We last looked at attendance at the end of the first Autumn half-term, and the tale was a familiar one: pupil absence was broadly in line with the previous year, but remained some way above pre-pandemic levels.

However, since then, we’ve had an unusually early flu season, with school-aged children seeing particularly high rates of infection. Today, we’ll look at the impact on absence, using attendance marks from around 10,000 schools subscribed to FFT Attendance Tracker. These cover the period up to and including Friday 19th December.

Overall absence by week

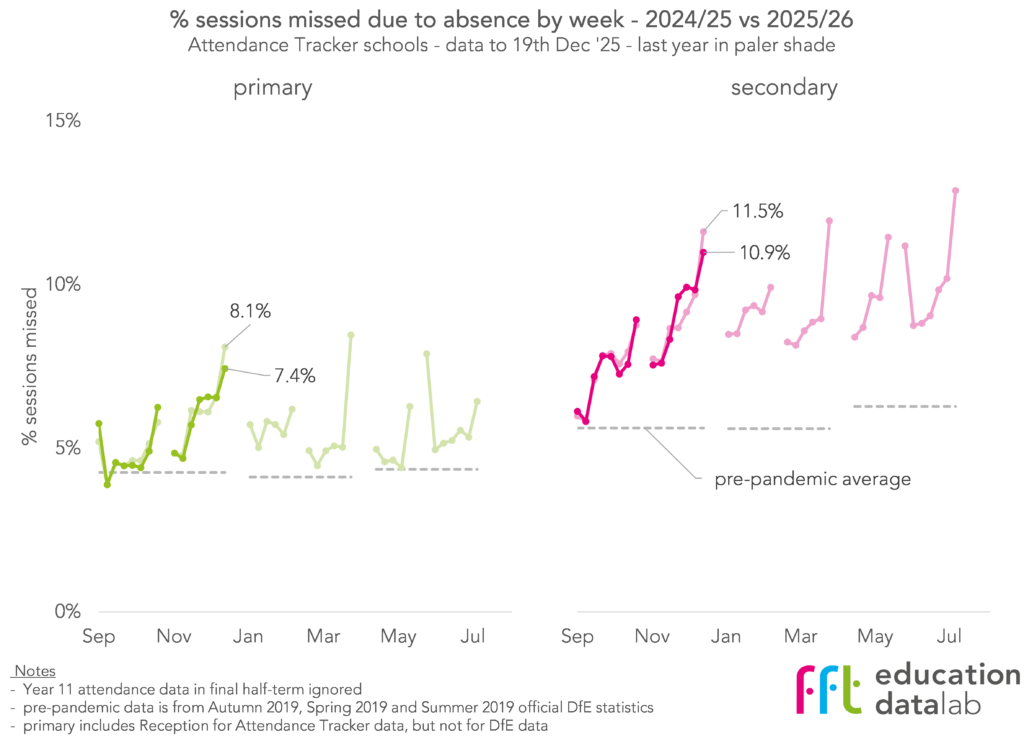

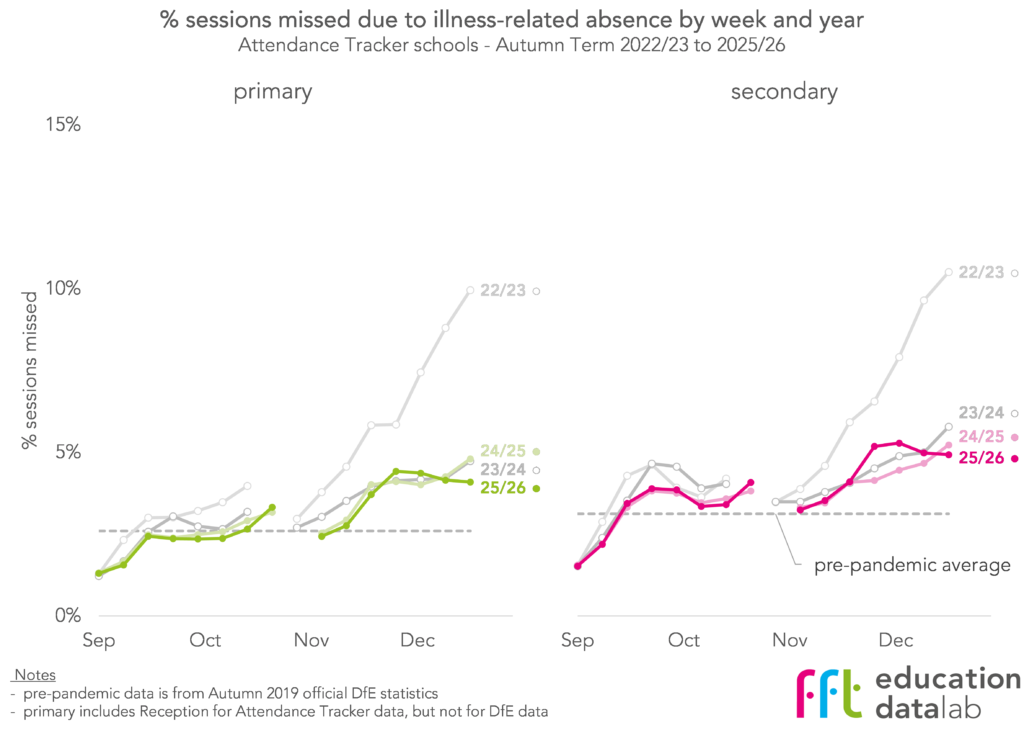

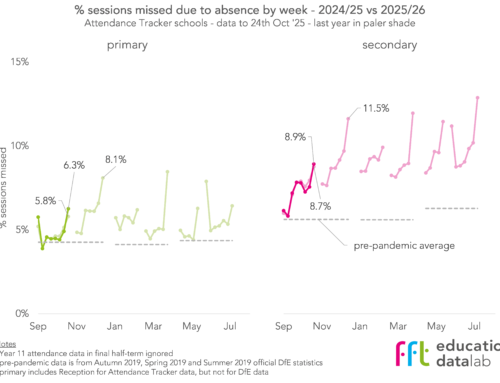

To start, let’s look at the percentage of sessions missed due to absence each week so far this year, and compare with the equivalent weeks last year. We’ll also add the pre-pandemic termly[1] averages.

In the first two weeks of the second half-term, absence rates were broadly in-line with the previous half-term, before increasing and peaking the week before the Christmas break. We see the same pattern in last year’s data too. It does seem, however, particularly at secondary, that the increase through November was more rapid this year than last.

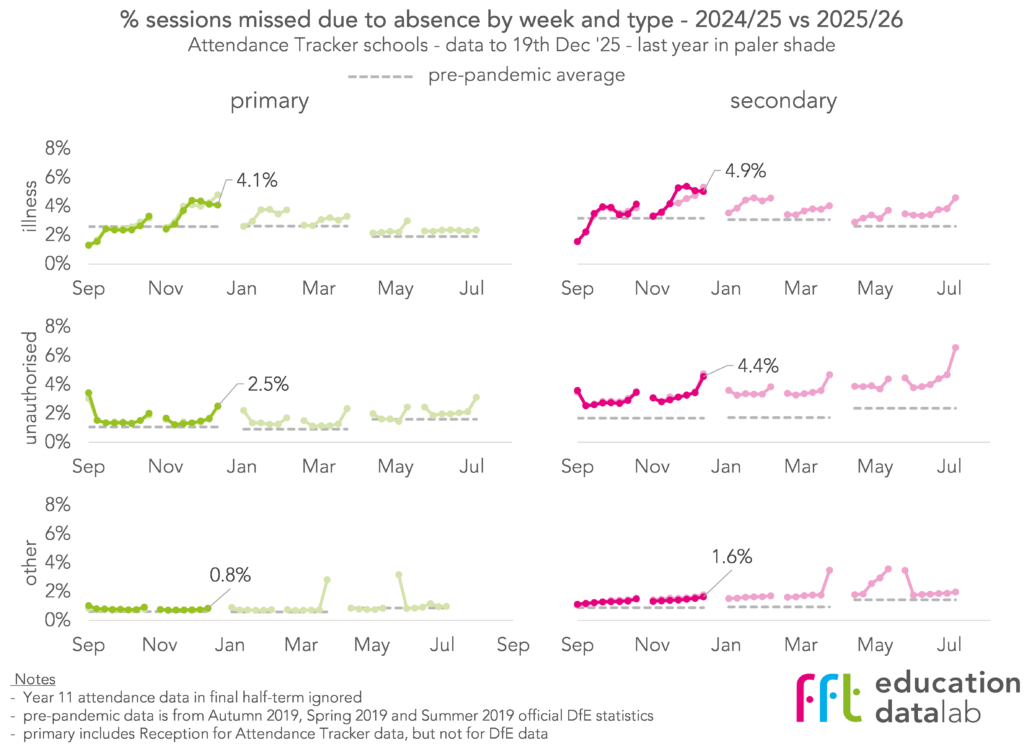

To get a better idea of what’s driving these patterns, we plot the same data, but broken down by the reasons for absence recorded in schools’ registers. We divide absence into three categories: illness-related, unauthorised, and other (where “other” covers any type of absence which the school has authorised but has not recorded as being illness-related, for example, medical appointments).

The patterns for unauthorised and other absence so far this year are almost identical to last year. Illness-related absence in the second half-term, however, looks different.

At both primary and secondary this year, illness-related absence increased rapidly through November, peaking in the first week of December, then fell in the run-up to Christmas. This is consistent with reports of an early flu season.

At secondary, the contrast with last year, where illness-related absence increased gradually through the term and peaked just before Christmas, is clear. It is less clear at primary, where there appear to have been two peaks last year: one at the end of November and a second in the week before Christmas.

Illness absence by region

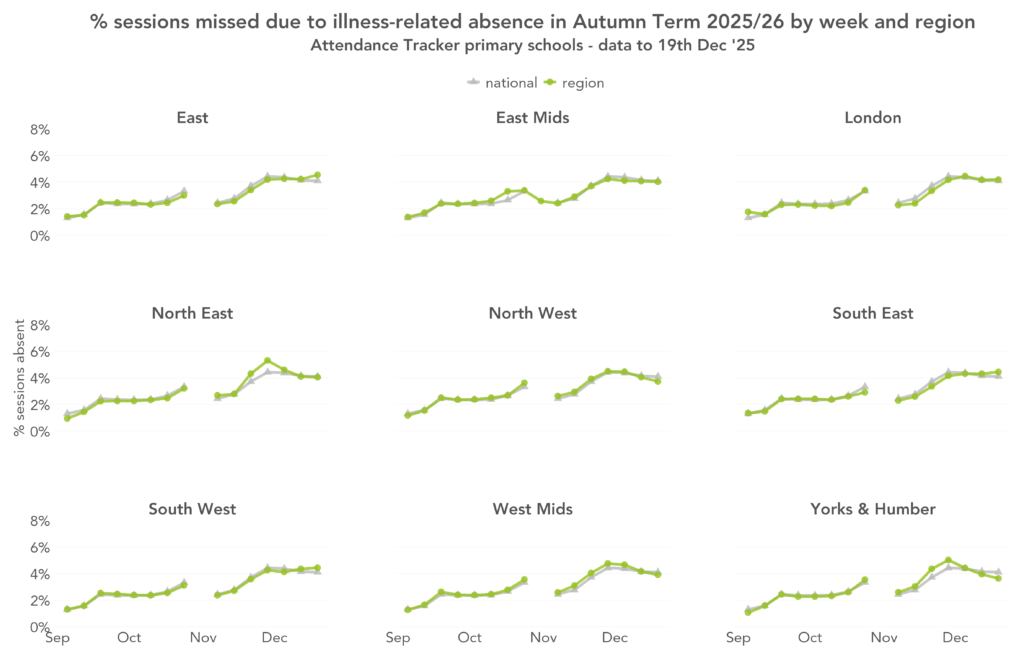

To see whether the early peak this year was a national phenomenon, or driven by certain areas, we plot the percentage of sessions missed due to illness-related absence by region, and compare with the percentages nationally. First, primary:

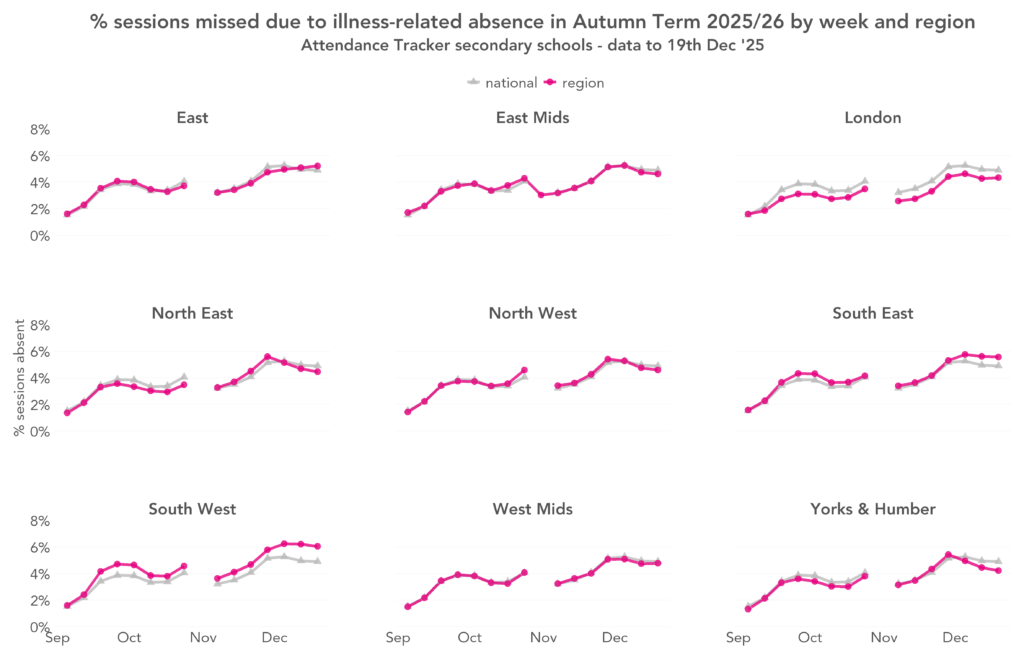

And secondary:

The national pattern is mirrored in most regions, though there are some differences. Firstly, at both primary and secondary, the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber saw more pronounced early December peaks than other regions. Secondly, the East of England was the only region without an early December peak at either primary or secondary. And thirdly, at primary, the South West and London saw rates of illness-related absence broadly in-line with national rates, whereas at secondary, rates in the South West were consistently higher than national and in London consistently lower, though the shapes in both regions were similar.

Illness absence post-pandemic

Let’s look at this year’s illness-related absence rates nationally in the context of the last few years, from 2022/23 onwards.

At both primary and secondary, the shapes of the graphs across the first half-term are broadly similar in each of the years, albeit rates were higher in the earlier years. In the second half-term, this year’s early peak does seem to be unusual, particularly at secondary.

Thankfully, none of the past three years have seen illness-related absences as high as Autumn 2022.

Absence by reason

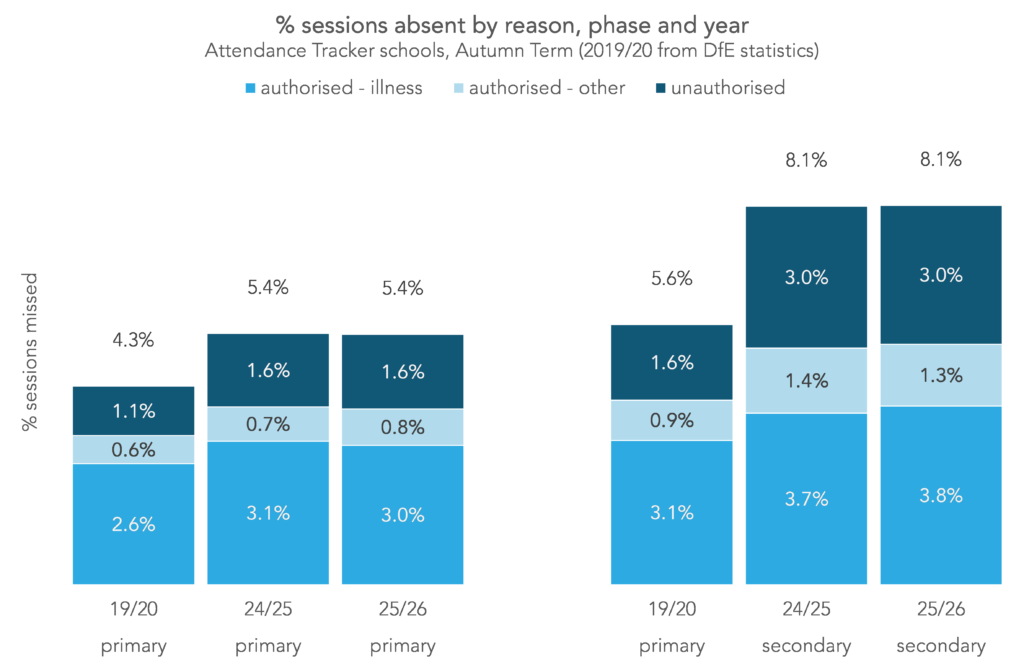

Next, let’s look to see whether the different pattern of illness-related absence this year have impacted the overall rates of absence across the term. Below, we plot the percentage of sessions missed this Autumn Term compared with last, and with Autumn Term 2019, broken down by the reasons recorded in schools’ registers.

Perhaps surprisingly, the earlier peak in illness-related absence this year hasn’t translated into a substantial increase in absence across the term as a whole.

There has been a small increase compared with last year in illness-related absence at secondary, but this has been cancelled out by a small decrease in absence for other authorised reasons. Unauthorised absence has remained unchanged.

At primary, the reverse is true. A small decrease in illness-related absence has been cancelled out by a small increase in absence for other authorised reasons.

Overall then, absence rates at both primary and secondary are unchanged since last year. The 5.4% of sessions missed by primary pupils is 1.1 percentage points higher than pre-pandemic (a proportional increase of 25%), and the 8.1% missed by secondary pupils is 2.5 percentage points higher (a proportional increase of 45%).

Persistent absence by region

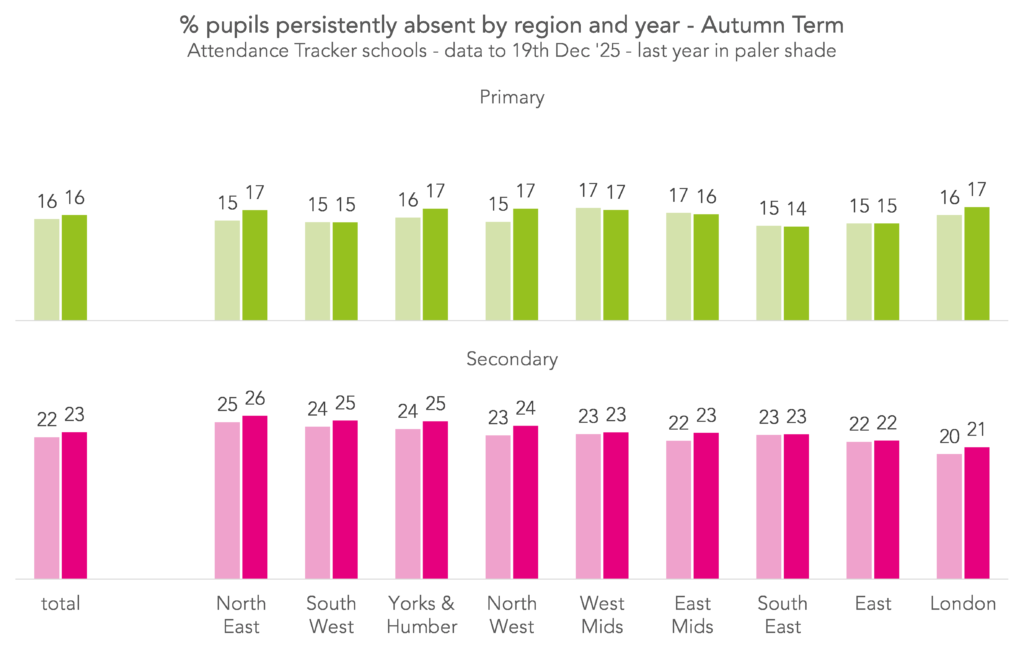

To finish, we’ll calculate the number of pupils who were persistently absent across Autumn Term this year, missing 10% or more of possible sessions. With Autumn Term approximately 15 weeks long, a pupil would need to have missed at least a week and a half of school to be considered persistently absent.

Below, we plot the percentage of pupils who have surpassed this threshold this year and last year, broken down by region.

Rates of persistent absence are broadly similar this year compared with last year. Where there have been changes, they have been small. The largest change by region was at primary in the North West, where there was a 2 percentage point increase.

There remains a wider range in persistent absence rates at secondary (26% in the North East to 21% in London) than at primary (17% in five regions to 14% in the South East).

The 16% of primary pupils classed as persistently absent is 5 percentage points higher than pre-pandemic (11% in Autumn 2019), and the 23% of secondary pupils is 8 percentage points higher (15% in Autumn 2019).

Summing up

Despite an unusually rapid increase in illness-related absence through November, particularly at secondary, overall rates of absence and persistent absence in this year’s Autumn Term were broadly similar to last year’s.

Pupil attendance remains a priority area for the DfE (signalled by the somewhat beleaguered launch of attendance reports for schools last term, for example). If there are to be any improvements in absence this year, they’ll need to come in Spring or Summer.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment