Now that the dust is settling somewhat on this year’s GCSE and A-Level awarding process we have a final set of results – newly in the case of GCSEs; in replacement of results awarded last week in the case of A-Levels.

So what do they show?

GCSEs

Overall, GCSE results are up sharply – 78.8% of entries received a grade 4 or above this year, compared to 69.9% last year. (The figures we’re reporting here are for 16-year-olds in England.)

At grade 7 or above, there was a jump from 21.9% to 27.6%.

The charts below shows how things have changed in every subject.

The overall change masks considerable variation between subjects.

Results in some large-entry subjects – English literature and maths, for example – have increased by slightly more modest amounts.

Much larger increases have been recorded in some other subjects though, as the chart below shows. (Some, though not all, of these are smaller entry subjects – computing, design and technology, business studies and PE all have decent numbers of entries.)

You’ll note that results increased by the smallest amounts at the grade 4 or above threshold in the single sciences. That’s due to the single sciences typically being entered by higher-attaining pupils – the average grade in each of biology, chemistry and physics was already around the grade 6 mark last year, so there’ll be relatively few pupils receiving a grade 4 this year who wouldn’t have done so last year.

Ofqual has also confirmed that a planned (small) uplift was made in the mix of grades that its standardisation process came up with in French and German, fulfilling a commitment that it had made previously, to bring grading closer in line with GCSE Spanish. While many students will have received their centre assessment grade as opposed to a grade generated by the standardisation process, this will have helped some pupils.

The regulator has also this morning reported the results of the National Reference Test – conducted before the coronavirus crisis shut schools. This led Ofqual to conclude that standards in maths had improved versus the 2017 baseline – and as such, the mix of grades generated by its standardisation process was raised slightly. Again, the fact that pupils have ended up being awarded the higher of their centre assessment grade and their algorithmically-generated grade means this may well have had quite limited effect in practice, but some pupils will have benefited.

We’ll update this post with more details as the day goes on.

A-Levels

A-Level results are also up – and to a greater extent, if anything.

At the grade C or above threshold, results are up from 75.5% to 87.5% across all subjects. At grades A*-A, there was an increase from 25.2% to 38.1%. (Figures here are for students of all ages in England.)

The charts below shows how things have changed in every subject.

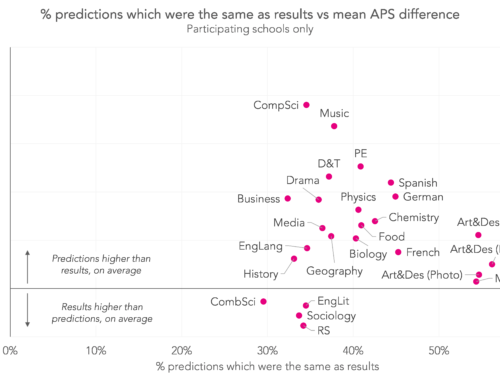

At the top end of the grade distribution, small entry subjects still seem to have come out favourably – with languages and music recording some of the biggest increases in results (as they did when the first iteration of A-Level results came out last Thursday), as the chart below shows

We can also look at how today’s results differ to last week’s, when students were given out A-Level results that leant heavily on the standardisation algorithm. This gives an indication of how much change has been introduced by using centre assessment grades in place of those calculated by the Ofqual model.

As we would have expected, those subjects with typically small numbers of entrants at each centre, such as German and music, have seen results increase the least following the change in approach. This is due to a higher proportion of centre assessment grades already being included in the results handed out last week in these subjects.

We’ll update this post with more findings as the day goes on.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Thanks for sharing this very useful insight.

I wonder if the small subject size variation is down to the fact that is not possible to forecast accurately (CAG or algorithm) based on small data sets? Conversely where larger data sets exist is it likely that more accurate predictions can be made with any variances likely to be around the tail end of distributions?

Thanks, Adrian. I’m not sure is the honest answer – I’m sure this is one of the things that will be picked over in the coming weeks and months.

Thanks for the data – fascinating. Do you have any figures for the number of students gaining 7 or more grade 9s, compared to 2019?

We don’t, I’m afraid Peter. For probably understandable reasons that’s not a figure that Ofqual have put into the public domain this year – and we’d not be able to work it out until some way into the next academic year, when we get access to pupil-level data.

Thanks for this.

I’m just wondering about a comparison for the A levels against more than just 2019 given the variation between years? I recall reading somewhere that 2019 was a relatively poor cohort at A level? Might give the apparently elevated levels this year more context?

That’s a fair point, Vicky. In 2019, 75.5% of A-Level entries in England were awarded a C or higher – down each year since 2016, when the figure stood at 77.5%. (2019 was also a low at grade A or higher, though there hasn’t been quite such a consistent trend.)

So, that makes a bit of a difference – comparing to 2016 there’s a 10 percentage point increase in A*-C rates, versus the 12 percentage point increase on last year’s results.

This result has already been issued to the students….now you must concentrate towards oct nov exams with all of this pendamic and stuff we are so confused that rather oct nov exams will be held or not only one month is remaining there are many students all over the world who are studing by there own without any teacher without any online calsses this is so difficult for us to manage hope that you’ll make a better decision for us

I would like to highlight the fact that some good students, especially from selective state schools,

have suffered grade deflation in this year’s GCSE results. This is due to the fact that schools were told to maintain grade parity over time.

As a tutor myself, I have come across students who were predicted an 8C by the school, scored an 8B in mock and yet awarded a 7 in the final results. I think this is a function of grade-parity which schools were asked to maintain by Ofqual.

Say, the average number of A*s achieved by the students of a school in Maths over a period of three years is 30. Now to maintain parity with 30, this year’s cohorts were deprived because the 31st, 32nd, 33rd….. students could also have achieved A* if normal exams were held and depending on their performance during the exam. However, to maintain normality with grade parity of 30, they were deprived of an A* and may be pushed to an A,despite being capable of getting an A*.

This factor is being overlooked and it is affecting mostly the cohorts in selective state schools and particularly in subjects with more students like Maths, English and Sciences. In selective state schools the number of able students are more compared to comprehensive schools and hence they are negatively impacted by the grade parity phenomenon.

Please investigate the matter and highlight it for the benefit of the affected students.

Kind regards,