Attainment 8 and Progress 8, the new Key Stage Four school accountability measures due to be introduced by Government in 2016, will undoubtedly make a difference to how schools enter their pupils for qualifications. They are reminiscent of the old ‘best eight or capped’ and ‘contextual value added’ measures in that they judge a school across a large number of subjects taught. But they are more restrictive because only some subjects count for inclusion: the first two slots must be filled by English and maths, the next three by EBacc subjects of science, computer science, history, geography, or languages, and the final three by any other GCSEs or eligible qualifications.

These new performance tables will, overnight, alter which schools are deemed to be doing well or poorly. And inevitably schools will adjust their curriculum offer to raise Attainment 8 (A8) performance. We predict that the new performance measures will change the narrative about which regions and local authorities are improving. Here, we focus on how adjusting subject entry patterns to ‘fill the slots’ can (and will) yield large improvements in Attainment 8 without any associated improvement in teaching quality. It is better for a pupil to enter at least five EBacc subjects, even if they are likely to do relatively poorly, because every grade from G upwards counts in the new measures.

Schools have already started filling the Attainment 8 slots

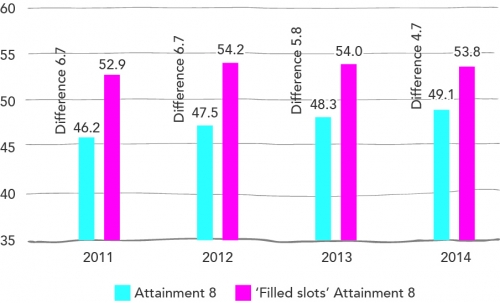

Although the Attainment 8 measure has only recently been announced, back in 2010 schools started altering the Key Stage Four curriculum to allow more of their pupils to have the chance of inclusion in the EBacc performance measure. This has resulted in Attainment 8 improving nationally from 46.2 in 2010 to 49.1 in 2014, even though it wasn’t yet devised as a performance monitoring tool.

If schools ensured that every pupil was entered for eight eligible qualifications and that the pupil managed to achieve the same average grade in them as they do for their current Attainment 8 subjects, then Attainment 8 would clearly rise further. We call this measure of the potential Attainment 8 achievable, holding constant average grades, the ‘filled slots’ Attainment 8 measure. In 2014, the Attainment 8 score would have risen by 4.7 to 53.8 if all Attainment 8 slots were filled by all children in all schools.

National actual and ‘filled slots’ Attainment 8 scores

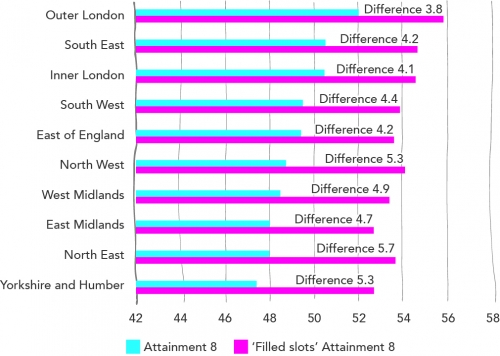

Northern regions have more opportunity to improve Attainment 8

Current regional differences in performance on Attainment 8 follow well-known patterns. Overall, achievement is higher in London and the south of England than it is in the north and the Midlands. However, those regions that are currently performing poorly also have the greatest opportunity to make rapid improvements in performance, simply by ‘filling the slots’ through curriculum change.

Differences between Attainment 8 and ‘filled slots’ Attainment 8 by region

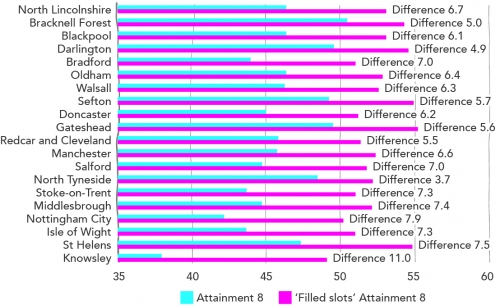

We think these local authorities should achieve the best improvements in Attainment 8

Those local authorities where schools offer a curriculum that is poorly aligned with Attainment 8 have huge opportunities to improve their performance, should they want to. There are no London and few southern local authorities on the list. Some areas will argue that a more traditional curriculum is not appropriate for children in their area or that they are not well equipped to deliver this new curriculum. It is interesting to note that most local authorities were offering a curriculum better aligned with Attainment 8 in 2004 than they were in 2014. At the extreme, in the past decade there has been over a 20 percentage point fall in the number of pupils entered for a full set of Attainment 8-aligned subjects in Bracknell Forest, Oldham, Doncaster and East Riding of Yorkshire. By contrast, Islington has seen a huge 23 percentage point increase over the same period.

Actual and ‘filled slots’ Attainment 8 points for 20 local authorities with the most potential to improve

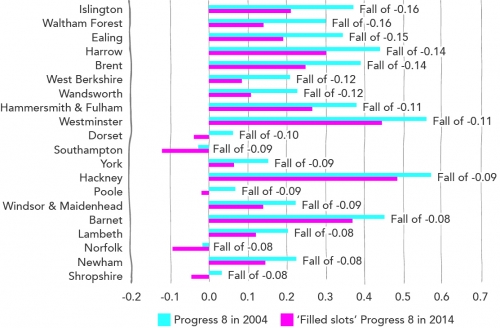

Beware of London’s deteriorating Progress 8 measure

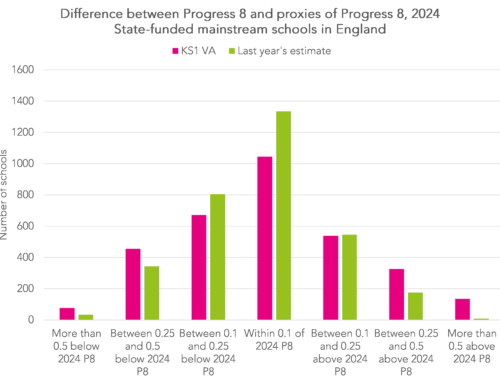

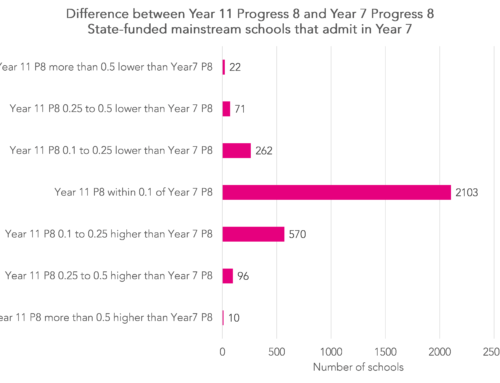

Progress 8 is calculated for each child by comparing their Attainment 8 score to that of all other pupils scoring the same Key Stage Two fine grade. This is then averaged across all pupils to give the school’s Progress 8 measure. As an accountability measure, a value below -0.5 (i.e. pupils scoring on average half a grade below expectations or entering fewer than average number of subjects) will be the new floor standard, triggering scrutiny through inspection.

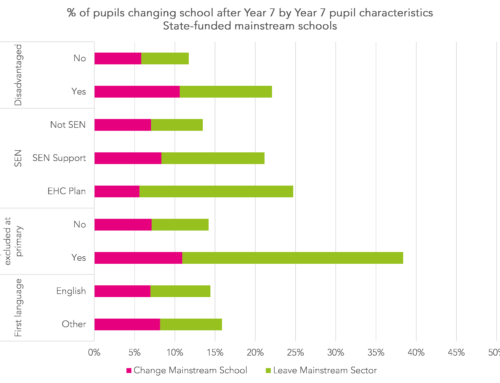

In 2014, almost 300 schools would have fallen below the floor standard (even taking the best entry of the pupil, rather than their first entry in the subject). As more students enter for more eligible qualifications, the distribution of Progress 8 will shrink – at least 100 of these schools below floor standard can remove themselves from scrutiny through curriculum reorientation alone.

London performs well on Attainment 8 and will continue to perform well even as schools in other regions start to realign their curriculum to the new performance measures. However, as some schools enter more students for qualifying subjects, the comparison for those schools and areas already doing well becomes increasingly difficult. The areas where there is little room for improvement through ‘filling the slots’ are mostly in London and so it is reasonable to assume that many schools here will see deteriorating year-on-year Progress 8 scores.

These local authorities will need to explain why Progress 8 is deteriorating, even if Attainment 8 is improving

These new accountability measures will force schools to think again about how they enter pupils for qualifications, and will encourage them to ensure progress is made by pupils at all levels, rather than just at the C/D grade threshold. The measure should allow the rest of England to start to catch up with London by better aligning their curriculum to fill the Attainment 8 slots.

By contrast, schools already offering a traditional curriculum can only improve by raising individual subject grades. This presents a rather unanticipated risk: schools with a traditional curriculum – those with higher entry attainment of pupils, grammar schools, schools in London – focus their energy on improving teaching and grades since this is the only way to raise Attainment 8. Meanwhile, the reorientation of the curriculum distracts others from maximising individual subject grades. Thus, Attainment 8 thus converges, yet average subject grades diverge.

‘Progress and Attainment 8’ presents a new challenge in the heads’ Herculean game of trying to square what’s good and fair for the individual with what’s good for the school. They want both, but they can’t always have it.

This will tip the odds slightly in favour of getting it right for the pupils, particularly those who at present gain least from the system: the biggest points gain for the school is going to lie in raising the results of those pupils who arrive with less rather than more prior attainment. And not publishing five or more will change the media-driven public’s perception of how a school should be judged on exams, which in an ideal world should be taken when pupils are ready, rather than at a pre-determined age.

Tim Brighouse, Norham Fellow at University Department of Education Oxford

Measurement is rarely neutral. People and organisations respond to being measured. Sometimes, if policy makers have done a good job, they respond in the way intended. But people are smart and will respond to the fine detail of whatever is measured, rather than to the spirit.

This analysis explores the implications of some possible reactions of schools to the new accountability framework. It assumes that schools will make use of an easy hit to raise their Attainment 8 and Progress 8 scores by filling any currently-empty Attainment 8 slots – they’re almost certainly right.

To understand the full effect of such a move by schools, we need to know what schools and pupils would be giving up to move to what the piece calls a more traditional curriculum. Was what the pupils were doing before truly valueless? Could teachers of vocational qualifications that have been ‘Wolfed’ simply turn to teaching history instead? While the broad prediction of a relative improvement in parts of the north of England seems right, there will be enough twists and turns to keep all us analysts very busy.

Simon Burgess, Professor of Economics, University of Bristol

Leave A Comment