It’s a bit of an understatement to say that the pandemic brought some disruption to education. Aside from many other things, it led to the cancellation of public exams in 2020 and 2021, and grades being awarded through CAGs and TAGs respectively. And, of course, we saw an increase in top grades at GCSE in both years, as well as in 2022 when grade boundaries were adjusted to avoid too sharp a fall in grading.

But what happened to the gender gap in grading during this period, and how did that vary by subject? I’ll be investigating here.

Data

I’ll be using data from the KS4 exam and pupil tables from the National Pupil Database from 2018-23. I will focus on the gender gap in the proportion of pupils achieving a grade 7 or above at GCSE.

I include several grouped subjects, defined as follows:

- Art and design subjects: art and design, art and design (3d studies), art and design (critical studies), art and design (fine art), art and design (graphics), art and design (photography), art and design (textiles)

- Classical subjects: ancient history, classical civilisation, classical Greek, Latin, other classical languages

- Design and technology subjects: D&T electronic products, D&T engineering, D&T food technology, D&T graphic products, D&T product design, D&T resistant materials, D&T systems & control, D&T textiles technology, design & technology

- Other modern languages: Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, Dutch, Gujarati, Italian, Japanese, Modern Greek, Modern Hebrew, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Russian, Turkish, Urdu

An overview of the gender gap

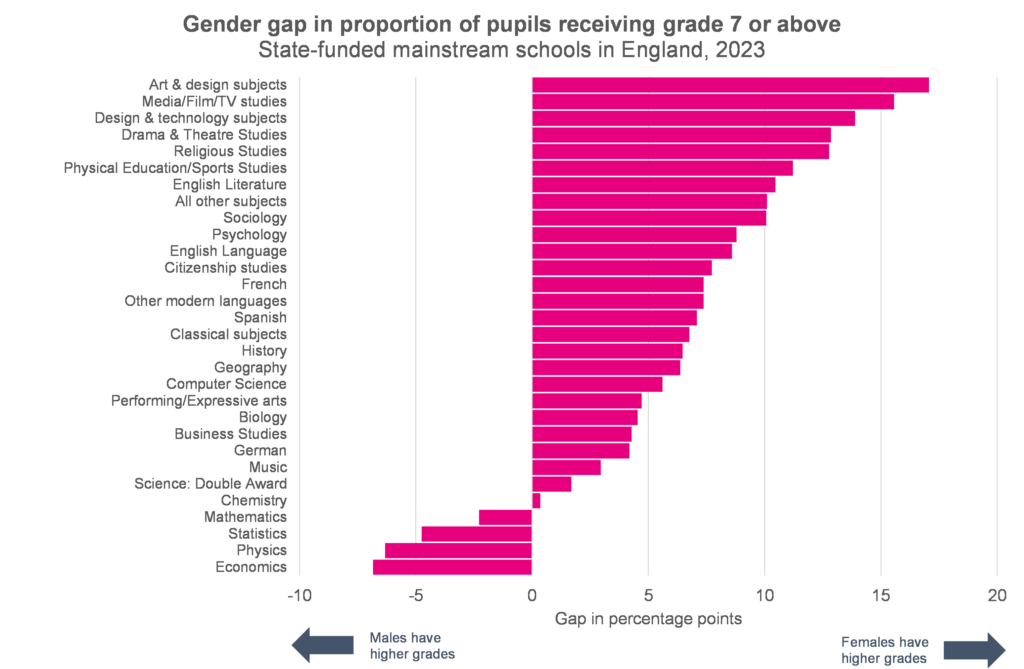

Let’s start with a look at the gender gap in top grades in 2023, broken down by subject.

Some subjects – including music, double award science, chemistry and maths, have very small gender gaps. In some – statistics, physics, maths and economics – the gap is negative, that is, male pupils achieved higher grades than female pupils. In the majority of subjects, the gap is positive – that is, female pupils achieved higher grades than male pupils. But there’s quite a lot of variation in the size of the difference, and some subjects – most notably art and design, film/media/TV studies, and design and technology – had very large gaps.

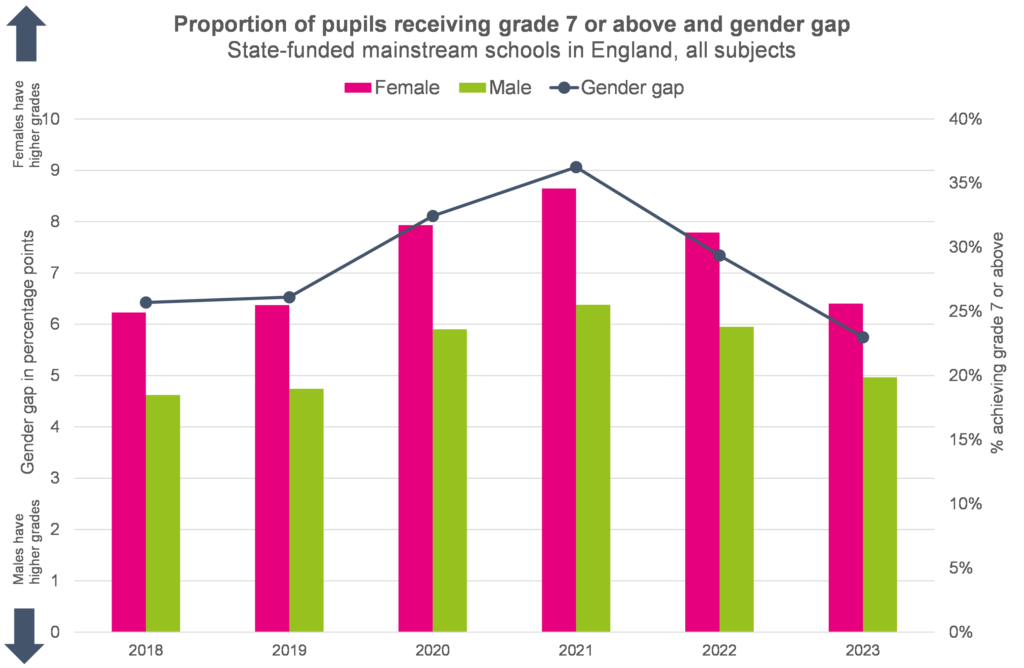

Now let’s see how the overall gender gap in top grades has changed over the last few years. The chart below shows the gender gap as a line plotted against the primary (left) axis, and the proportion of male and female pupils achieving top grades as bars plotted against the secondary (right) axis.

During the pandemic the gender gap increased. This coincides with grades being awarded via CAGs and TAGs in 2020 and 2021 respectively, and the adjustments to grading made in 2022. During this period, both male and female pupils were more likely to achieve top grades than pre-pandemic, but the increase was sharper for female pupils, hence the widening of the gap. By 2023, the gap had fallen back to slightly below the pre-pandemic level.

It’s interesting to speculate on why the gap increased. It may be that CAGs and TAGs introduced a slight bias in favour of female pupils, but that doesn’t explain why the gap remained higher than pre-pandemic in 2022. It’s possible that female pupils were more likely than male pupils to be working at the threshold between a grade 6 and grade 7, and so the adjustments to grade boundaries were more likely to push female pupils up to a grade 7.

But this is just speculation. Let’s turn to some actual data.

The gap by subject

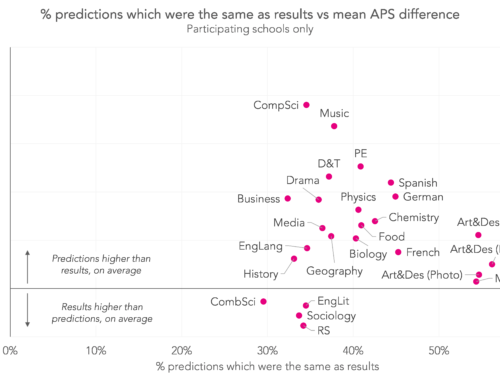

We’re going to look at whether the change in the gender gap was consistent across subjects. The chart below allows you to select a subject of interest.

Most subjects roughly follow the same pattern that we saw across all subjects: a higher gap in favour of female pupils during 2020-22, with a peak in 2021, before a fall back to roughly pre-pandemic levels in 2023. But in some subjects, we see quite a different pattern.

In Spanish, German and music, the peak comes in 2020 rather than in 2021, and in other modern foreign languages the gap was actually lower in 2020 than pre-pandemic. The different pattern for other modern languages is probably connected to the large fall in entries to this group of subjects during the pandemic.

Psychology saw a peak in 2022 rather than 2021, as did performing/expressive arts. In classical subjects, the gender gap was lower in both 2020 and 2022 than pre-pandemic, and in statistics the gap increased in favour of male pupils just before the pandemic, and has remained roughly consistent since.

Subjects with particularly extreme peaks during 2020 and 2021 include computer science, economics and physical education / sports studies.

The gap in some subjects did not return to pre-pandemic in 2023. Computer science, D&T and art and design subjects were among those with a larger gender gap in favour of female students in 2023 than in 2019, and statistics and economics both had a larger gender gap in favour of male students.

Disadvantaged pupils

Now let’s see if the gender gap looks different for disadvantaged pupils.

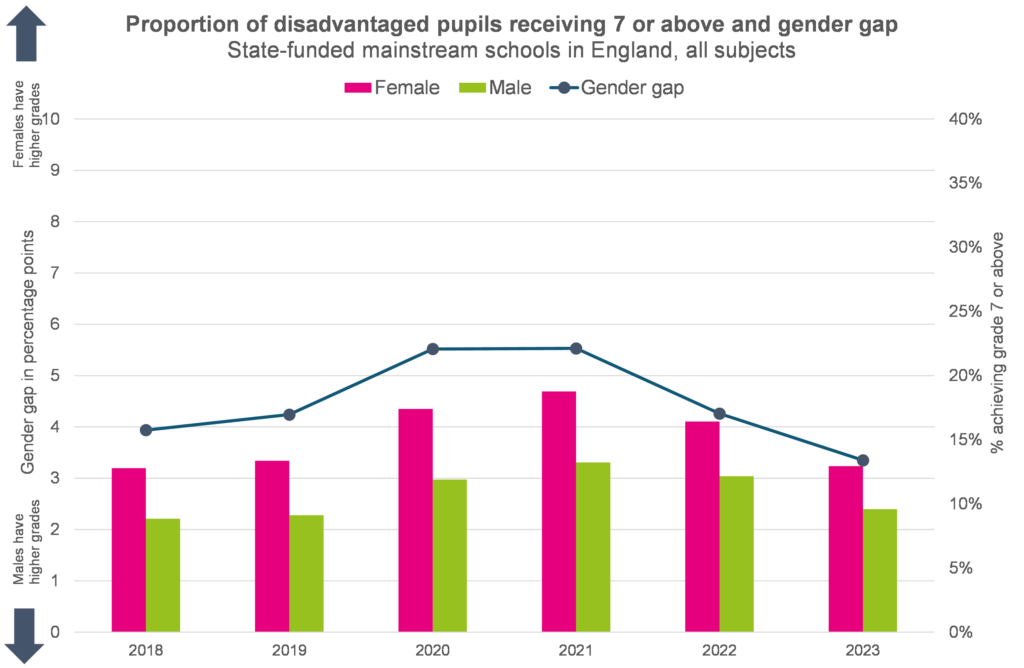

We’ll start with a look at the overall pattern for disadvantaged male and female pupils.

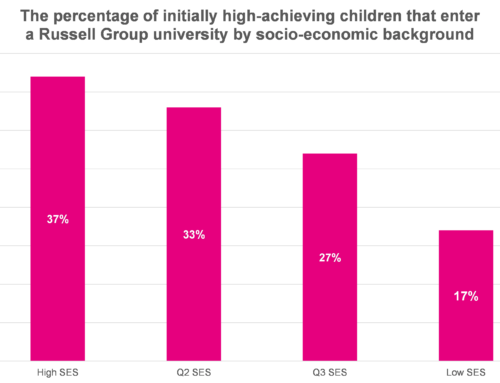

Again, grades for both male and female students increased during the pandemic, as did the gender gap. One thing to note is that grades for disadvantaged pupils tend to be lower than for their peers; the disadvantage gap is far bigger than the gender gap. In 2023, 13% of GCSEs taken by female disadvantaged pupils were graded 7 or above, compared to 26% of those taken by female pupils not identified as disadvantaged. For male pupils, the figures are 10% and 20%.

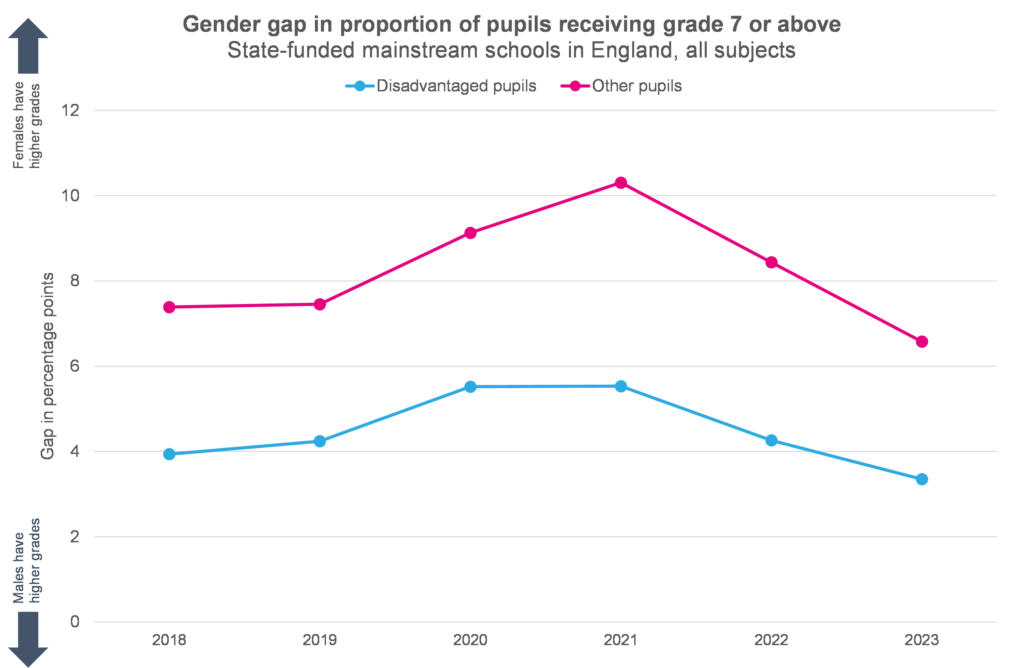

The next chart shows how the gender gap compares.

The pattern over the last few years is similar, but with a couple of interesting differences. Among disadvantaged pupils, there was very little difference in the gender gap between 2020 and 2021, whereas for their peers there was a peak in 2021. And for disadvantaged pupils, the gender gap was back to pre-pandemic levels by 2022, but for their peers it remained above until 2023.

A brief aside

We’ll look in a moment at how the gender gap for disadvantaged pupils breaks down by subject, but first a brief detour to acknowledge something I found surprising. I had expected the gender gap to be higher for disadvantaged pupils, but I actually found the opposite.

I must admit I don’t think I had based that expectation on anything particularly solid. But I still think this is interesting and plan a future blog looking at the interaction between gender and disadvantage gaps at GCSE in more detail.

One current theory is that perhaps non-disadvantaged pupils are more likely to be clustered around the 6/7 grade boundary than their disadvantaged peers. If so, then a small difference in attainment between non-disadvantaged girls and boys might translate into a big gender gap in the proportion achieved grades of 7 and above, because it would push lots of girls over the grade 7 threshold.

The gap for disadvantaged pupils by subject

Let’s get back to our subject-by-subject breakdown. The chart below shows how the gender gap has changed over time for disadvantaged pupils for a particular subject. Note that, due to small numbers, data on performing / expressive arts is not included here.

Here we see much less consistency between subjects than we did when looking at all pupils. In some subjects, including English literature, biology, French and Spanish, we see the biggest gender gap in 2020. In others, including maths, computer science, history and geography, we see a peak in the gap in 2021.

Some of this volatility is likely because of the lower numbers involved when we look at disadvantaged pupils rather than all pupils, particularly in subjects with lower entries numbers and / or a lower proportion of entries from disadvantaged pupils. But some of it may be because CAGs and TAGs affected the grading of disadvantaged male and female pupils differently to their peers.

Summing up

The gender gap in top GCSE grades widened during the pandemic, peaking in 2021. This was reasonably consistent between subjects, but some – including computer science, economics, and sport studies – saw particularly extreme peaks, and others – including German, Spanish and psychology – saw a different pattern.

For disadvantaged pupils, the gender gap also widened during the pandemic, but there was much less consistency between subjects, with peaks in some subjects occurring in 2020 under CAGs, and others in 2021 under TAGs.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment