We’ve recently started work on a new project on the educational influences and labour market consequences of youth custody.

This project makes use of the phenomenal administrative data resources available to researchers in England, namely the National Pupil Database (NPD) linked to the Longitudinal Educational Outcomes (LEO) database.

The sheer size of this dataset means that we can observe a tiny subset of the population, those experiencing custody, that is too small to observe in sufficient numbers for meaningful analysis in survey data.

To identify young people who experience custody, we make use of three datasets within the NPD-LEO database:

- The National Client Caseload Information System (NCCIS), which records the activities of young people aged 16-19 as collected by local authorities

- The Children Looked After (CLA) Census, which includes details of spells in custody

- The Individualised Learner Record (ILR), which records learning aims undertaken with the Offender Learning and Skills Service (OLASS)

We plan to study the journeys and destinations of four age cohorts, those born between 1st September 1994 and 31st August 1998. Using NPD, we identified the population from these cohorts at age 15, the final year of compulsory schooling. The majority of these pupils would have completed Key Stage 4 between 2011 and 2014. There’s a lot of detail here, which for reasons of space we’ll have to leave for another day.

Having identified our population, we then calculated monthly activity indicators at academic ages 16 to 18. This includes whether we observe young people in custody in each of the three sources above.

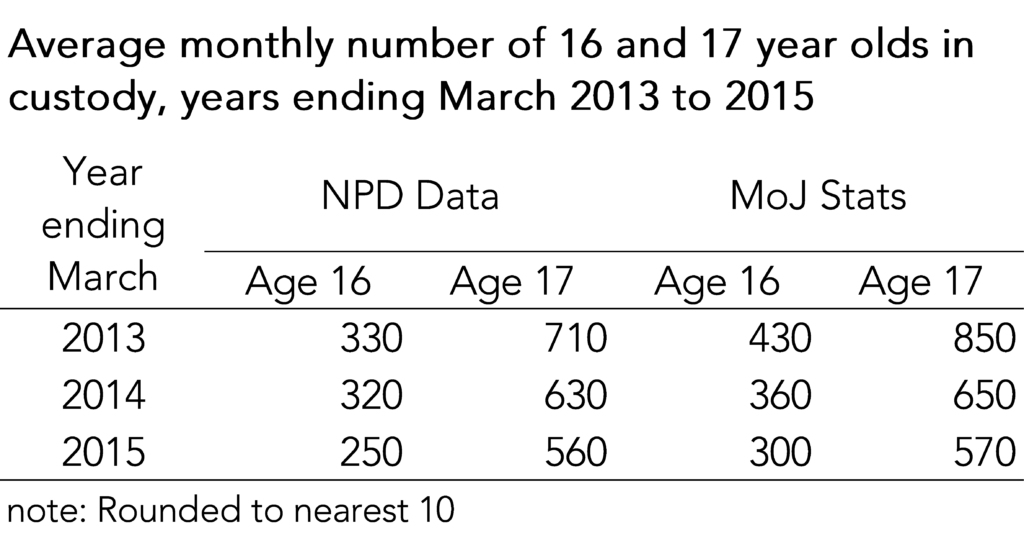

These measures of custody can be compared to published statistics from the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). So far we think we can identify young people who experience custody reasonably well although there are some gaps.

Can we identify young people in custody?

Our research concerns young people who turned 16 between September 2011 and September 2014. This was the first part of a decade in which numbers of young people in custody in the youth secure estate fell dramatically. Latest statistics show that the number of under 18s in custody fell from 1,892 in January 2011 to 527 in December 2020. It had already fallen from a high of just over 3 thousand in August 2008.

Put another way, the risk of experiencing youth custody is somewhat lower these days.

Our first task was to compare the numbers of young people we observe in custody at ages 16 and 17 to published Ministry of Justice statistics . These show the number of young people in custody by age each month, with the average monthly figure for each year ending in March also provided.

Using our NPD data, we produced statistics on as comparable a basis as possible. The main limitation is that our indicators also tell us about who was in custody at any point in a month whereas MoJ stats are based on a snapshot on a specific date in each month.

Numbers in custody at age 16 and 17 have been falling in recent years and we see this in both NPD and published MoJ stats.

On the whole, we observe fewer individuals in custody in the NPD data although differences are smaller for years ending 2014 and 2015. This is perhaps to be expected, for three reasons.

Firstly, around 4% of the cases included in the MoJ stats are young people from Wales who aren’t included in NPD data unless they happen go to school in England.

Secondly, we would also probably expect some under-recording in NPD data, particularly if a young person moves out of the local authority area where they turned 16.

Finally, the statistics calculated from NPD data do not include young people who were no longer in state-funded education by age 15 for whatever reason. We plan to return to this group later in the project.

The characteristics of those who experience custody

The statistics above show the average number of 16 and 17 year olds in custody per month. For our analysis, we look at young people who experience custody at academic ages 16 to 18 (the three years after compulsory schooling ends).

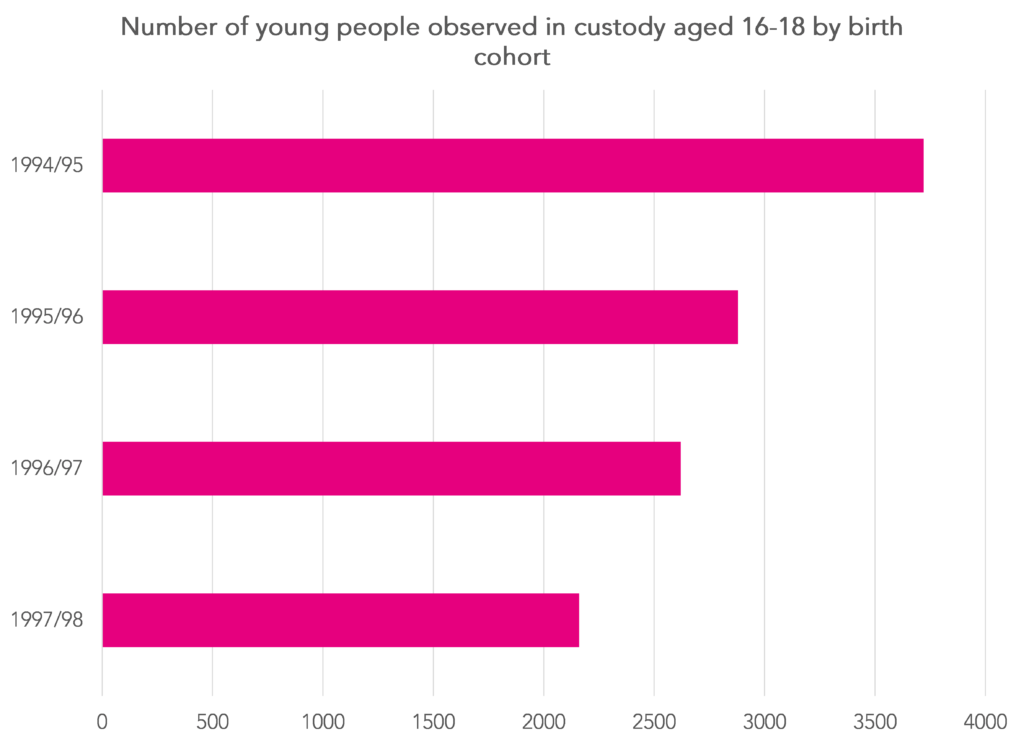

In total, across our four cohorts, we observed some 11,000 young people who spent time in custody at any point while aged 16-18 [1]. As the chart below shows, numbers among the 1994/5 birth cohort are considerably larger.

Of the 11,000, we observe around 2,000 who also spent time in custody in the years up to and including the year in which they turn 16. However, this may be an under-estimate as we only have partial data on pre-16 custody.

We can compare the characteristics of young people who spent time in custody aged 16 to 18 to those never observed in custody up to age 18. We did this across our four cohorts containing 2.5 million individuals and the following characteristics:

- Pupil attributes (gender, ethnicity, English as an additional language)

- History of free school meal (FSM) eligibility up to age 16

- History of special educational needs (SEN) up to age 16, including whether identified as having behavioural, emotional and social difficulties (BESD)

- History of exclusions (permanent and fixed-term) up to age 16

- Attendance at a Pupil Referral Unit (PRU), including alternative provision free schools

- Social care history up to age 16- whether looked after (CLA) or in need (CIN)

- Attainment by age 16 in GCSE English and maths

There are some limitations to our data. We do not observe a full history of exclusions, CIN and CLA for instance, as these datasets only started to be matched to NPD from 2006 (2009 in the case of CIN). In addition, data on SEN, FSM, ethnicity and English as an additional language (EAL) is only available for those in the state-funded sector.

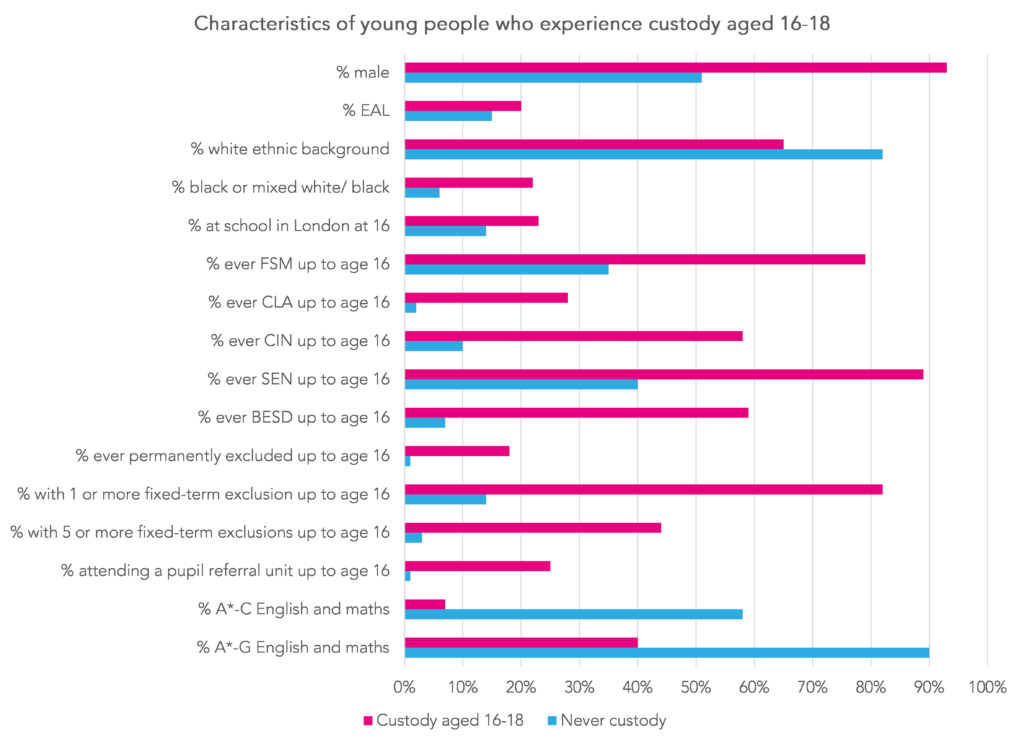

Those limitations notwithstanding, the chart below shows how the group of young people we observed in custody compare to the population who never experienced custody.

None of this will come as a surprise. Those experiencing custody were overwhelmingly male, disadvantaged and low attaining. They were also likely to have spent time on schools’ SEN registers and experienced exclusions up to age 16. Black (including mixed white/ black) young people and those ever in care or in need were also more likely to spend time in custody.

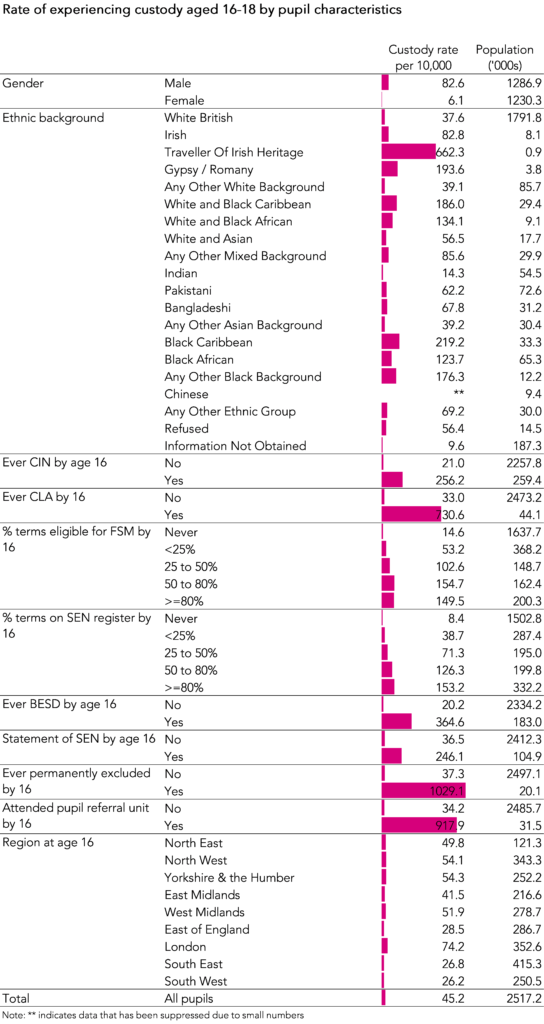

That said, it is worth re-iterating that experiencing custody aged 16 to 18 is an incredibly rare event. We observed 11,000 cases out of a total population of 2,500,000. For every 10,000 young people, 45 spent time in custody aged 16 to 18.

To finish, we also summarise rates per 10,000 for some of the characteristics shown in the previous chart. The table below largely presents the same information in a different way. Nonetheless, it shows that the pupils who experienced permanent exclusion or were placed at a pupil referral unit [2] (there is substantial overlap between these two groups) were the most likely to experience custody aged 16 to 18. Young people from a Traveller of Irish heritage background were also far more likely than those from other ethnic backgrounds to experience custody. That said, the overwhelming majority of young people from these groups did not experience custody aged 16 to 18.

So far we’ve learned that we can identify some but not all young people who experience custody in administrative data. We think this gives us a reasonable basis for the next stage of the project, where we’ll be investigating the impact of custody on post-16 study choices and early labour market outcomes.

[1] In the three years from September to August following the year in which they reach compulsory school leaving age

[2] Including alternative provision academies and free schools

This project is funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the Foundation.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment