This is the first part of a two part blogpost. The second part can be found here.

Back in February, Gavin Williamson made some unkind remarks about “dead-end courses that give [students] nothing but a mountain of debt”. He’s since announced cuts to funding for university arts courses.

Time will tell whether the new incumbent will continue down the same path. In the meantime, there’s been growing concern in some quarters that the government’s partiality to STEM degrees over arts courses will lead to the devaluing of subjects such as English, art, music and drama and further declines in the numbers choosing to take arts degrees.

But for these subjects, the rot sets in well before degree level; A-Level numbers have been on a downward trend for some time.

In these posts, we’ll dig into the figures to examine that downward trend in more detail, look at the demographics of the students choosing to study arts subjects at A-Level and whether they are changing as numbers decline.

This first post will focus on English.

English vs maths

When analyzing GCSE results, it’s very common to look at English and maths together. As the two compulsory subjects, they’re taken by far more pupils than any other subject and are a useful benchmark.

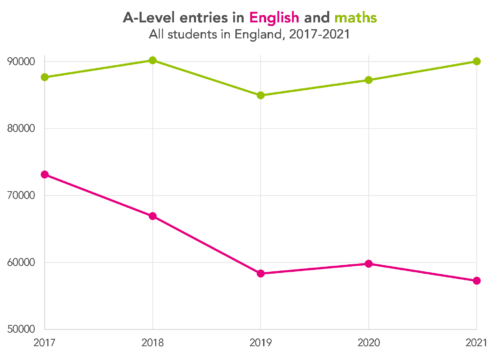

At A-Level, maths is still taken by more students than any other subject, but English doesn’t fare quite so well. As recently as 2018, it was the second most popular subject but it currently languishes in fourth place behind maths, psychology and biology.

We should note that so far we’ve lumped all entries to English A-Levels together, although there are actually three options available – of which more later.

As entries in English have fallen, those in maths have remained broadly stable, and the gap between the two has been steadily increasing from just under 13,000 students in 2017 to nearly 33,000 in 2021.

Literature, language or both

Although we often talk about English A-Level as if it was a single subject, there are actually three options available: English language, English literature, and English language and literature.

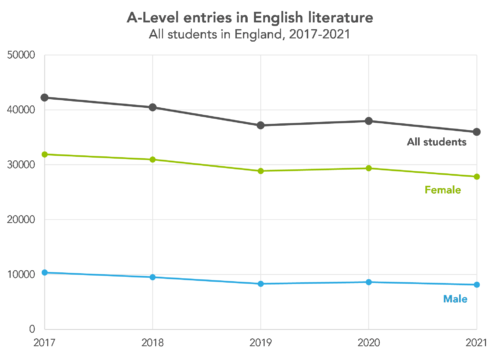

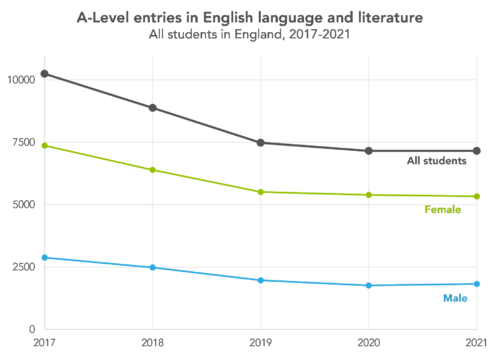

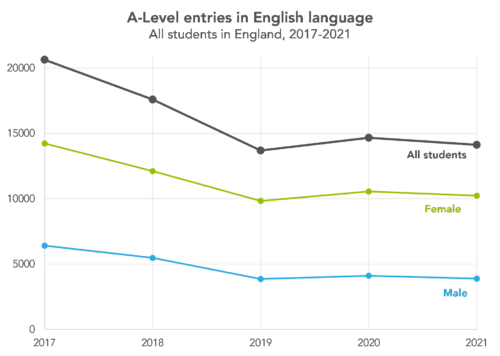

The majority of students who choose to study English at A-Level select English literature, while the combined A-Level in literature and language is somewhat niche; 63% of A-Level students who took exams in English this year studied literature, 25% language and just 13% the combined A-Level.

To set the scene, we’ll use some of the analysis available on our results day microsite. The graphs below are available on the site, and you can also explore trends in other subjects. [1]

Results analysis microsite

Our results microsite provides analysis of national GCSE and A-Level results in England, Wales and Northern Ireland from 2016 to 2021. Using publically available data from JCQ, it includes information on entry numbers and grades, broken down by subject and gender.

All three English A-Levels have seen a fall in entries over recent years but these have been less steep in English literature than in the other two options. English literature and particularly English language had a bit of a recovery in 2020, reversing the trend of the previous three years. But numbers fell again in 2021 and remain far below what they were in 2017.

It’s also clear from the graphs that English is a subject that’s much more popular with female than male students.

Demographics of English students

From this point onwards, we’ll be using data from the National Pupil Database (NPD) rather than publically available data from JCQ so that we can go into more detail about which students choose to study English.

The graph below shows the characteristics of English A-Level students in 2020, the most recent year for which data is available from the NPD.

As we’ve already seen, the majority of A-Level English students are female, particularly in English literature, which had the second highest proportion of female students of all A-Level subjects in 2020.

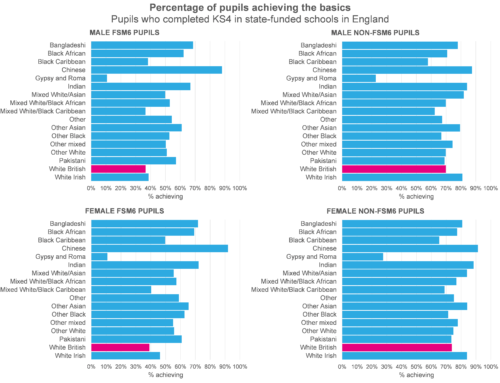

English language is less popular with students from ethnic minorities; 83% of students for whom we have data on ethnic background were white in 2020 compared to 73% of all A-Level students. This was less true of English literature, in which 73% of students were white, very close to the overall figure.

English literature is also very close to the average proportion of disadvantaged pupils; 14% were disadvantaged in 2020 compared to 13% overall, while the combined A-Level had a higher proportion of disadvantaged pupils at 16%.

Finally, we divided pupils into terciles based on their average points score in GCSEs or equivalent.[1] We found some striking differences between the three options here. English literature students are more likely to have high (36%) or medium (36%) prior attainment, although a sizeable chunk (28%) do come from the lowest third. But just 17% of English language students and 17% of students taking the combined A-Level had high prior attainment.

Which students have stopped choosing English?

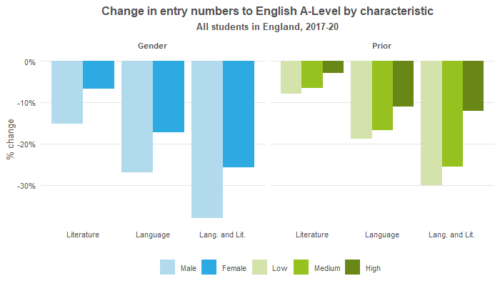

We’ll now take a look at how the characteristics of English A-Level students have changed since 2017. This should tell us whether any group of students is particularly likely to have turned away from studying English in recent years.

In all three English options, the number of students with high prior attainment has decreased by a relatively small amount since 2017, but the number of students with medium and low prior attainment has fallen more.

Similarly, although the numbers of both male and female students taking English has fallen, the number of male students has fallen more sharply.

We should also note that there have been some differences in the number of students who are disadvantaged and who are white taking English, but these reflect changes in the overall A-Level population.

It looks as though male students with medium and particularly low prior attainment have been more likely to move away from English A-Level than others.

Some speculation about STEM

So are students choosing to study STEM instead of English?

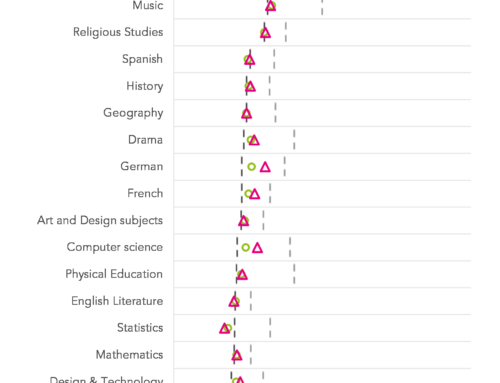

The number of A-Level entries in STEM subjects such as physics, chemistry and especially computing have been increasing over the last few years (although biology and maths have remained fairly static). But there are some other possible culprits in which numbers have also increased, namely the social sciences, particularly psychology and sociology.

As we’ve shown in a previous post on A-Level subject combinations, students who study physics and chemistry often select an all-STEM group of A-Levels, while students who English tend to match it with humanities or social sciences.

So if students are moving from English to physics or chemistry, we might expect them to be moving away from the subjects commonly matched with English as well and turning instead to a STEM-dominated choice.

Numbers in history – the subject most commonly matched with English – have been somewhat volatile, but on the whole have been declining, but numbers in psychology and sociology – the second and third most common matches – have increased quite sharply over the last few years.

Summing up

After all that, we haven’t really come to any firm conclusions about what students are choosing to study in place of English.

It’s possible that some of them are having a radical rethink and opting for physics and chemistry instead. Others may be turning instead to the social sciences. It’s likely that the true answer is a combination of both of these and other options.

So while there is some evidence to support the idea that some of the students who would once have studied English are looking at STEM options in its place, it’s certainly not overwhelming.

- We excluded any pupils who took their GCSEs prior to 2017 from this part of the analysis. The low attainment tercile includes pupils with an average points score between 0 and 5.3, medium between 5.3 and 6.5, and high 6.5 or above.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Might one argue that those no longer choosing English in any form are instead choosing Psychology and Sociology? If so, might that be that they are perceived at school as being marginally more ‘useful’? Or is it perhaps that there are enough teachers of these subjects available so that they can be offered? Might that point to a historic trend based upon graduates in theses subjects? Put that another way, is there any correlation between the number of subject graduates and the number of teachers of the matching subjects? In STEM terms this might point to research into, say, the numbers of non-maths graduates teaching maths (e.g. engineering graduates).