A-Level results are out on Thursday. As always, we’ll be posting commentary on the day. If you don’t want to miss anything, make sure you sign up now to receive our analysis as it comes out.

But if you can’t wait, here’s a round-up of what we’ll be looking out for on the day.

Grades will fall compared to last year

It’s hardly news at this point to say that we’ll see lower grades this year compared to last year.

Most people reading this post will be painfully familiar with why this is, but here’s a quick recap for anyone who is not aware. In both 2020 and 2021, public exams were cancelled due to the pandemic, and different systems of grading, known as Centre Assessed Grades (CAGs) and Teacher Assessed Grades (TAGs), were temporarily used. This resulted in higher grades being awarded than in typical years.

Last year, grades were adjusted to a point within the 2019 to 2021 range.

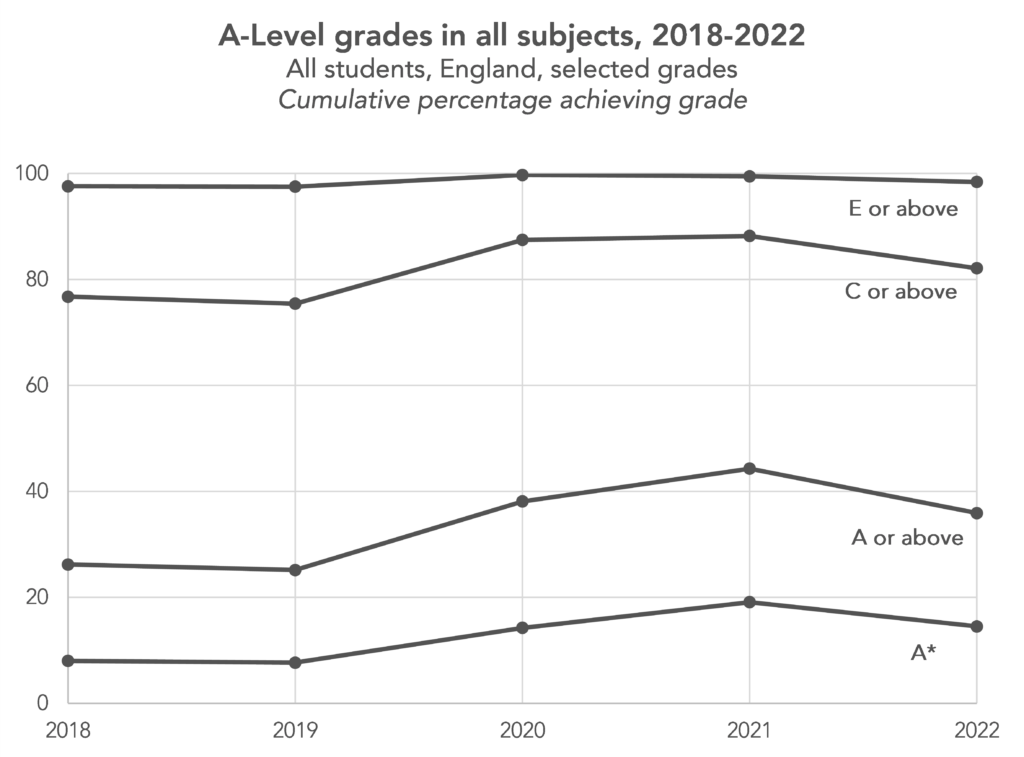

To see what that looks like, here are the grades across all subjects from 2018-2022.

This year, grades will be adjusted to bring them in line with 2019. As a result, we will see lower grades this year than last year. Reports have suggested we could see as many as 100,000 fewer A and A* grades awarded this year compared to last year.

Some subjects will see a harsher fall in grades than others

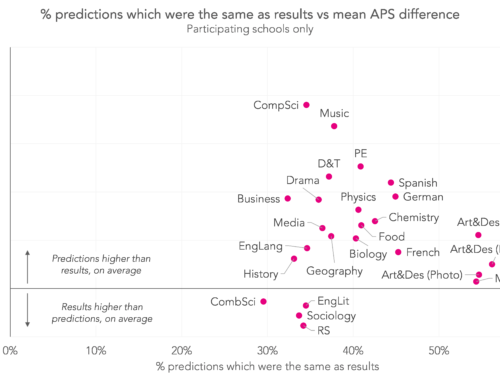

As mentioned above, Ofqual’s policy was for grades last year to sit at the midpoint between 2019 and 2021. But, as shown below, this didn’t appear to be the case when things were broken down by subject.

The grades for some of the most popular A-Level subjects – biology, chemistry and maths – were slightly below the midpoint, but most other subjects were above it.

So this year, we expect that grades in biology, chemistry and maths won’t fall as much as those in other subjects compared to last year. And some other subjects may see particularly sharp falls in grades.

The disadvantage gap will probably widen

While we’re not expecting any figures to be published on results day, it’s quite likely that the disadvantage gap in grades will widen again this year.

Last year’s gap was the widest since records began, at least partly owing to disadvantaged students being disproportionately affected by the consequences of the pandemic.

For example, as we’ve shown repeatedly, disadvantaged students are more likely to have missed a lot of school during the course of the pandemic, and beyond, than their peers. While we’ve not looked at the figures for post-16 students, we did look at the figures for this year’s A-Level cohort back when they took their GCSEs in 2021 – and found that they missed than a fifth of sessions, 50% more than their peers.

We should note though that the disadvantage gap in A-Level grades is only part of the picture. Disadvantaged students are less likely than their peers to choose to study A-Levels in the first place. This is at least partly because of the disadvantage gap in grades at GCSE: disadvantaged students are less likely to have the grades required to enter A-Levels, particularly those that require top GCSE grades.

And that’s where things might get interesting this year. This year’s A-Level cohort took GCSEs in 2021, when grades, awarded via TAGs, were higher than in a typical year. So a higher proportion will have met the entry criteria for A-Levels than usual, and we might expect to see more students choosing A-Levels than usual.

We don’t have the figures yet, but these unusual circumstances might well mean that a higher proportion of disadvantaged pupils went on to enter A-Levels this year than in a typical year. Which makes comparing the disadvantage gap across years a bit more complicated than usual.

The gender gap in grades will narrow

One side effect of CAGs and TAGs that perhaps isn’t discussed as much as others is the widening of the gender gap in grades.

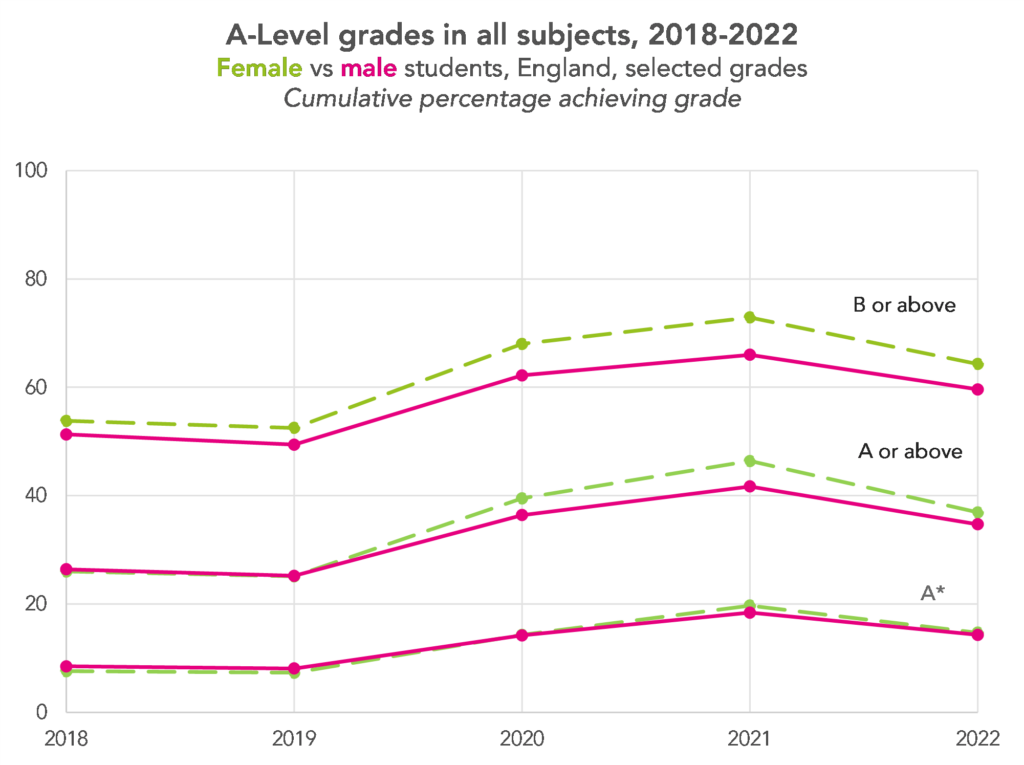

The chart below shows the proportion of male and female students achieving top grades across all A-Levels over the last few years.

Pre-pandemic, the gender gap was small: in 2019, 25.1% of A-Levels taken by female students received grade A or above, compared to 25.2% of male students, a gap of just 0.1 percentage points.

The gap widened in 2020 and 2021, increasing to 4.7 percentage points in 2021, but fell back to 2.2 percentage points in 2022. We expect it to fall again this year.

Entry numbers will increase… but not in modern foreign languages

According to Ofqual’s provisional entry figures, we’re expecting a 2.3% increase in entries compared to last year. This is partly explained by an increase in the population of 18 year olds, but only partly: the increase in population is just 1.5% according to ONS population estimates.

We may be seeing an increase in A-Level entries because more students achieved the required GCSE grades via TAGs in 2021 than might be expected in a ‘typical’ year.

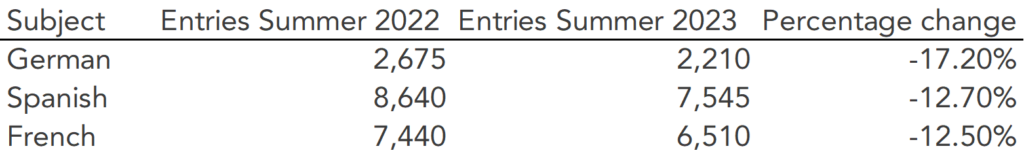

But entries in some subjects are expected to fall, particularly in modern foreign languages: the three subjects with the largest expected fall in entries are Spanish, French and German.

This is part of a longer term fall in entries in French and German, which seems unlikely to change anytime soon given that entries to modern foreign languages at GCSE seem to have stalled, despite their inclusion in the EBacc.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Why no mention at all of the 324,000 students recieving a grade for their vocational and technical qualifications?

More on this tomorrow. But (briefly) part of the reason we/ journalists/ everyone else talk about vocational and tech quals less than A-levels around results days is simply that less data is published. Compare what JCQ produce for A-level with data for vocational and tech quals. As the year goes on we get to work with the underlying data ourselves and so can produce a more rounded picture. But not on results days.