Earlier today at the Festival of Education I hosted a panel session with Jack Marwood and Michael Tidd that asked whether high stakes primary school tests can ever serve the interests of children.

Michael Tidd has, through his blogs, tweets and newspaper column, publicly held the Government to account through the repeated missed deadlines on SATS guidance this year. He is now monitoring how schools are deciding to implement the assessments in practice. Jack Marwood is one of the most statistically eloquent critics of how school tests are used, constantly reminding us that teachers in the classroom are just the ‘icing on the cake’, sitting atop a multitude of factors that determine how well a child performs in a test.

I wanted to host this panel because recent changes in primary school accountability are having a daily impact on the experiences of children in the classroom, yet they seem to be under less scrutiny than the secondary school accountability that I have spent most of my career studying. In our session we covered some of the issues around (1) what we choose to test in primary schools; (2) when and how we choose to test it; and (3) how we then choose to use the assessment data we create.

There is a serious curriculum-testing mis-match at Key Stage 2

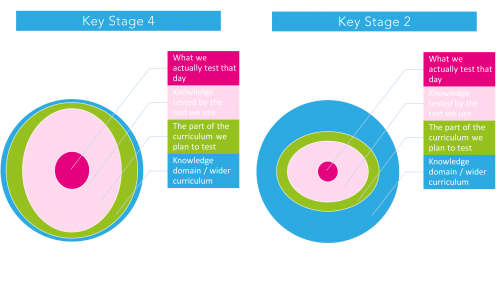

One major difference between Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 4 is the relationship between the curriculum we set and the tests students sit. Whereas at KS4 we essentially test everything we teach, except games and personal/social education (and do so fairly robustly by taking weeks to sit the tests), at KS2 we only test maths, reading, writing and grammar.

This leads to the rather strange juxtaposition where some of the greatest critics of the KS2 tests find themselves arguing that we need more tests to avoid the curriculum restriction that takes place, especially in year 6! Neither Jack nor Michael were particularly in favour of explicitly testing new subjects such as history or broader synoptic tests. Instead, Michael advocated narrowing the curriculum for the right year groups in the right way, by focusing solely on reading, writing and maths up to year 4, thus freeing years 5 and 6 to introduce a broader curriculum once the basics were mastered. Jack, though generally a high stakes testing sceptic, doesn’t mind limited tests to drive school behaviour, such as the phonics tests, and also thinks a times table test in year 4 could be useful.

Jack would prefer we remove universal testing at Key Stage 2 altogether and replace it with sample testing, rather like the National Reference Test, to check national standards are maintained. Michael pointed out that this has already happened for KS2 science with the consequence that it is no longer a focus for teaching.

I suggested that, rather than try to write a test worth teaching to, we could create tests that it was impossible to prepare for because they are not revealed in advance. This is how PISA works. Teachers will still, of course, teach towards the knowledge domains which they expect to be tested, but it reduces the weeks or months of practice questions, teaching children the mark scheme, test sitting strategies, etc…

Teacher judgment or external assessment both ‘label’ children, but in different ways

There is a genuine concern from many parents and teachers about how high stakes tests attach labels to children’s attainment that may, in turn, affect self-concept and how those children are managed through the rest of their educational career. For one audience member, she wanted her child to start year 7 without this label that told the secondary school what sort of GCSE results her child was likely to achieve. Another was particularly concerned about how SEND children fared in tests.

However, Michael pointed out that judgments will be made on student capabilities and attainment, and we shouldn’t assume that a teacher’s judgment in the absence of test data will be more accurate or indeed fairer. The cognitive shortcuts that teachers make to judge pupils, and their impact on certain ethnic minorities, have been written about elsewhere. And for some SEND children, they might demonstrate capabilities in a particular test that have been overlooked in the classroom.

The case for ‘lowering the stakes’

At the debate we didn’t have time to talk about the reliability and validity of the judgments we make on schools. Primary school ‘performance’ from one year to the next hangs on the test papers of relatively few pupils. I suspect that if we properly measured the reliability and validity of the value-added judgments we make on primary schools, it would reveal how fragile they are (research project, anyone?).

Both Jack and Michael feel that we can hold schools to account for the quality of the education they provide without publishing league tables, and that this would mitigate many of the negative effects of tests. Jack wouldn’t want Ofsted to have access to this test data either, because he feels it renders the inspection meaningless where they make a judgment that simply mirrors the data itself. Michael feels that the short two-day inspection would be impossible without performance data and that Ofsted, alongside other stakeholders such as governing bodies, LAs and MATs, should use it to hold schools to account.

We should aim to lower the stress for children in 2017

The SATs tests this year were possibly the most stressful so far from the perspective of the year 6 pupils. Michael argues that the uncertainty created by Government around the arrangements themselves raised stress levels for teachers that in turn fed into pupil stress. Jack feels that it is very hard to make high stakes tests anything other than stressful for children. But both agreed that, whilst we should not blame teachers for raising the stress levels of children, they do now have an ethical duty to everything they can to minimise the significance of the testing week for the children.

Re-balancing the hopes and fears for high stakes testing

Accountability, at its best, ensures that:

- Teachers are incentivised to work more effectively (or harder)

- Resources are directed towards the curriculum that society has chosen for its children

- Poor quality teaching and bad ideas are driven out

- Outstanding practice can be identified, celebrated and replicated

But when we get the balance wrong it can lead to excessive teacher stress and resignations, narrowing of the curriculum, excessive coaching to the test, threats to professional autonomy, manipulation of pupil intakes, cheating, and stress for children.

I think we can do a better job of reducing some of these downsides whilst preserving the benefits of the testing regime. I suspect Jack’s ideas are too radical to get taken on by government, but we need more teachers like Michael and Jack who commit to being experts in assessment so that the teaching profession can advocate for improvements to the tests and their uses.

I hope that more primary school teachers will commit to learning more about assessment. A brilliant place to start is by reading Koretz’s book ‘Measuring Up’.

Leave A Comment