When this year’s GCSE results came out, we were surprised to see that entries to Spanish had fallen. We’d actually predicted – based on provisional data – that they’d increase, and that entries to languages overall would be up.

This got us thinking about trends in entries to GCSEs in modern foreign languages, and here we’re going to take a look back what entry numbers have looked like over the last few years.

Languages and the EBacc

Back in 2017, the government set a target (or ‘ambition’ as they termed it) for 75% of pupils to take the English Baccalaureate by 2022. That might have seemed a reasonable ambition when it was set, but things aren’t looking hopeful now. EBacc entries numbers for this year haven’t been published yet, but last year they stood at just 39%.

And we know that the reason the target is so far away because not enough pupils are studying languages. We’ve written before about the possible reasons for this – a lack of language teachers and harsher grading for languages GCSEs are among them.

But has the situation been improving in recent years?

Trends over the last five years

As a reminder, the EBacc consists of five ‘pillars’: English, maths, science, humanities and languages. English, maths and science are compulsory in schools and more than 95% of pupils enter GCSEs in these subjects. Humanities and, of course, languages are entered by fewer pupils.

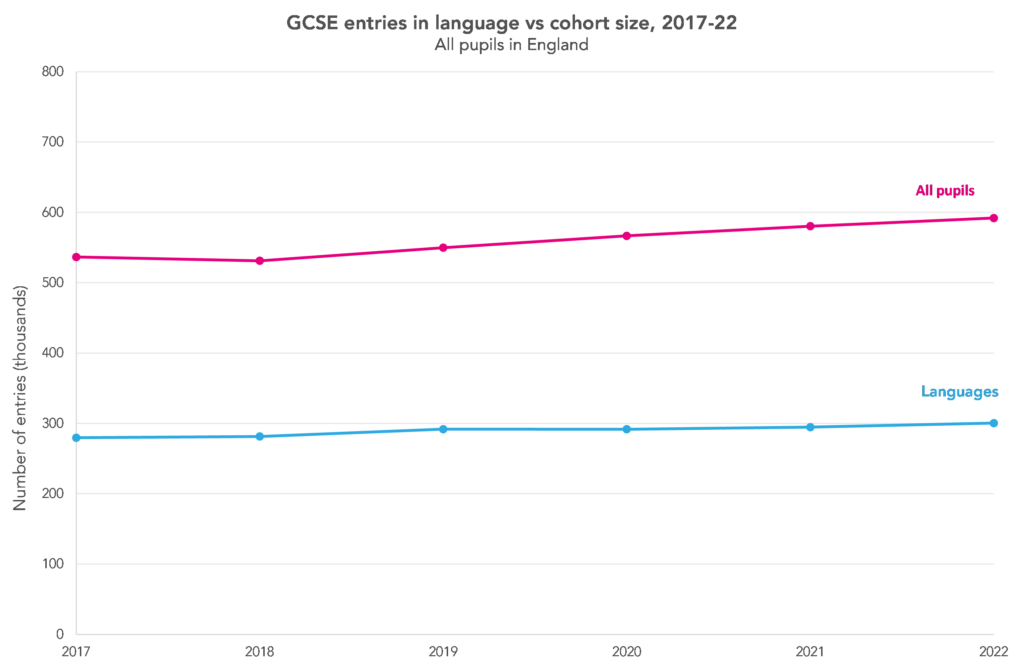

The chart below shows how entries to GCSEs in modern foreign languages relate to entries to the EBacc.[1] We also include the proportion of entries to the humanities subjects for reference.

The trends in EBacc entries almost exactly track the trends in entries to languages. While the proportion of pupils entering humanities subjects has been increasing over the last few years, this has had little effect on the overall proportion entering the EBacc.

It really does all come down to languages. And the proportion of pupils entering the languages pillar of the EBacc is falling.

Let’s take a brief look at what this means in terms of entry numbers.

First of all, we should note that the population of KS4 pupils has increased over the last few years – so we would expect entries to languages to increase even if they haven’t become more popular.

But – in short – they have not become more popular.

The chart below shows how entries in modern foreign languages compare to the overall number of pupils in Year 11.

Entries to modern foreign languages have increased, from 279,709 in 2018 to 300,402 this year. But the cohort size has also increased, and rather more sharply.

Which MFL subjects are pupils studying?

The most popular modern foreign language at GCSE is French, followed by Spanish and German. In the next chart, we show the trends in entries for these three subjects, and for other modern foreign languages, since 2017.

French has more or less flat-lined which means, given the increase in pupil population, that it’s become less popular. German has also fallen in popularity, while entries to Spanish rose between 2018 and 2021, before falling slightly this year.

We also noticed that entries in Spanish were 8% lower in the JCQ data published yesterday compared to Ofqual’s provisional data for Summer 2022 entries published at the end of May. This suggests that slightly more pupils studied languages during Key Stage 4 but were then ultimately not entered for examination for whatever reason.

Interestingly, the entries to other modern languages, which were flat until 2020, took a fall during the pandemic. This appears to be because of a decrease in pupils studying community languages, such as Bengali, Polish and Turkish, which are often taught outside school. The restrictions during the pandemic and the cancellation of exams meant that many pupils were unable to enter GCSEs in these subjects. Entry numbers this year are up on pre-pandemic levels.

Teacher recruitment

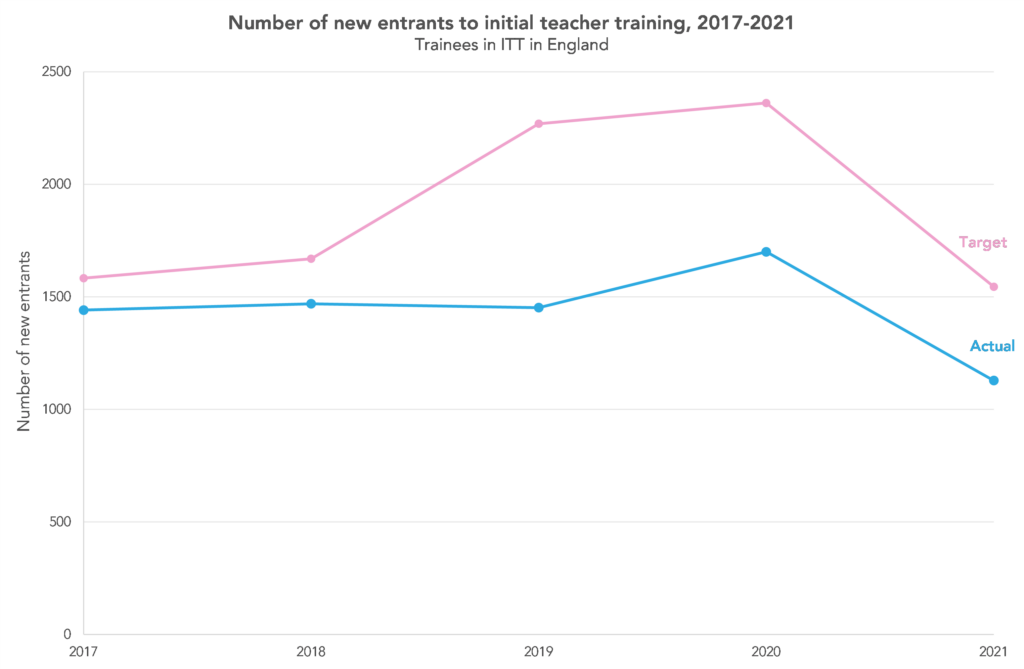

We mentioned above that one reason for low entries into MFL is a lack of language teachers. So let’s take a look at whether that situation is likely to improve.

The chart below shows the recruitment targets, and actual numbers recruited, over the last five years.

There was a bit of a boost in numbers in 2020, although the number of ITT entrants still fell well below the target. Last year, the target was quite drastically reduced – by 34% – and still wasn’t met.

The reduction of the target, despite the shortfall in previous years, does seem to suggest that the government’s commitment to increasing the number of MFL teachers is lukewarm at the very best.

Reforms to grading

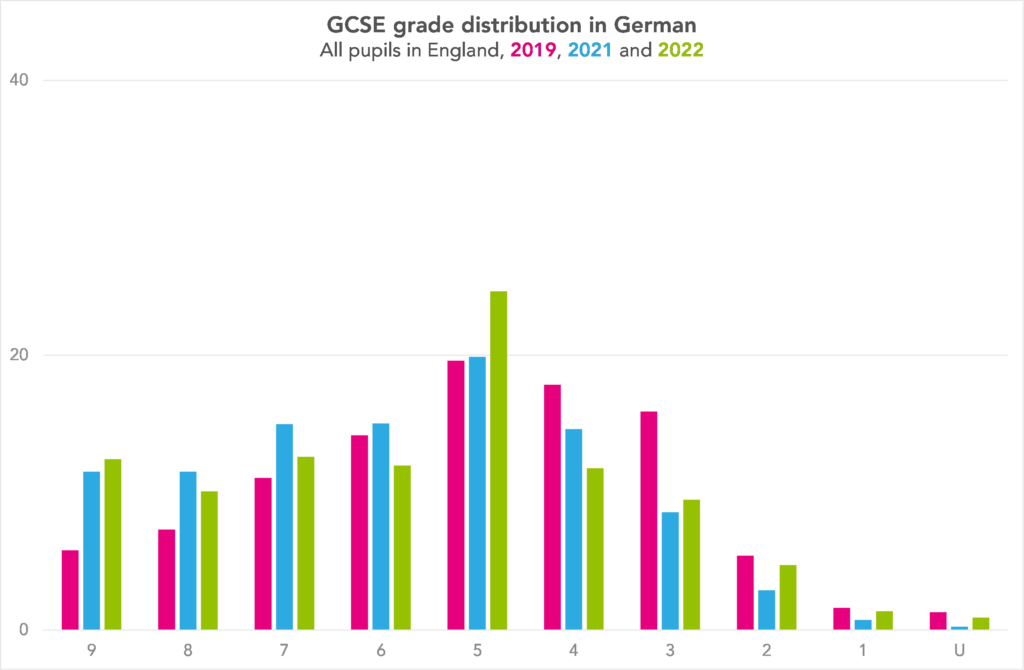

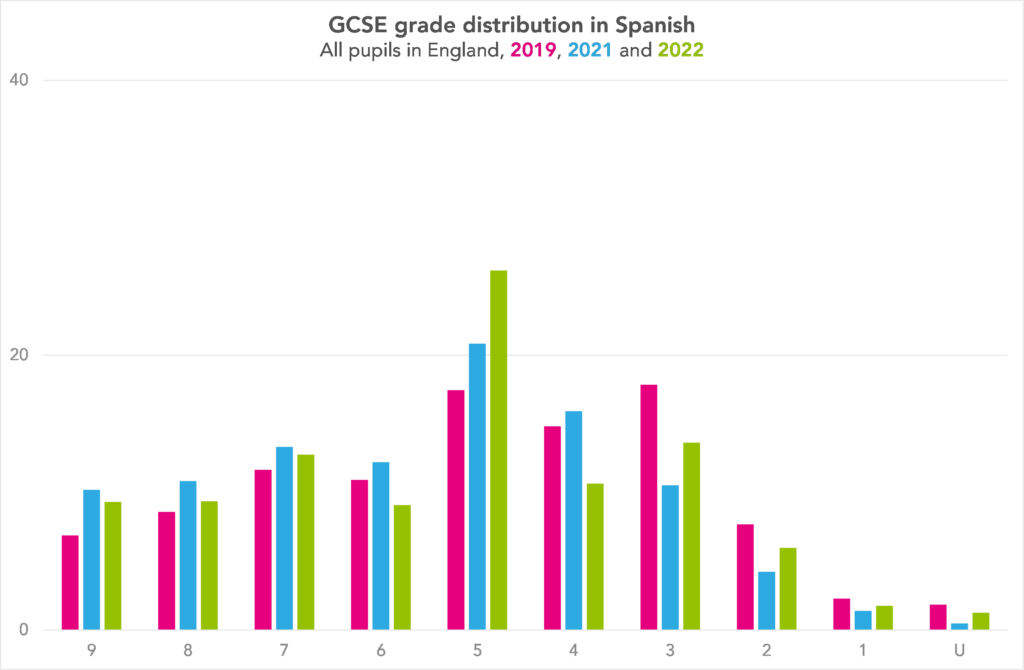

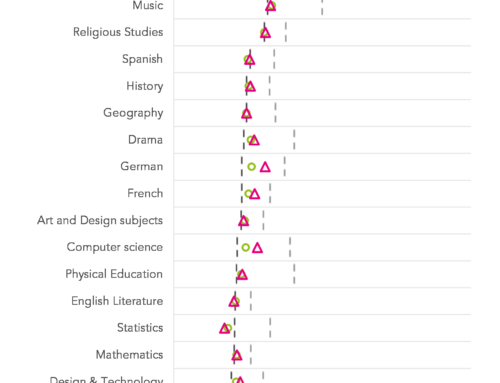

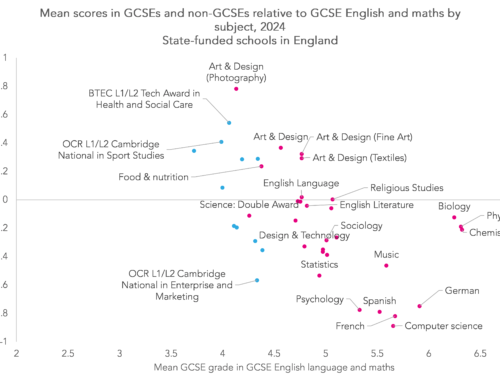

Finally, just a brief mention of grading. It’s long been argued that modern foreign languages are graded more severely than other subjects at GCSE.

In 2019, Ofqual announced that the grading standards in French and German – but not Spanish – would be adjusted from 2020 in an attempt to rectify this. We argued at the time that this change did not go far enough, and would still leave MFL (including Spanish) more severely graded than other subjects.

As things turned out, the pandemic intervened and grades in both 2020 and 2021 were not determined by public exams. Adjustments were applied for the first time this year, but the prospect of less severe grading does not appear to have encouraged more pupils to enter French and German.

The charts below show the distribution of grades has changed from 2019 to 2021 and 2022 in French and German. We also show Spanish as a comparison in which adjustments to correct for grading severity have not been applied.

In both French and German, the proportion of grade 9s has actually increased slightly from 2021, while in Spanish they have fallen. In all three subjects, grade 5 was the clear modal grade in 2022.

Some final thoughts

There are some small causes for optimism here. The dip in the proportion of pupils entries for community languages reversed this year. And we might expect French and German to become (slightly) more attractive options now that Ofqual’s reforms to grading standards have kicked in.

But there are also some real causes for pessimism, particularly the teacher recruitment figures. It certainly doesn’t look like GCSE entry numbers are going to shoot up drastically any time soon. Which means that anyone hoping that we’ll manage to realise the ambition of 75% of pupils taking the EBacc in the next few years has very little reason to feel optimistic.

- GCSEs in ancient languages also count towards the languages pillar of the Ebacc, but these account for a low proportion of entries.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Brexit could be a big factor in lower MFL teacher recruitment.

Would be interesting to look at time dedicate to language teaching across the age range. My daughter just started secondary school, and at the school she is at, they have 2.5 hours of Spanish per week, but at another local school, it’s just 1 hour. If that’s all the language teaching you get in year 7, GCSE will be almost certainly unachievable.

Hi Jeremy, yes indeed that would be interesting. Not least because there are likely quite a lot of schools that are unable to offer any hours at all.