Ayana is part of a team based at the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health at UCL using the ECHILD database, which links health and education data in England, to better understand how education affects children’s health, and how health affects children’s education. They will be publishing key insights on the Datalab blog over the course of their research.

Children with conditions such as learning disability, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), cerebral palsy, and Down syndrome can be said to have a ‘neurodisability’. They make up 3.8% of the primary school population in England and are a key research focus as they have complex health needs and are likely to struggle in school.

Unfortunately, the educational outcomes of these children are understudied. There is little evidence on the collective outcomes of children with neurodisability or their progression in attainment throughout primary school.

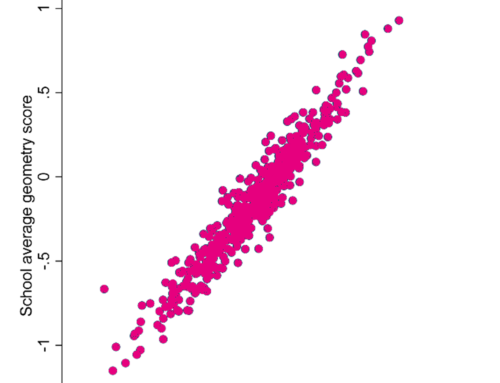

We are currently focused on investigating the progression of educational outcomes across primary school for children with and without neurodisability in England to see if differences between them narrow or widen with time. However, the results make it clear that we cannot compare the differences in attainment across time without considering who is sitting these exams.

Data

We use the Education and Child Health Data from Linked Data (ECHILD) database, which links educational and health records across England.

We track five cohorts of primary school children who have reached the end of Year 6 between 2014/15 and 2018/19. We track them from the Spring census of Reception (i.e. from 2008/9 to 2012/13). These children were born in NHS hospitals between 1st September 2003 and 31st August 2008.

We then observe pupils’ outcomes at the end of reception (Early Years Foundation Stage Profile; EYFSP), the end of Year 2 (Key Stage 1), and at the end of Year 6 (Key Stage 2). We also look at the number of children with and without neurodisability who appear in the school census during the term of assessment, but do not sit the exams.

Method

We compared the proportion of children with and without neurodisability who did not achieve the national expected level in English and Maths assessments for EYFSP, Key Stage 1, and Key Stage 2. We also compared the proportion of children who did not sit each exam.

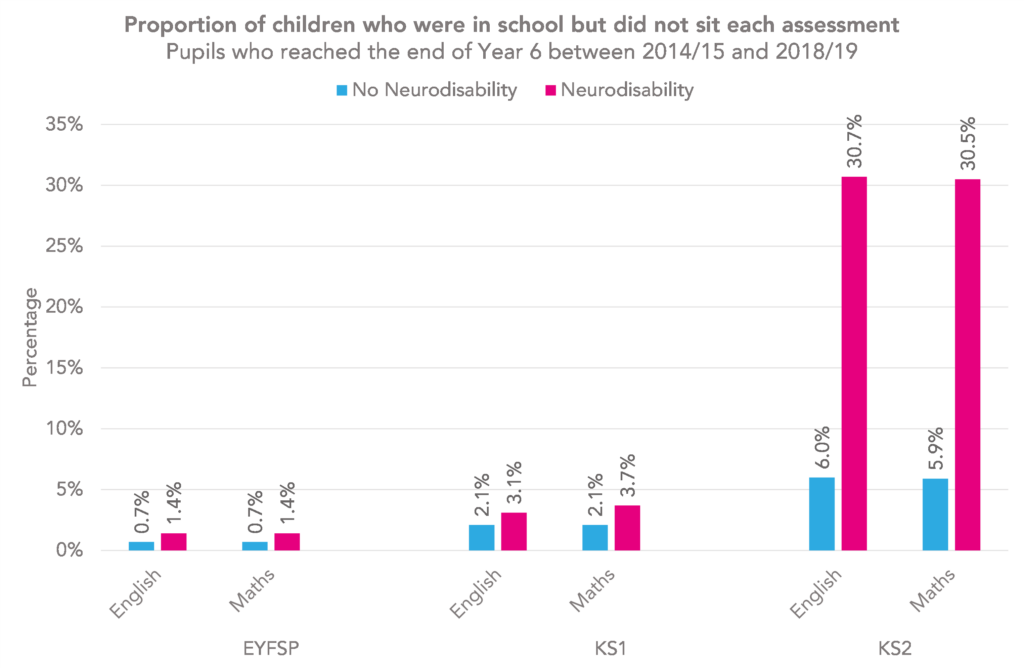

In the early years of primary school, less than 4% of children with neurodisability did not sit exams. However, by Year 6, nearly a third of these children did not sit exams despite being in school.

So, while children with neurodisability generally participate in school assessments alongside their peers during EYFSP and Key Stage 1, the transition to Key Stage 2 results in a substantial proportion of children with neurodisability not participating.

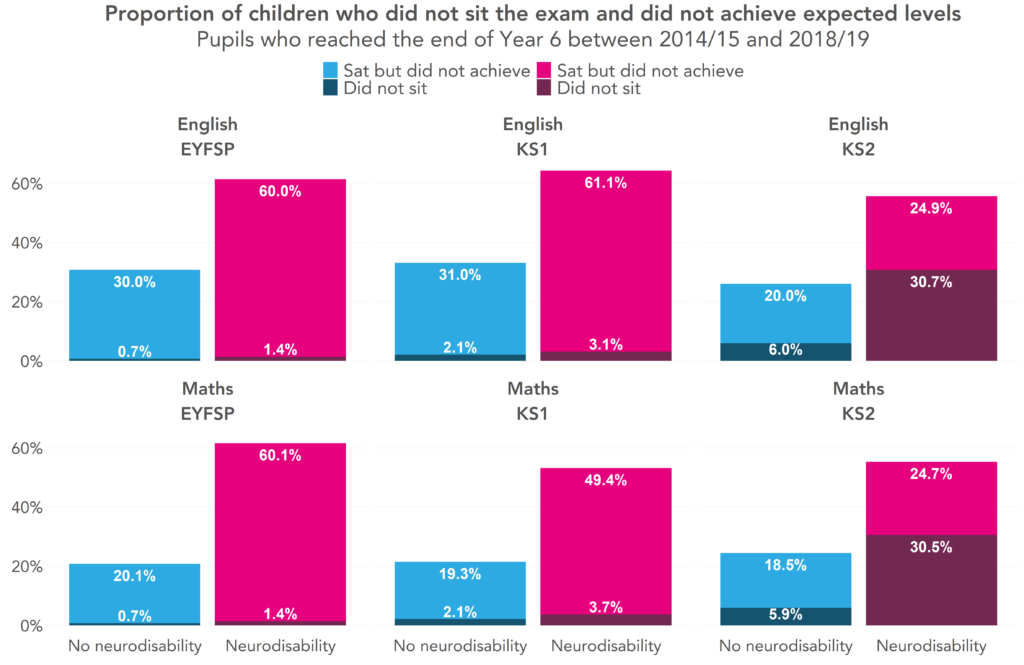

When we consider the children who do not sit the exam with the children who do not achieve the expected levels, we see that the differences in attainment outcomes increase over time.

Describing comparisons of attainment that are restricted to those who take the test could be misleading. To check the robustness of the finding, we should count all children in school in the denominator, including those who did not sit the test. This is especially important when comparing groups who are likely to be excluded from testing because of learning difficulties, behaviour problems or frequent absence.

The substantial increase in the proportion of children who do not sit these exams from Year 2 to Year 6 highlights a critical period where exams may become too challenging, or adequate support is lacking, causing many children with neurodisability to be excluded from assessments. SEN provision should focus on this stage of primary school to ensure these children receive the necessary support to participate fully.

A full description of our ongoing study can be found here.

The EYFS isn’t an exam, but teacher assessment of ability conducted over time. The data collected at KS1 was teacher assessment, partly based on tests, but wouldn’t exclude pupils that hadn’t sat the test. Whereas the KS2 outcomes you’re looking at in reading and maths are based on the test. Many of these pupils will have been given a teacher assessment if they were unable to take the test. I am not sure you are comparing like with like here.

Hi Jo, thank you for your comment, you raise extremely important point that the content of the tests and thresholds for sitting them differ and differences over time need to be interpreted with caution. Our findings highlight that comparing attainment solely among those who take the test can be misleading. We suggest a sensitivity analysis that includes all children enrolled in school in the denominator. We recognise the need for the National Pupil Dataset to capture other information, such as teacher assessments on the progress of children with neurodisability.

Hi Anya – very interesting, thank you for your research. I have a few questions:

1. Are there any plans to follow up those children who didn’t sit exams yet were not diagnosed with neurodisability. I ask this because many children are not diagnosed until adolescence.

2. Do you have a breakdown of figures by neurodisability ie what proportion of children with ADHD, autism, neurological disorders and genetic disorders etc weren’t able to take their exams at what stage? was there more consistency of inability to sit tests around one age group than another?

3. Do you have any plans to find out what prevented children (again broken down by neurodisability)?

A lot of questions I know, but that’s what interesting research provokes!

Best regards

Tim

Hi Tim, thank you for your insightful questions and your interest in our research.

This specific project will only focus on primary school children. However, within our wider study group (The HOPE Study), a short 18 months study will start soon will extend this research question to secondary school and post-16s.

We will show a detailed breakdown of outcomes by specific conditions in the coming months.

We will not be looking into what prevented children, but this is a good question that would benefit from mixed methods research that includes qualitative methods involving children and their parents.

Thank you, as an educationalist and lead in neurodivergence and physical health challenges and other advocacy in ND attainment and attendance following our published peer reviewed paper last year, we are very pleased to see this curiosity and post on cyp nd health, from SEDSConnective.org We would be happy to help in anyway

Hi Jane,

Thank you for your comment. We are pleased to hear that you are interested in our research and will be sure to reach out to your organisation with any questions or advice that we may need.

Great to see attention being paid to this group. But my experience in mainstream and special education suggests that the *roots* of this division lie much earlier: like many challenges, the impacts are cumulative over time. If we can support greater effective inclusion from pre-school onwards, then it seems likely we can head off, or at least postpone further, some of these exclusions from normal school life (and we have to remember that exclusion from taking assessments is likely to be based on the child having experienced significant trauma leading up to the test period, so that they are unable to participate). Exclusion from assessments is a symptom of what is going wrong for these vulnerable children, rather than a core problem in itself.