This blogpost forms part of a package of A-Level and GCSE results analysis, with funding received from the Nuffield Foundation. View our results day microsite, which shows national trends in entries and attainment for each A-Level and AS-Level subject. Data for 2018 will be available from 9.30am on 16 August.

This year’s A-Level results come out tomorrow. It will be a significant day in the lives of students getting their results.

But what might the national results show?

All change

There will be change, as usual.

This will affect the year-on-year comparability of the data as well as the comparability of the data between the three home nations, as Wales and Northern Ireland increasingly diverge from England.

In England, AS-Levels have now been decoupled from A-Levels in all subjects, and no longer contribute to students’ overall A-Level grades. We expect a further decline in AS-Level entries in England as results in the third and final wave of reformed subjects are awarded for the first time. This includes the hitherto most popular subject of all, mathematics. We wrote last year how entries in the first two waves of reformed subjects had plummeted, both as a result of the reforms but also as a result of funding constraints.

This latter reason could might also see AS-Level entries declining in Wales and Northern Ireland, even though they still contribute 40% to overall A-Level grades in those countries.

Results will be published for the second wave of reformed A-Level subjects in both England and Wales. These include French; German; Spanish; geography; drama; music; physical education; religious studies; and Welsh second language.

Reformed A-Levels offered by CCEA, the awarding body for Northern Ireland, will be awarded for the first time this year in almost all subjects. However, some students may still have taken unreformed subjects (or reformed subjects, for that matter) offered by one of the English awarding bodies.

We would not expect much change in attainment, however, even in reformed subjects. This is because of the approach Ofqual takes to maintaining standards over time known as comparable outcomes. Any changes in national results in A-Levels and AS-Levels (and GCSEs) will tell you more about changes in the prior attainment profile of students than changes in standards achieved.

What will happen to boys’ results?

Having said that, might we expect a dip in the attainment of boys in England as a result of the World Cup? Two years ago we wrote about how success in the European Championship might have affected the results of boys in Wales (and research suggests it is boys who are more affected).

Last year there was much discussion about the attainment of boys at A-Level when it was reported that the percentage of A*-A grades achieved by boys at A-Level exceeded the percentage of girls for the first time in nearly twenty years.

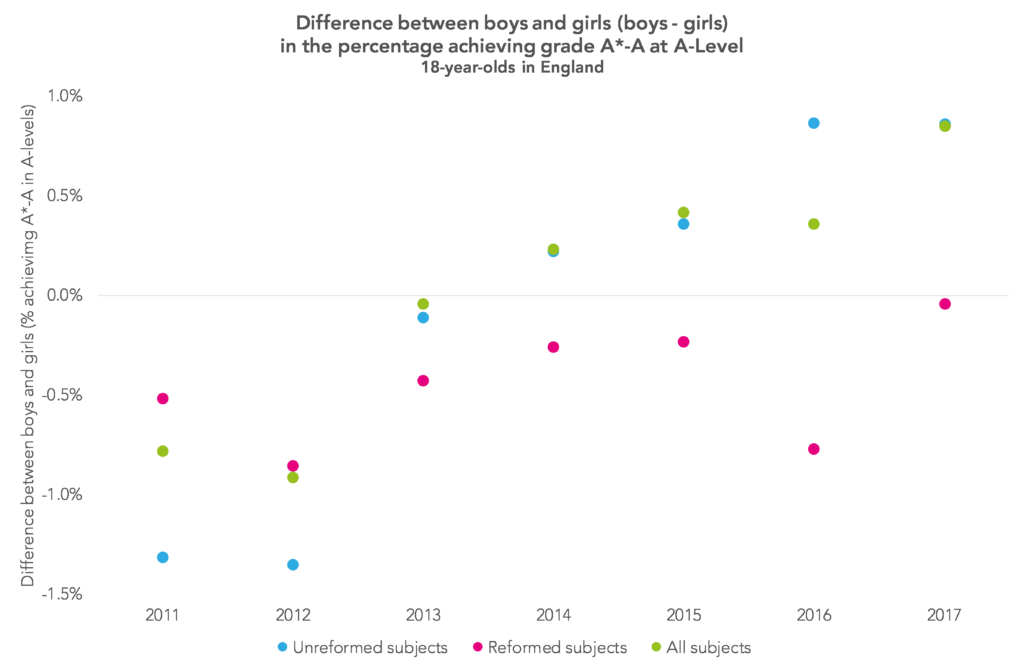

One possible explanation was that the newly reformed A-Levels in England, which are generally based on final assessment, favour boys over girls. However, this overlooked the fact that the gap between boys and girls had been closing before the reforms were introduced.

If we consider just 18-year-olds in England, using data from the National Pupil Database we see that the attainment of boys at grades A*-A overtook that of girls back in 2014[1].

But in the reformed A-Levels which were first awarded in 2017, the attainment of boys and girls was virtually identical. As the chart below shows, the gap closed markedly from 2016, but that followed a sharp drop compared to 2015. It also shows a drop in 2012. Coincidentally or not, major international football tournaments were held in both 2012 and 2016.

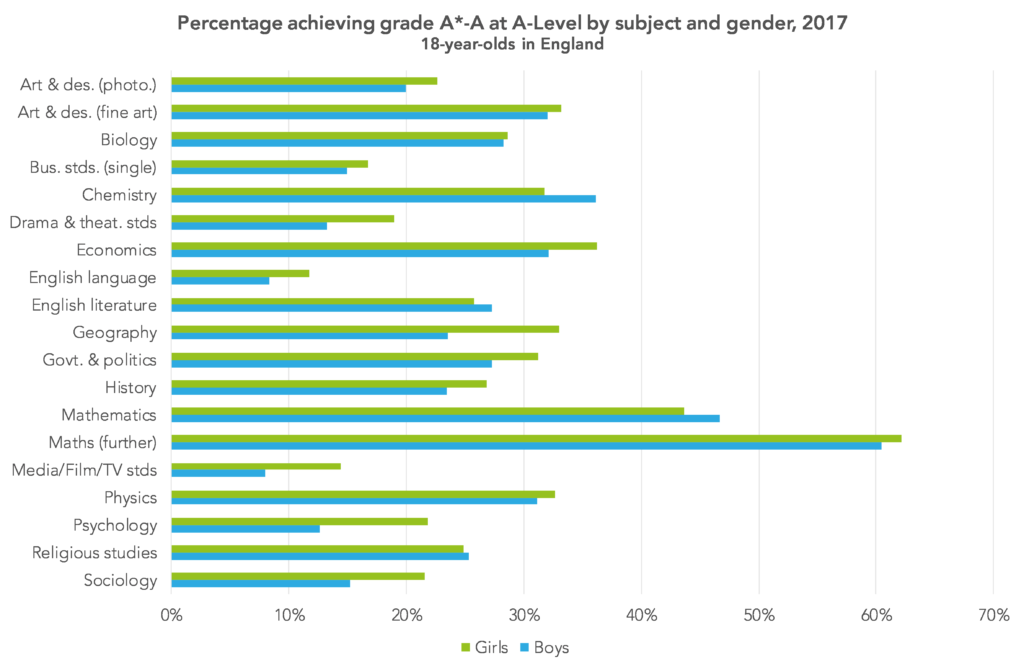

However, in 2017 boys held an advantage over girls in only a small number of subjects. Among the 19 major subjects (those with more than 10,000 entries in 2017), a higher percentage of boys achieved grades A*-A compared to girls in just four: chemistry, English literature, mathematics and religious studies.

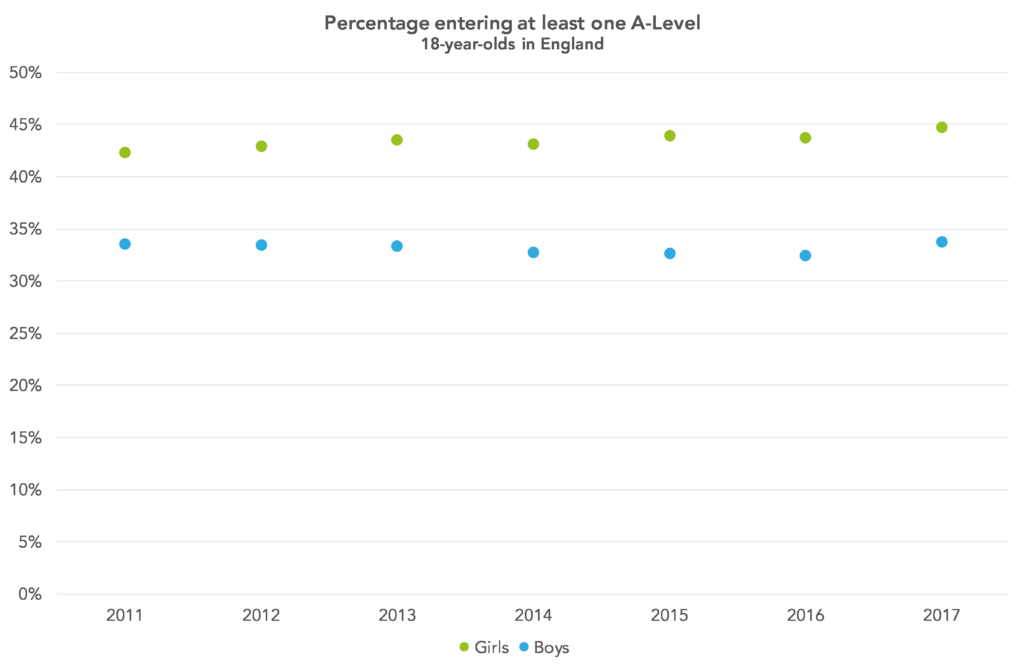

Of course, all of this ignores the fact that girls are more likely to enter A-Levels than boys, which is due at least in part to higher levels of attainment at Key Stage 4. The chart below shows the number of 18-year-olds in England entered for at least one A-Level as a percentage of the national cohort of 16-year-olds two years earlier. The gap in A-Level entry between girls and boys has widened slightly over the period observed.

This blogpost forms part of a package of A-Level and GCSE results analysis, with funding received from the Nuffield Foundation. View our results day microsite, which shows national trends in entries and attainment for each A-Level and AS-Level subject. Data for 2018 will be available from 9.30am on 16 August.

1. Numbers based on National Pupil Database data will differ a little from those in JCQ (Joint Council for Qualifications) releases, as the JCQ figures available on results days are provisional data.

Leave A Comment