Much has been written over the last couple of years about how the COVID-19 pandemic – through a combination of lockdowns, home schooling and self-isolation – has affected the mental wellbeing of young people.

Yet, even before COVID hit our shores, there was growing concern over young people’s mental health. Amongst educationalists, there was particular interest in how this might be linked to their experiences at school.

In this blog, drawing upon data from the pre-COVID era, I take a closer look into the link between schooling and mental health. Specifically, I consider how the treatment of mental health issues varies during children’s time at secondary school, teasing apart the impact of being in a more senior school year group from the effects of age.

Some basic facts

The data I use are drawn from appointments made with primary and secondary healthcare providers in England (e.g. GPs, hospitals), and the outcomes resulting from them. With this information, it is possible to track the contacts young people have made with healthcare providers since they started school.

(For further details, the academic paper this blog is based upon is available here.)

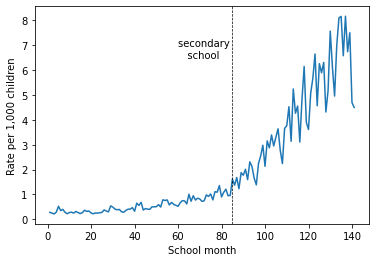

Firstly, as the chart below shows, contact with healthcare providers regarding issues related to mental health are very rare during primary school, but increase sharply during secondary school.

Mental health problems amongst children by their time at school

Number of contacts per month

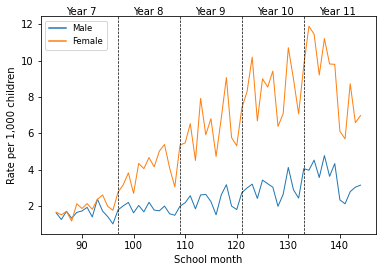

Importantly, this increase in the trajectory during secondary school differs significantly by gender.

Mental health problems of children by time at secondary school

Differences by gender

Note: “School month” refers to the number of months since children entered school.

The chart above shows that while there is only a comparatively small uptick in the case rate for boys, there is a much more appreciable increase for girls (up from around two per 1,000 children in Year 7 up to around 10 per 1,000 children in Years 10/11).

But what is driving this increase? Is it related to young people moving into a more senior school year group, and the potential academic and social pressure that this comes with? Or is it simply due to being biologically older, and the associated challenges that adolescence brings?

Age – rather year group – is key

To try and tease these factors apart, I restrict my focus to children in different school year groups, but who are of similar age. For instance, I compare summer-born Year 11s to autumn-born Year 10s, summer-born Year 10s to autumn-born Year 9s, and so forth.

In doing so, I recognise that such comparisons may still overestimate the impact of school year group (net of the effects of age) for two reasons. First, previous research has shown how being young compared to one’s school peers may also be related to mental health problems. Such “relative age effects” are hence likely to confound my results. Second, even when comparing autumn and summer-born children, there remains some (albeit small) difference in absolute age (of around three months).

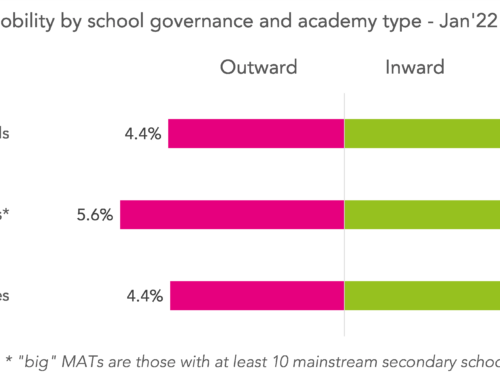

In other words, the results presented below are likely to provide an upper-bound of the true effect of school year group. The key findings from these comparisons are shown in the chart, below.

Source: Jerrim (2021: Table 1)

On the whole, most differences are quite small. For instance, the case rate per 1,000 children is similar across similarly aged pupils in Year 11 (5.9) and Year 10 (5.3). The same hold true for the difference between Year 10 (7.3) and Year 9 (6.8) and, indeed, for most of the other comparisons made. The only potential exception is for the comparison between Year 9 and Year 8, where some evidence of a sizable difference emerges.

The evidence presented here therefore suggests that the impact of school year group upon young people’s mental health is minimal. The striking increase in mental health diagnoses and treatments presented at the beginning of this post are primarily being driven by differences in biological age.

The link to the academic research this post is based on isn’t working. Please can you share it with me?

Thanks!

James

Hi James. Sorry for slow response. I’ve just tested the link and it seems fine (https://bera-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/berj.3769). There’s also an eprint at https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10137786/