This is the first of two blogposts about an article we’ve recently had published in the British Educational Research Journal on the impact of the reforms to school accountability introduced following the Wolf review of 2011.

Say what you like about Michael Gove’s time as education secretary, his reforms have certainly given us plenty to write about over the last few years.

In an article recently published in the British Educational Research Journal, we look at the impact of the reforms introduced following the Wolf review of 2011.

These reforms significantly changed the landscape of qualifications in England, and certainly had effects on the portfolios of qualifications offered by schools. While we await early labour market data for the cohorts before and after these reforms, we are able to look at attainment at age 16 and 18.

In this blogpost, we’ll look at the impact of these reforms on Key Stage 4 attainment, while in part two we’ll look at post-16 study choices and attainment.

Spoiler: We don’t find that the reforms helped lower attaining pupils.

Accountability reforms following the Wolf review

Although ostensibly about vocational education, the review led to seismic changes for one of the main accountability levers, school performance tables.

These changes, implemented for the 2014 secondary school performance tables (published in January 2015) were as follows:

- A raft of qualifications approved for 16-year-olds, such as short course GCSEs, were deemed ineligible for performance tables measures;

- Qualifications could only be counted as equivalent to a single GCSE (previously some qualifications counted as up to four GCSEs);

- Only two non-GCSEs could be counted per pupil.

In addition, and unrelated to the Wolf review, the first result achieved by a pupil in a given GCSE would henceforth be counted rather than their best result. This was to counter the practice of repeatedly entering pupils for English and maths to try and ‘bank’ a C grade.

On the whole, the response of schools was to enter pupils for more GCSEs and fewer non-GCSEs. However, there was considerable variation in response between schools. For some schools, it made little difference. They were already delivering GCSEs and little else besides. For others it made much more difference.

Which pupils were most affected?

In our analysis, we were mostly concerned by the change to which qualifications would count towards performance table measures.

We tried to identify and then focus on the group we thought were most affected – namely those who would otherwise have taken a large number of qualifications that were no longer eligible for performance tables.

We did this by looking back to the 2012 Key Stage 4 cohort, who were unaffected by the reforms. We identified a group of pupils who:

- were entered for three or more qualifications that were to be deemed ineligible for performance tables from 2014 onwards; and

- entered fewer than eight qualifications (in GCSE equivalents) that were to be deemed eligible for performance tables from 2014 onwards.

Just over 71,000 pupils (13% of the cohort) were identified as belonging to the group.

We then attempted to identify pupils most at risk of being affected by the Wolf reforms from 2014 onwards.

We estimated the probability of membership of this group as a function of prior attainment, free school meals eligibility, special educational needs, gender, ethnicity and school attended, the key factors being low prior attainment and disadvantage.

Impact on entries and attainment

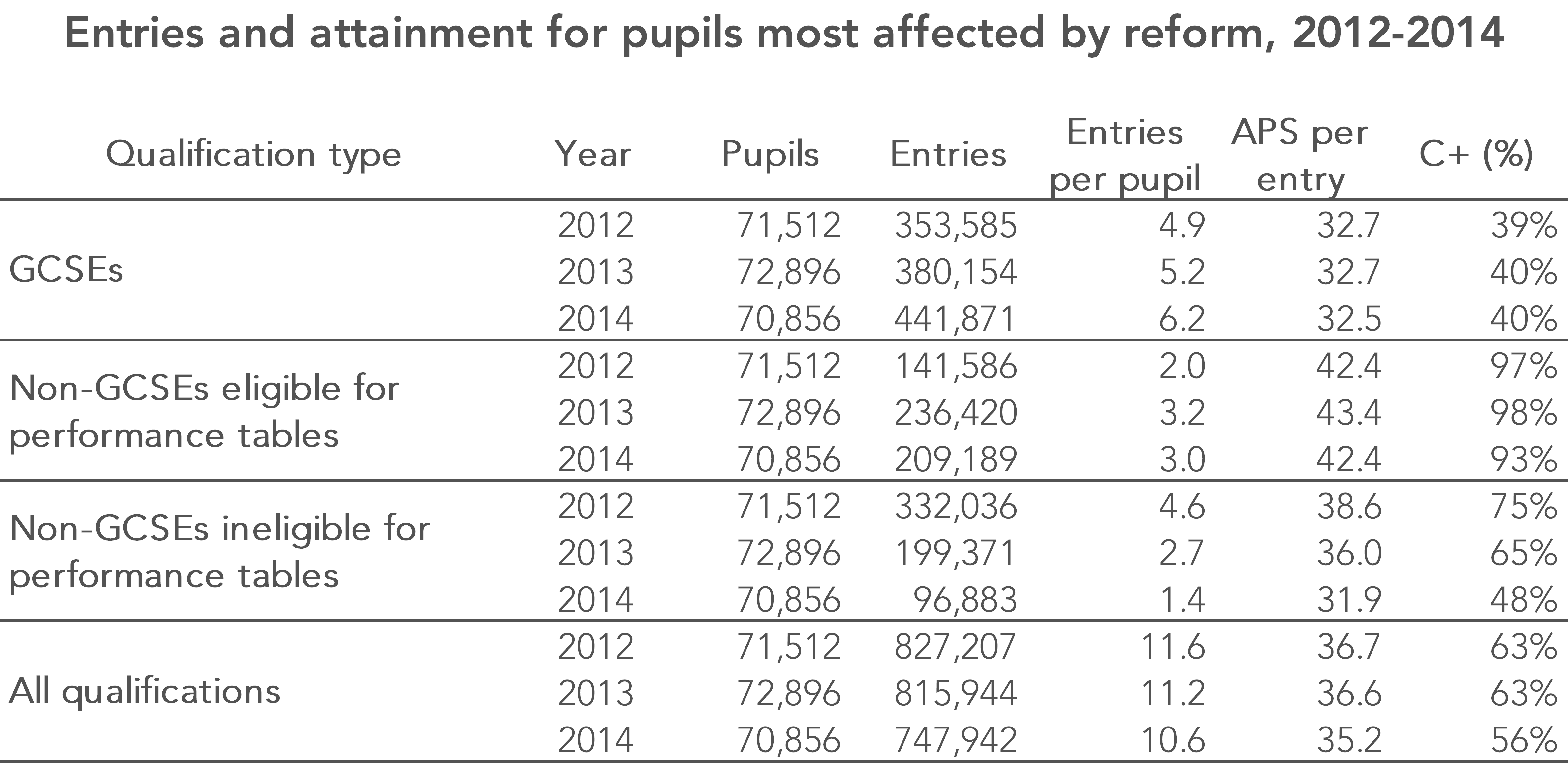

In our paper we used the prevailing method of converting grades to points, where grade G in a GCSE yielded 16 points and an A* 58 points. To ensure comparability between years, we also went through the process of recalculating all the 2014 attainment measures so they were consistent with previous years.

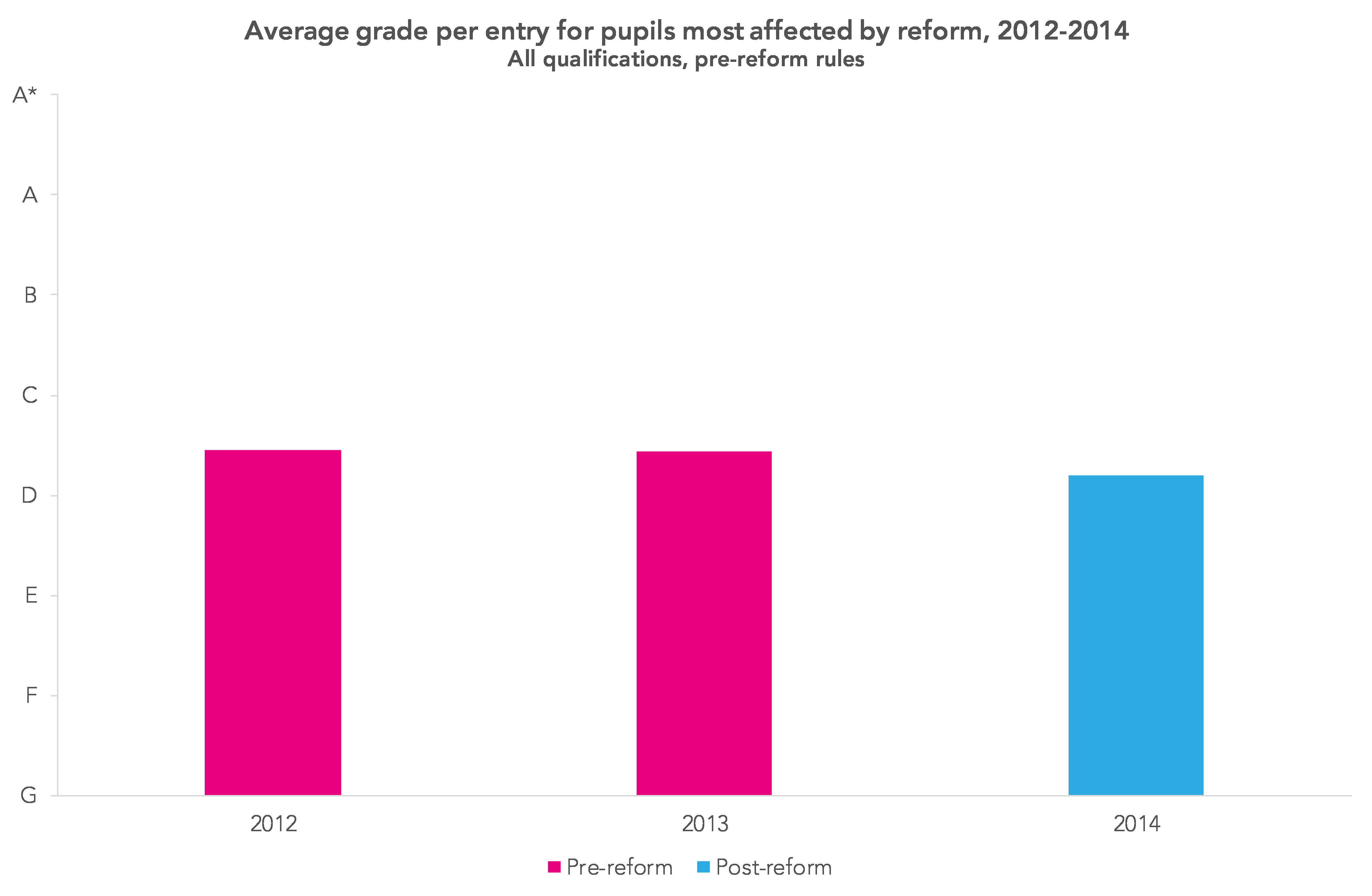

The bottom line is that the average point score per entry (APSE) for our group of interest fell from 36.7 (roughly midway between grades D and C) to 35.2, the equivalent of a quarter of a grade per subject. In Progress 8 terms this is equivalent to a fall of 0.25.

However, this was the result of pupils entering different qualifications rather than achieving worse grades.

The APSE in GCSEs fell only fractionally – from 32.7 to 32.5 – between 2012 and 2014. Entries in GCSEs increased markedly from 4.9 to 6.2, but entries in all qualifications fell from 11.6 to 10.6.

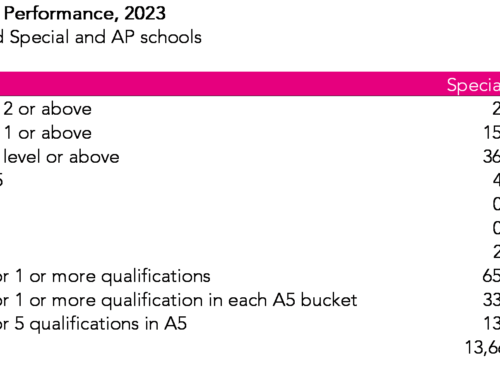

Both attainment and number of entries fell in ineligible qualifications, however. The APSE in 2012 was 38.6 (a full grade higher than the APSE in GCSEs), falling to 31.9 in 2014. Entries fell from 4.6 per pupil to 1.4. More detail is shown in the table below.

Impact on overall attainment

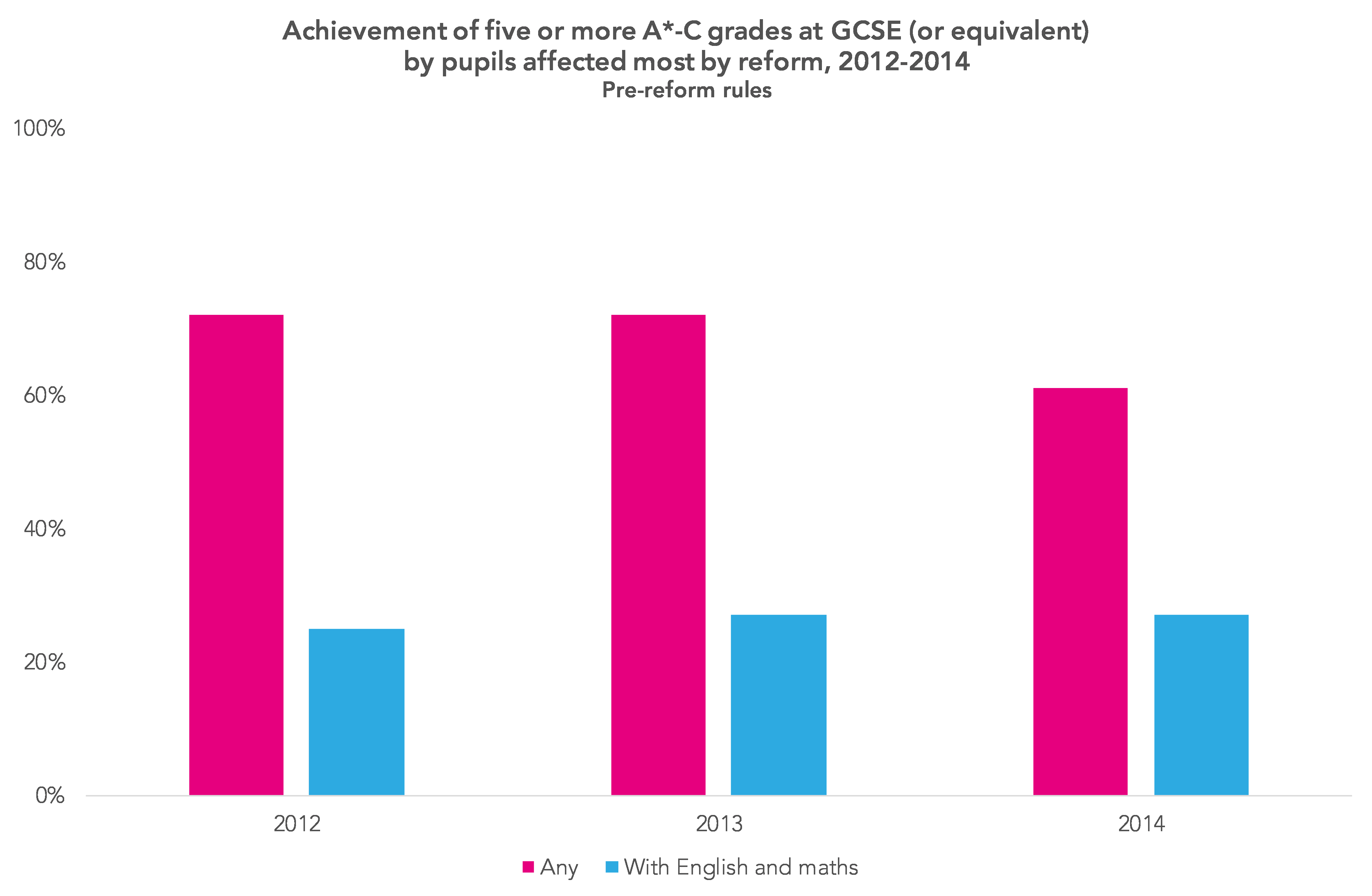

There was hardly any change in the percentage of pupils in our group of interest achieving five or more A*-C grades at GCSE including English and maths.

Leaving aside English and maths, though, the percentage achieving any five or more A*-C grades (or equivalent) fell by 11 percentage points from 72% to 61%.

This can be attributed to schools tending to enter pupils for fewer large non-GCSE qualifications and instead pursuing GCSEs.

Conclusion

In short, the reforms had an effect on the types of qualifications pupils entered, with a shift from more generously scored GCSE-equivalent qualifications back to GCSEs. Pupils took more GCSEs but fewer qualifications overall. However, attainment in different types of qualification did not change much.

Perhaps this is only to have been expected, given the method of comparable outcomes [PDF] employed by Ofqual and awarding bodies to ensure consistency in grading from year to year.

In the next part, we will look at what happened to the group of interest post-16 and offer some overall conclusions.

Now read part two of this series: Crying Wolf? Part two

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment