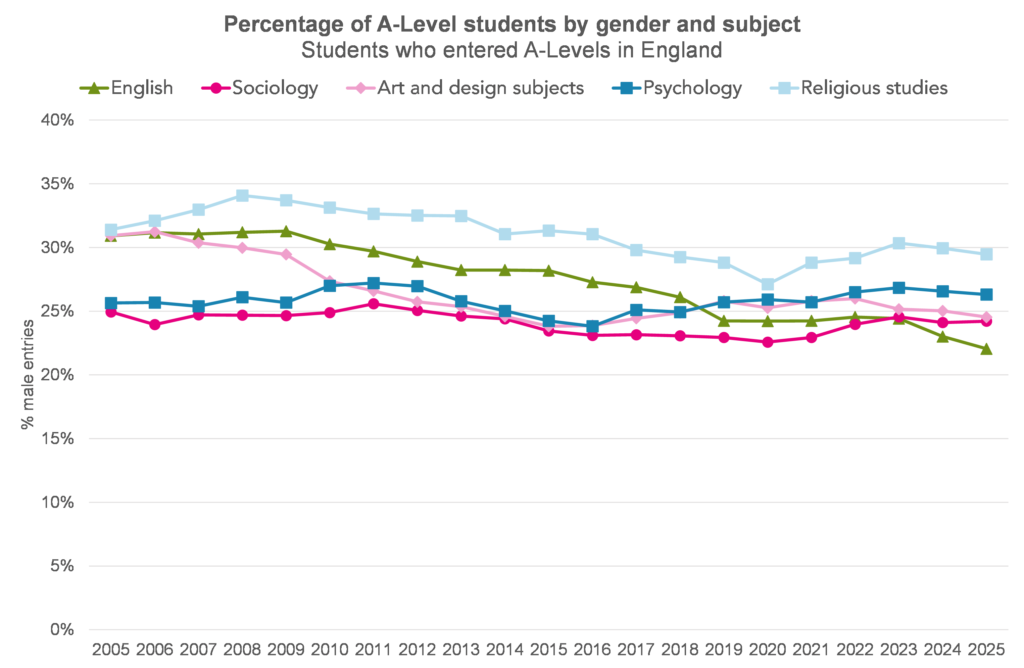

Now let’s look at subjects that are more popular with female students.

Note that we present data here for some groups of subjects. English includes English literature, English language and English language and literature. We group these subjects because that is how they are shown in the earlier years of the source data that we’re using. We also group all art and design subjects together, again because this is how they are shown in the source data.

In most of these subjects, the percentage of entries from male students has fallen since 2005; the only exception is psychology, which had a small increase from 25.6% in 2005 to 26.3% in 2025.

A science thing?

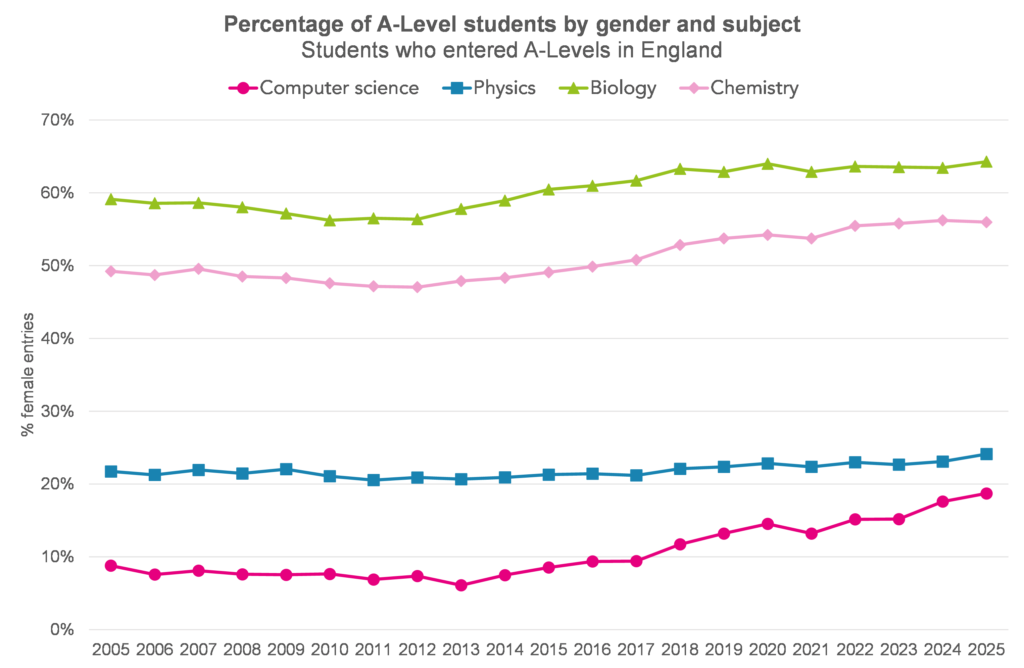

From what we’ve seen so far, it doesn’t look as though the changes in physics are part of a general trend of changes in gender balance across the board. But the comparison with computer science was suggestive: is this something that’s happening across all of the science subjects?

That does seem to be the case: in all four science A-Levels, we see an increase in the proportion of female students starting from around 2013. Biology has long had a majority female cohort, and since 2017 chemistry has been in the same boat. Physics and computer science have some way to go, but if current trends continue, they could be at 50/50 before you know it.[3]

Summing up

It might not be dramatic, but there have been consistent increases in the proportion of female students taking A-Level physics over the last twelve years. This comes alongside an increase in entry numbers generally, and seems to be part of a trend across science subjects, particularly computer science.

There is some way to go, and physics and computer science remain the A-Level subjects with the lowest proportion of female students. But, even so, it’s a good news story for the physicists.

[1]: I also do it because, to my ear, the term ‘sex balance’ sounds like it belongs on a different sort of blog. Maybe it would bring in some new readers, but ‘gender balance’ seems a bit safer.

[2]: I’ve selected the five subjects with the highest proportion of male students in 2025, and the five with the highest proportion of female students, excluding subjects for which entry numbers were not published for the whole period from 2005-25.

[3]: Assuming that the percentages continue increasing at the average rate over the last three years, we should hit 50/50 in 2070 for physics and 2103 for computer science. Before you know it!

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Would be good to have data on how uptake at all girls schools compare with co-ed schools

Hi Devesha. I’m not able to produce these figures for girls / coed schools because the datasets that I used don’t break the figures down by school type. But I have written about physics uptake in girls vs co-ed schools before – might be worth a read.

Interesting, this year my a level group is made up of only boys compared to last year which was girl heavy

Very interesting, and welcome, improvement in uptake. Having taught Physics throughout my career, and also been a HT for 18 years, I have seen in action a possible contributory cause.

I often heard staff trying to recruit to AL tell Year 10 / 11 that they really needed separate sciences (nonsense!). When Gove pushed Triple Science my teachers supported an increase in the groups taking Triple and they often got better results. in our comprehensive school. My suggestion is that more girls took Physics, as part of their GCSEs and gained a good grade, through this route. This encouraged them to consider Physics at AL.

My experience over time is that girls will often articulate a lack of confidence in their success in Physics and so will choose other subjects where they have more confidence. Perhaps the evidence of gaining a strong GCSE grade in Physics has contributed to overcoming this understandable reluctance?

Thanks Ian, I’ve never heard that theory before and I do think it makes sense. Definitely one to ponder.