Over the last couple of years, Key Stage 2 tests have been cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They are, however, due to come back with a vengeance in 2022 – most likely to the delight of some, but to the despair of others.

The return of the Key Stage 2 tests is likely to be met with renewed accusations that they cause children a huge amount of stress along with calls from organisations such as “More Than a Score” that they should be scrapped.

But is there really good evidence that the Key Stage 2 tests negatively affect children’s wellbeing? Actually, the existing quantitative evidence on this matter remains pretty scant.

In my new paper published today I hence undertake a thorough investigation of this issue. Using data from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) – whose English participants completed Key Stage 2 tests in 2012 – I explore how various different aspects of children’s wellbeing varies around the Key Stage 2 test date.

Importantly, because the study is UK-wide, I am able to compare results for children who live in England (where Key Stage 2 tests are conducted) to their peers who live in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales (where Key Stage 2 tests do not take place).

What does the evidence say?

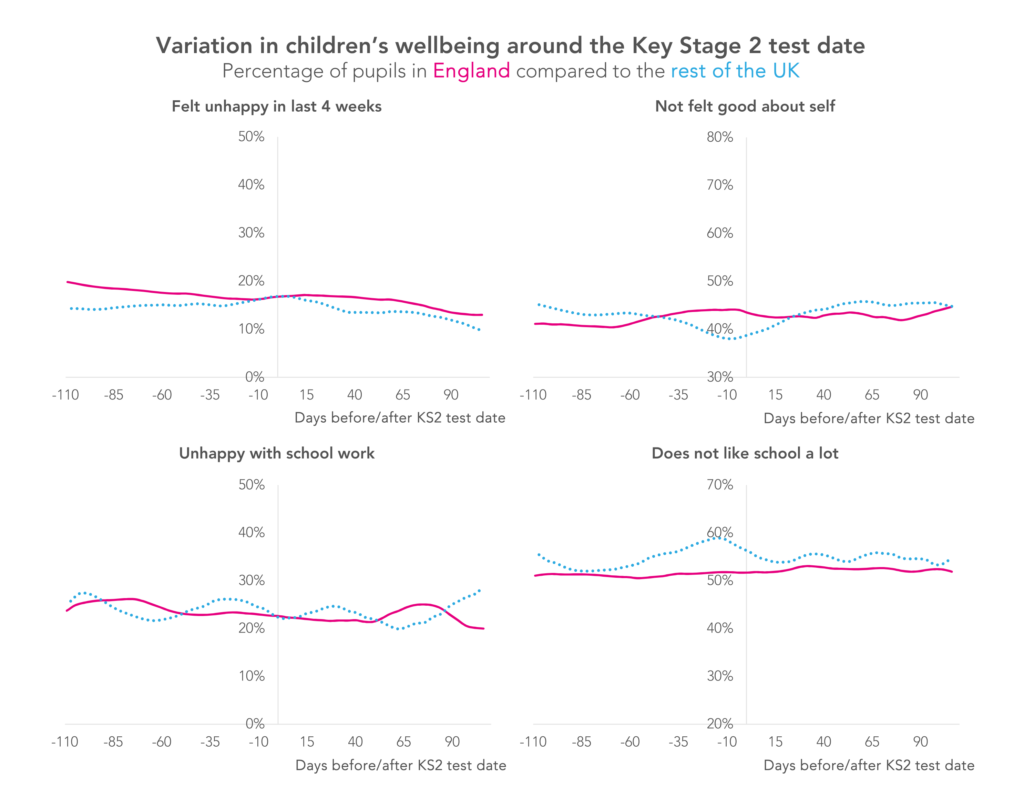

The charts above provide an overview of some of the key findings from the paper[1]. Running along the horizontal axis is the number of days the MCS survey was completed before/after the week of the Key Stage 2 tests. The vertical axis presents the percent of children who:

- Said that they felt unhappy in the last four weeks (panel a)

- Said that they do not feel good about themselves (panel b)

- Who felt unhappy with their school work (panel c)

- Who say that they do not like school a lot (panel d)

There are two key features of note.

First, the lines for England and the rest of the UK fall very close to one another, and often overlap.

Second, there is little evidence of clear variation around the time that the Key Stage 2 tests take place. There is, in other words, little sign that children in England become happier – either in general or about school specifically – once these tests are over.

Taken together, these findings provide an important counter to conventional narratives about how the Key Stage 2 tests have serious negative impacts upon children’s wellbeing. There is little sign – at least from this analysis – that this is really the case.

Conclusions?

With any accountability system, it is important that we as a society weigh up the pros and cons. While Key Stage 2 tests may provide valuable information about the academic achievement of schools and their pupils, it has been claimed that this also leads to a narrowing of the primary curriculum and negatively impacts upon the wellbeing of both pupils and teaching staff.

Unfortunately, despite the rhetoric, we currently have only a limited understanding of this trade-off.

What this blog has illustrated, however, is that concerns about a negative link between the Key Stage 2 tests and children’s wellbeing may – on the whole – be somewhat overblown.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Surely a “thorough investigation of this issue” would involve collecting new data to explicitly explore the issue?

Currently, this seems to be considered through data that happens to be available as part of an existing survey – it’s not able to clearly cover potential ’cause and effect’ e.g. surveying and interviewing students before and after the tests – nor does it consider students’ views about well-being in the context of testing and suchlike.

It’s easiest to use available data and try to make inferences… but is it the best way to undertake research?

Complex statistics and existing data can only do so far.

We can’t dodge the issue for ever… We need to actually ask students about their lives. Otherwise, are we really valuing their wellbeing and experiences?

An important aspect of the KS2 tests, which limits the adverse impact of these tests on children’s wellbeing, is that they are low-stakes tests from the point of view of the child. Of course, they are high-stakes tests for the school, and it’s possible that teachers may transmit some of their preoccupation onto children. But this analysis suggests that there’s no evidence of that happening, or at least not in a way that children find too hard to handle. That’s a credit to teachers.

11+ tests are another matter: it would be interesting to do a similar study comparing children in 11+ and non 11+ areas.

It might be interesting to look at outcomes achieved in Summer 2020 where previous SATS papers were used by schools (I suspect many) to support TA judgments for secondary transition. Although not done in truly stark exam conditions these will have been conducted under test conditions and given that they were sat much later in the term it gave nigh on two months ‘additional’ learning time (agreed not additional due to time out of school. Certainly from our perspective the anxiety levels of staff and pupils was reduced resulting in a more positive experience. I agree with the above comment that year on year staff do their utmost to shield pupils from any increase in anxiety making it difficult to measure. Teacher marked SATS showed no bias within our school and marking was moderated (albeit internally). Given the effect that SATS have on curriculum time especially in Year 6 a move to teacher marked papers in July could provide a route that supports accountability, maintains wellbeing and means that Year 6 is truly a whole year of learning. There would be inevitable concerns about workload but I imagine most Year 6 staff will say that marking past papers is part and parcel of the year and they are marked as a matter of course – the trade off might perhaps be a positive one.