For once the title question I’ve chosen for this blogpost is one that I can actually answer. The answer is yes.

That was a short post.

But, alas, I’m not really letting you get away just yet. There’s plenty more to say on the subject.

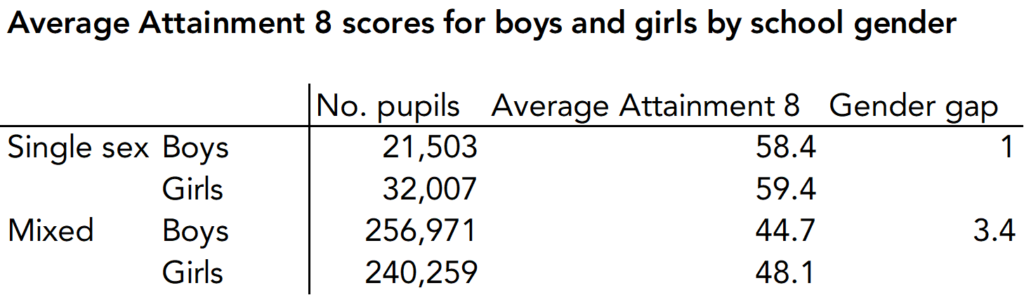

Pupils in single sex schools do indeed get better grades, on average, than those in mixed schools – the average Attainment 8 score for pupils in state-funded single sex schools was 59.0 last year, compared to 46.3 for pupils in mixed schools.

But the interesting question is: why? Is it because the single sex environment is a better one for learning? Or is it because of the many other differences between single sex and mixed schools?

Data

I used data from the National Pupil Database to identify pupils who attended mixed and single sex schools, based on the school that pupils were attending when they completed Key Stage 4. I looked at the cohort of pupils who completed Key Stage 4 last year.

I will be talking about gender of pupils as opposed to sex. I’ve done this because the National Pupil Database includes a measure of gender but no measure of sex. The gender measure currently includes two categories: male and female, which I’ll be using throughout.

The data analysed includes all pupils who attended a state-funded mainstream school and for whom data on pupil characteristics and prior attainment at KS2 was available. This excludes any pupils who did not complete KS2 in a state-funded school in England.

Some background

I’m sure it’s no surprise to most readers that single sex schools tend to be quite different from most mixed schools in terms of pupil and school characteristics. But let’s take a look at just how different they are.

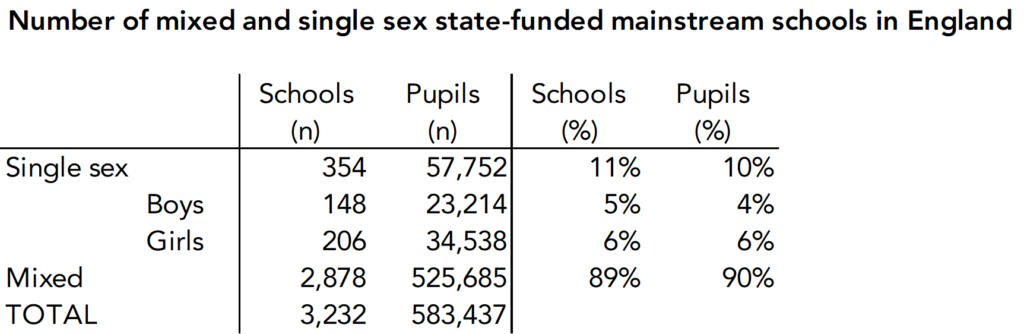

We’ll start with a look at how many state-funded single sex secondary schools there are in England.

Attending a single sex school is unusual: around 90% of pupils in state-funded schools completed Key Stage 4 in a mixed school last year.

But it is more common in some areas than others. In London, nearly a quarter (24%) of pupils attended a single sex school, while in the North East, just 3% did so. It’s also more common for girls than for boys: there are over 10,000 more girls than boys in single sex schools.

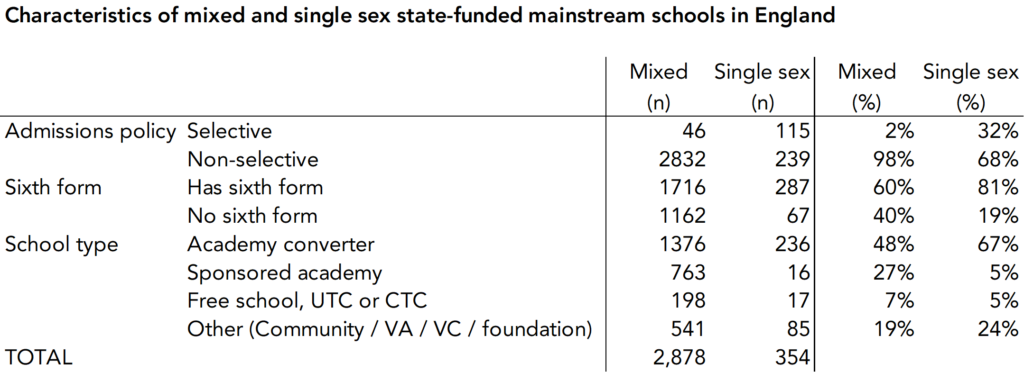

And there are plenty of other differences in terms of school characteristics, as shown below.

Around a third of single sex schools are selective (grammar) schools, compared with 2% of mixed schools. They are far more likely to have a sixth form than mixed schools, and, unlike mixed schools, most are academy converters.

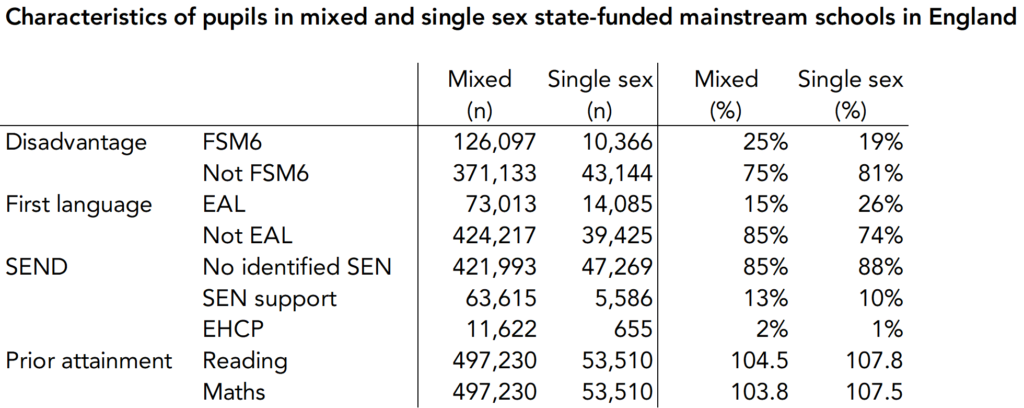

Given these differences in school characteristics, we’d expect some large differences in pupil characteristics too, and that’s exactly what we see. And just to note that from this point onwards I will be using a slightly reduced dataset, which excludes pupils for whom data on pupil characteristics and prior attainment at KS2 was unavailable in the National Pupil Database.

Pupils in single sex schools were less likely to be disadvantaged or to have an identified SEN, more likely have English as an additional language and had higher average levels of prior attainment in both maths and reading.

Controlling for the differences

Given all of the differences in school and pupil characteristics, it’s not surprising that single sex schools have higher attainment: they’re more likely to be selective, to be located in London (where grades tend to be higher), and to have an intake of pupils with low levels of disadvantage and SEN and high levels of EAL and prior attainment.

So it may be that these differences explain all of the differences in attainment.

To try and understand more about how much impact single sex schooling actually has, I’m going to identify a group of mixed schools that have similar school and pupil characteristics to single sex schools. If pupils in single sex schools still do better than pupils in the similar mixed schools, it’s much more likely that the difference is because of the same sex environment – although we shouldn’t forget that it might be caused by other unobserved differences.

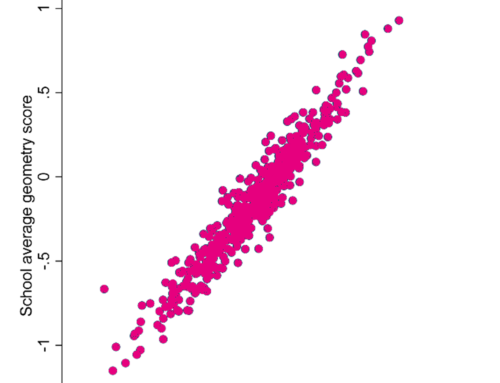

To do this, I matched each of the single sex schools included in this analysis to a similar mixed school based on propensity scores. [1] I then fitted regression models to compare the attainment of pupils in the single sex schools to that of pupils in the similar mixed schools, controlling again for differences in pupil characteristics.[2]

The scores on the doors

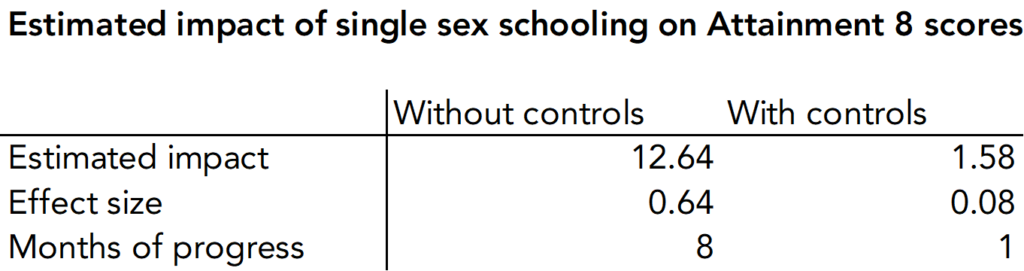

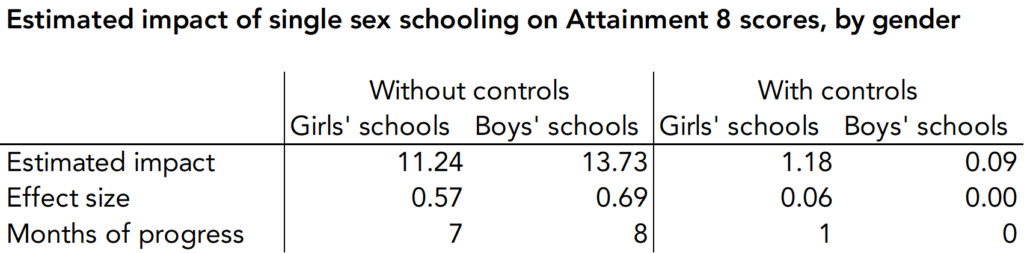

The results of this analysis are shown in the table below.

As I mentioned at the start of this piece, there’s a big difference in Attainment 8 scores for pupils in state-funded single sex schools – 12.7 points. This works out to be the equivalent of eight months of progress, if we use the Education Endowment Foundation’s methodology.

But when we compare to similar pupils in similar schools, the difference falls to just 1.6, or one month of progress.

So, the differences in pupil and school characteristics explain around 90% of the difference in attainment. But not quite all of it.

Is the impact of single sex schooling greater for girls?

What about differences in impact by gender? Previous work has suggested that single sex schooling may make more of a difference for girls than for boys.

Let’s start by looking at the difference in attainment before any controls are applied.

In both mixed and single sex schools, girls’ attainment is, on average, higher than boys’. But the gender gap in attainment is smaller among pupils in single sex schools. This might seem to suggest that single sex schooling is more beneficial for boys than it is for girls, but a look at some of the differences in school and pupil characteristics of boys’ and girls’ schools tells a different story.

While both girls’ and boys’ schools are noticeably different in profile to mixed schools, they are also different from one another. A higher proportion of boys’ schools than girls’ schools are selective, they are slightly more likely to have a sixth form, and they have a lower proportion of disadvantaged pupils. And there are also differences in prior attainment at KS2.

This looks like a job for some more matching and modelling.

I repeated the analysis to compare girls in girls’ schools to girls in similar mixed schools, and boys in boys’ schools to boys in similar mixed schools.

Before controlling, there is quite a sizeable difference in Attainment 8 scores for both boys and girls in single sex schools compared to their peers in mixed schools. And the difference is larger for boys.

But once we control for differences in school and pupil characteristics, the estimated impact of single sex schooling is greatly reduced; for boys, it is virtually zero. And for girls, around 90% of the difference in attainment is explained by differences in school and pupil characteristics.

Summing up

We’ve seen that pupils in single sex schools do indeed get higher grades than their peers in mixed schools, especially boys. But we’ve also seen that the vast majority of that difference can be explained by looking at differences in school and pupil characteristics.

For girls’ schools, a small difference in attainment does remain even after controlling for these differences: the equivalent of around one month of progress if we used the EEF’s terminology, or around one tenth of a grade in each of the subjects that make up Attainment 8.

For boys’ schools, there doesn’t seem to be much of a difference in attainment at all once we account for differences in school and pupil characteristics.

But, as ever, we would sound a note of caution: the analysis we’ve done here only controls for differences that we can observe in the data. It may be that there are other differences between mixed and single sex schools that we’ve not picked up on here – and if we were to pick up on them, we might come to a different conclusion.

Bottom line: based on this analysis, single sex schooling may provide a modest boost to grades for female pupils, but doesn’t seem to make any difference for male pupils.

[1]: Schools were similar with respect to: school type, region, average KS2 reading and maths scores, % FSM6 pupils, % EAL pupils, whether or not a school is selective and whether or not a school has a sixth form. I also excluded mixed schools with an unusually high proportion of male or female pupils (greater than or equal to 60%) from the matching pool.

[2]: Controls included: KS2 reading score, KS2 maths score, ethnicity, SEN status, FSM6, EAL, school average KS2 reading score, school average KS2 maths score, % FSM6 in school, % EAL in school, % female pupils in school.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Thank you for the work you’ve done on this – having attended a single-sex school in the 70s-80s, it was fascinating to read.

On a less grand scale, we also analyse and look for possible barriers to academic success each year, we do look at the summer born effect, which I feel has been more significant since Covid.

Interestingly, looking at the Educational Neuroscience site it has done work on the summer-born effect boys/girls, it might be one of those differences you mentioned that you haven’t considered. It says August-born girls are 5.5% less likely to achieve five A*-C grade GCSEs than September born girls, and the difference for boys is 6.1%[xiii]. A UK study of 11-16 year olds found that 66% of pupils receiving additional support were from the youngest quarter of the year (June to August born pupils).

http://www.educationalneuroscience.org.uk/resources/neuromyth-or-neurofact/children-do-better-in-school-if-they-were-born-in-the-autumn/#:~:text=August%2Dborn%20girls%20are%205.5,born%20pupils)%5Bxiv%5D.

Thanks for this Robert, I’m intrigued about the gender difference in the summer-born effect. And about how things have changed since the pandemic.

When I looked at this data a decade or more ago there seemed to me to be a positive effect of attending single sex schools for girls with below-average KS2. Did you look at that?

Hi Ralph. We didn’t look at this specifically: we controlled for prior attainment, but we didn’t break the outcomes down into subgroups. So there could be something in this. Given the high average levels of KS2 attainment for pupils in single sex schools, and the fact that such a lot of them are selective, I’d imagine that there are relatively few girls with below-average KS2 attended single sex schools, which would complicate things a bit.

Hi Natasha, thanks so much for this. A reaslly fascinating post!

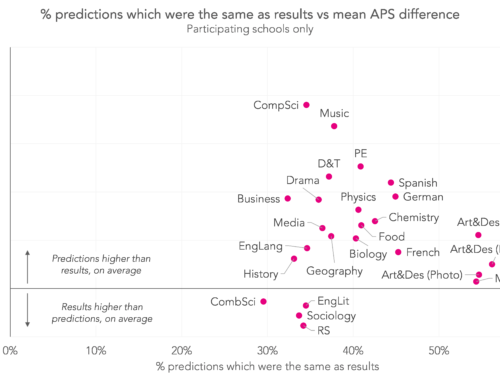

I’m guessing you didnt look at individual subjects in your analysis, but I imagine we’d see greater numbers of girls taking, attaining and progressing in otherwise heavily male-dominated subjects like physics, maths, computer science, design and technology etc. from single sex schools?

Rhys, Royal Academy of Engineering

Thanks Rhys! I didn’t look at individual subjects here, but it is something I’m very interested in and have written about in the past – once specifically about girls progressing to A-Level physics and once about attainment in ‘gendered’ subjects. And I’m sure there’ll be more to come!

Hi Natasha, Can ask who commissioned this piece of research?

Hi Emma. It wasn’t commissioned by anyone. We just thought it would be an interesting thing to look at.