This is the second of two blogposts about an article we’ve recently had published in the British Educational Research Journal on the impact of the reforms to school accountability introduced following the Wolf review of 2011.

In part one of this series we looked at the impact of reforms brought in following the Wolf review on Key Stage 4 attainment and entries for a group of pupils we considered to be most likely affected. (For a summary of what those reforms were, read part one.)

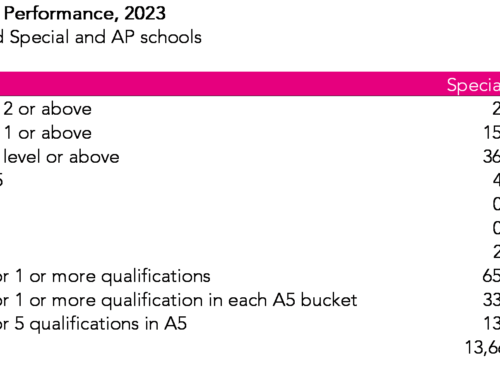

We found that they took more GCSEs but fewer qualifications overall. Proportionately fewer achieved the equivalent of five or more A*-C grades at GCSE, traditionally considered to be the minimum level of attainment for progression to Level 3 study post-16.

In this part we look at what happened to these young people post-16, and offer some overall conclusions from our work.

Post-16

We constructed post-16 study profiles for our group of interest, using qualification learning aims collected through the school census for those who were in school in the year following Key Stage 4 and the individualised learner record for those who were in colleges.

This was done for three cohorts: those who completed Key Stage 4 between 2012 and 2014. The 2014 cohort was the first to be affected by the Wolf reforms but the 2013 cohort was the first to be affected by another policy, the raising of the participation age.[1]

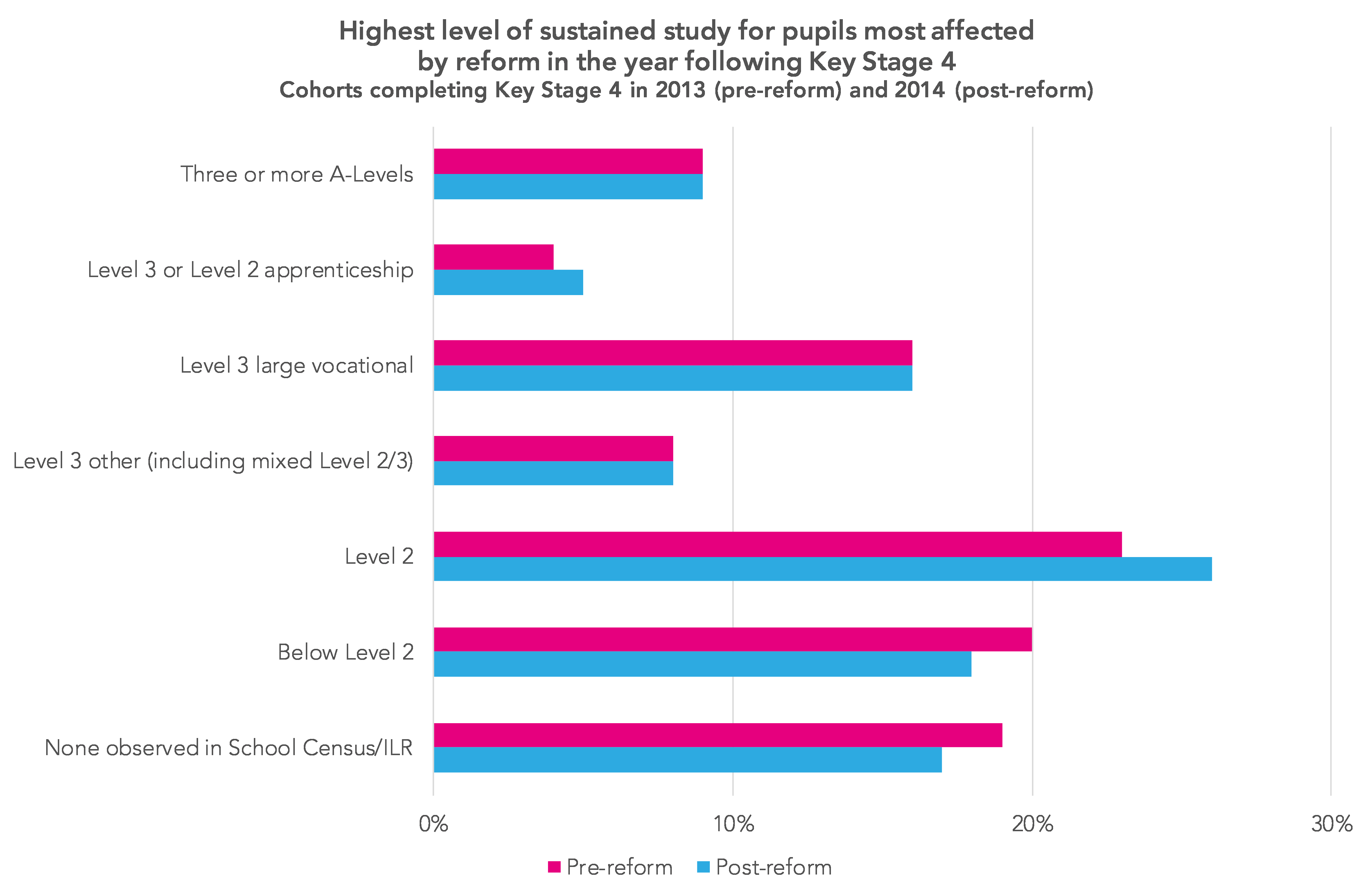

The chart below looks at sustained learning – courses that pupils pursued for at least 180 consecutive days.

If anything, the post-16 sustained study choices of the post-reform cohort were slightly improved. Similar proportions opted for Level 3 study. Fewer studied qualifications below Level 2, and fewer were not observed to be in sustained learning. This does not mean that they did not engage in any learning, just that they did not pursue any learning aims for 180 consecutive days.

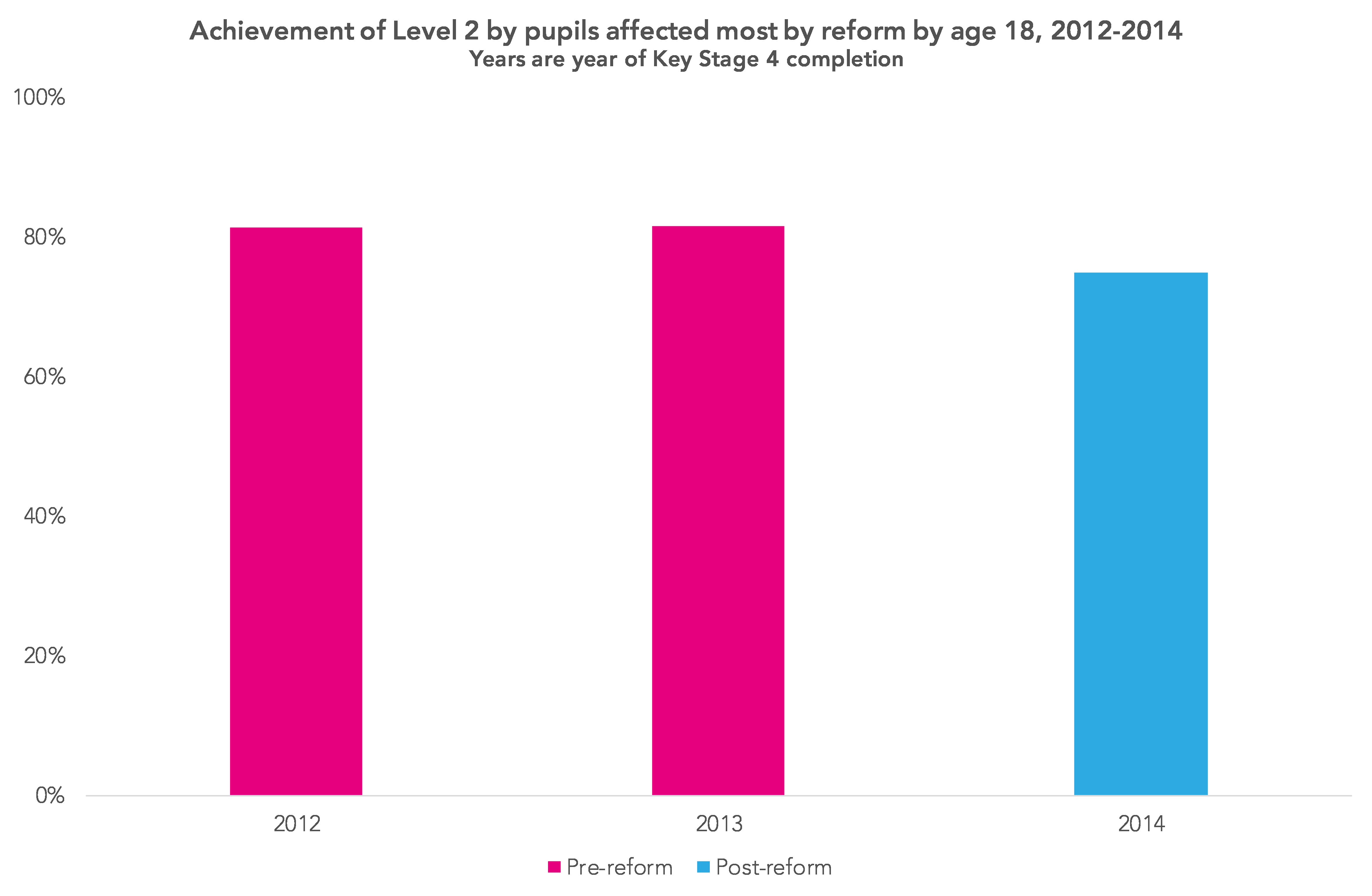

However, when we come to look at attainment by age 18, the post-reform cohort were less likely to have achieved five or more A*-C grades at GCSE or equivalent (Level 2 of the National Qualifications Framework) than their counterparts in the pre-reform cohorts, as the chart below shows.

The 11 percentage point difference in Level 2 attainment observed at the end of Key Stage 4 in part one of this series narrowed slightly by age 18 but remained at almost seven percentage points.

Conclusion

So, what can we say was the overall impact of the Wolf review? It led to wholesale changes in the set of qualifications that schools offered to pupils, particularly lower-attaining pupils. The policy was implemented by assigning zero value to the ineligible qualifications in school performance tables, thereby removing any performance incentive for schools to enter pupils in them.

The qualifications primarily affected were those for students typically following a less academic curriculum. Many schools changed the portfolio of qualifications they offered, reducing the number of those deemed ineligible.

In terms of attainment, the group who previously were most likely to enter these qualifications now took more GCSEs, but scored about the same or slightly worse on them compared to similar pupils in previous cohorts. They took fewer non-GCSE qualifications.

The overall change in attainment for this group was a fall in the percentage of pupils achieving five or more A*-C grades at GCSE (or equivalent at age 16) from 72% in 2012 and 2013 to 61% in 2014.

Of course, it is difficult to judge the meaning of this outcome. If the previous qualifications were of little value, then perhaps nothing much changed.

By age 18, the percentage of pupils in the group of interest achieving five or more A*-C grades at GCSE or equivalent had increased to 75%, but this was still 6-7 percentage points lower than their counterparts in previous cohorts. This was despite taking very similar post-16 study options at 17.

The Wolf reforms significantly changed the landscape of qualifications in England, and certainly had an effect on the portfolios of qualifications offered by schools. While we await early labour market data for the cohorts before and after these reforms, there is no evidence from the attainment data that these reforms helped lower-attaining pupils.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. Initially the participation age was raised to 17. It was then raised to 18 for the subsequent cohort (the 2014 KS4 cohort).

Leave A Comment