Cast your mind back to Summer 2020.

The first summer of the pandemic. Festivals and sporting events were cancelled. Grant Shapps had to quarantine after his holiday. The Turkey Twizzler made a surprise comeback.

And exam results were in the news on a daily basis.

In this blogpost, we look back to that Summer and find out what effect higher GCSE grades had on school staying on rates.

Data

In 2020, 69% of students attending state-funded mainstream schools in England achieved the equivalent of 5 or more GCSEs at grades 9-4 including GCSE English and GCSE maths. This figure stood at 59% the previous two years.

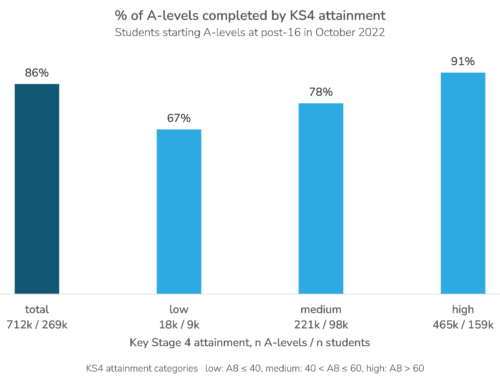

This indicator used to be considered a rough threshold for progression to A-level (and equivalent) study. Given that school sixth forms largely offer provision at this level, we might have expected the rise in grades to lead to an increase in the size of school sixth forms.

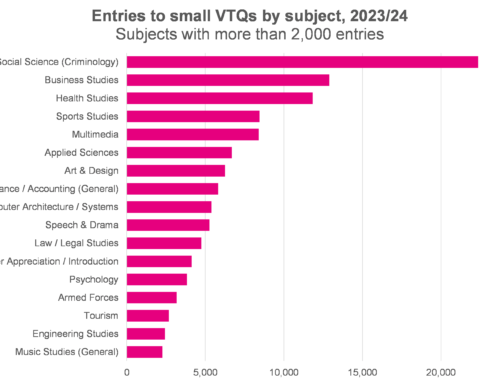

At this point, it’s worth noting that not all schools have sixth forms. And not all students who want to study A-level and other equivalent qualifications want to do so at their school. Over half of young people go to Colleges at 16. At this stage we don’t have any data on College enrolments in 2020/21 hence we present only a partial picture about what happened in schools.

We link data on students who completed Key Stage 4 in 2020 (and previous years) in state-funded mainstream schools to the School Census in the following January. This tells us who stayed on at a school.

In total, 217,000 students stayed on in 2020. This was an increase of almost 17,000 on the previous year. However, the total cohort was also larger (551,000 in 2020 compared to 534,000 in 2019). Expressed as percentages, 39.3% of the cohort stayed on in 2020 compared to 37.5% the previous year. Higher, but not much higher.

Of those who stayed on in 2020, 90% had achieved 5 or more A*-C grades including English and maths compared to 85% the previous year. The average GCSE grade also increased by a third of a grade to 6.01.

Schools with Sixth Forms

For the remainder of this article, I restrict the analysis to pupils who complete Key Stage 4 at schools with sixth forms.

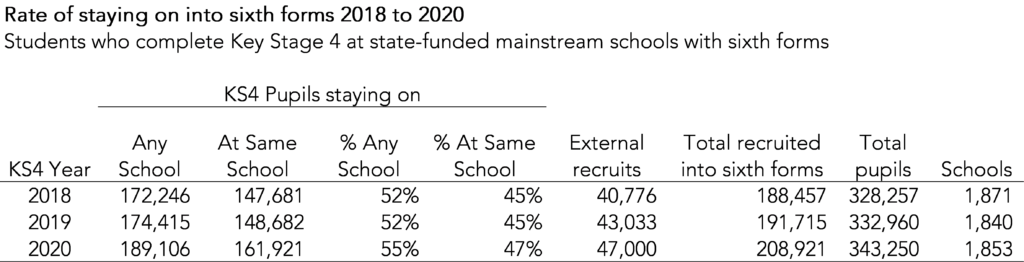

In the table below, we show the numbers of students at these schools who stay on into the sixth form. The “any school” columns mean going to any school sixth form (including those which only cover the 16-19 age range) and the “same school” columns mean staying on at the same school.

Overall we see that 55% of students who completed Key Stage 4 at a state-funded mainstream school with a sixth form in 2020 were enrolled in schools the following January. 47% stayed on at the same school. These figures will include students who may be repeating Year 11 or studying GCSE-level courses as well as those taking A-levels and equivalent qualifications.

At almost 40% of schools, the number of students recruited into the sixth form changed by no more than 9 pupils. However, 27% of sixth forms increased their intake by 20 or more students compared to 2019.

The sixth forms are of different sizes so instead of looking at change in student numbers, let’s use the percentage increase in numbers between 2019 and 2020.

And let’s also consider the minimum entry requirement for each sixth form. Leaving aside students who appear to be resitting Year 11, I use the GCSE average point score of students at the 10th percentile of their school. Both measures are plotted on the heatmap below.

The heatmap suggests that schools tended to increase their sixth forms slightly but also raised their minimum entry requirement (MER). There was also a (relatively) small number of schools which increased in size while maintaining their MER. And indeed some schools that shrunk in size or reduced their MER.

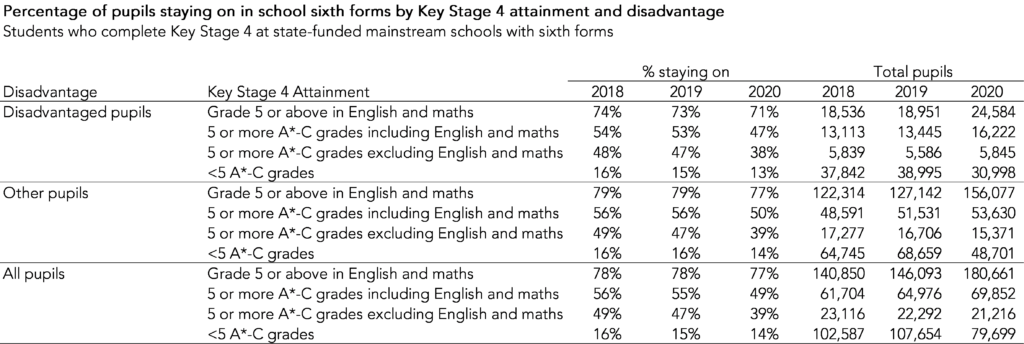

To finish off, let’s look at the rate of staying on (in any school) by Key Stage 4 attainment and disadvantage. I’ve used a broad hierarchical classification for Key Stage 4 attainment.

The staying on rate among students who had achieved grade 5 in English and maths fell only slightly (from 78% to 77%) in 2020. However, more students had achieved this standard in 2020. So converting the percentages into numbers of students, this represents an increase of 24,000 students staying on.

Among students who hadn’t achieved grade 5 in both English and maths but had achieved at least grade 4 in both of them plus 3 other GCSEs (or equivalent), the percentage staying on fell from 55% to 49%.

So this brings me back to the original question. It’s clear that sixth forms have tended to grow in size following the awarding of CAGs. Some of this was to be expected: the 2020 cohort was larger than the previous cohort.

But the staying on rate of students with 5 or more 9-4 grades (or equivalent) at GCSE including English and maths fell.

This begs further questions, none of which I have answers to at the moment.

Why didn’t more of these students stay on?

Were schools limited in how many extra students they could take on?

And what did these students go on to do at College?

- In most subjects, GCSE results increased by between a third and a half of a grade in 2020

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Very interesting analysis.

Is it possible that there was a difference in the increase in GCSE average grades between schools with 6th Forms and those without?

It would have been quite late for schools with 6th Forms to radically alter their MER for September 2020 entry when exams were cancelled in Spring 2020. Schools with 6th Forms would have been aware that significant grade inflation would have led to students starting A-level courses for which they would not normally have reached the entry requirements.

Thanks Jon. From memory I don’t think there was much difference (on average) between schools with sixth forms and schools without but I ought to double check as its a good point.

Interesting analysis. My guess is that school Sixth Forms are more likely to nudge less performing students towards colleges. They may be doing this through advice & informal influences or by raising their entrance requirements for A-Levels. FE colleges, in particular, are much more interested in recruitment numbers. It’s the market influences affecting the data.

Thanks Tom. I had wondered how much advice and guidance schools were able to give in 2020 following lockdown.

The analysis of the question caused irritation: what is the purpose to attempt an answer with omission of further education colleges and apprenticeships??? Perhaps the blog post was an attempt to demonstrate access to some data, to sell for prospective schools…

Couple of reasons. The first is pragmatic: we don’t have data on Year 12 college enrolments (from the ILR) available for analysis in the way we have data on school enrolments available. The second is that we’re specifically looking at what happened in school sixth forms (most of which awarded GCSE grades to their students in the previous year). I agree there is a piece of work to be done examining what the impact of CAGs and TAGs was on FE.

I can’t speak for other areas, but we had a new sixth form college open a few years ago. This has led to several schools that had small sixth forms – offering a limited number of A levels with the fairly poor outcomes that you would expect – either closing their sixth form completely or focusing on non-A level courses. One large college can offer a much broader range of courses and specialised teaching provision than half a dozen small school sixth forms. So we’ve seen a big drop in the number of students in school sixth forms, but a slight increase in the number of students taking A levels, and a big increase in the number of students achieving good A levels.