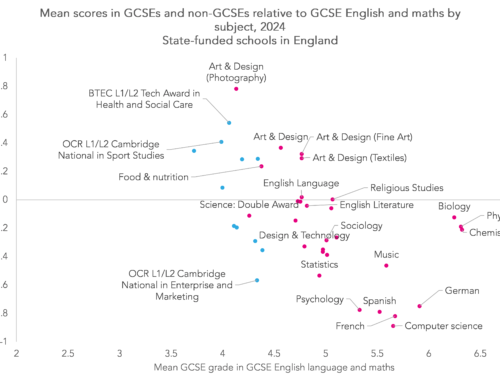

Last week we published a blogpost asking whether some qualifications are more generously scored in secondary school performance tables.

We found that GCSEs in French, German and Spanish were among the least generously scored compared to English and maths.

Ofqual announced last year that it would be looking into inter-subject comparability in GCSE modern foreign languages (MFL) and would be reporting this term.

It is probably about time that something was done.

Why are some subjects graded more severely?

In its analysis of the severity of grading in A-Level MFL, Ofqual makes the point that differences in apparent grading severity between subjects can arise due to factors such as student motivation, teaching quality, teaching time and so on.

In addition, as a 2008 report from Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring at Durham University pointed out, in some subjects, such as art and design, we do not know how representative entrants are of all pupils who enter a subject. If all 16-year-olds had to take art GCSE would it look so generously scored?

These are all fair criticisms of the sort of statistical comparison we made in our blogpost.

The problem is that it is at best difficult to get a handle on the impact they may have using the sort of observational data Ofqual and the awarding bodies have access to.

But for GCSE MFL, we can deal with the representativeness issue to some extent by going back in time when many more pupils were entered.

How difficult was MFL in 2004?

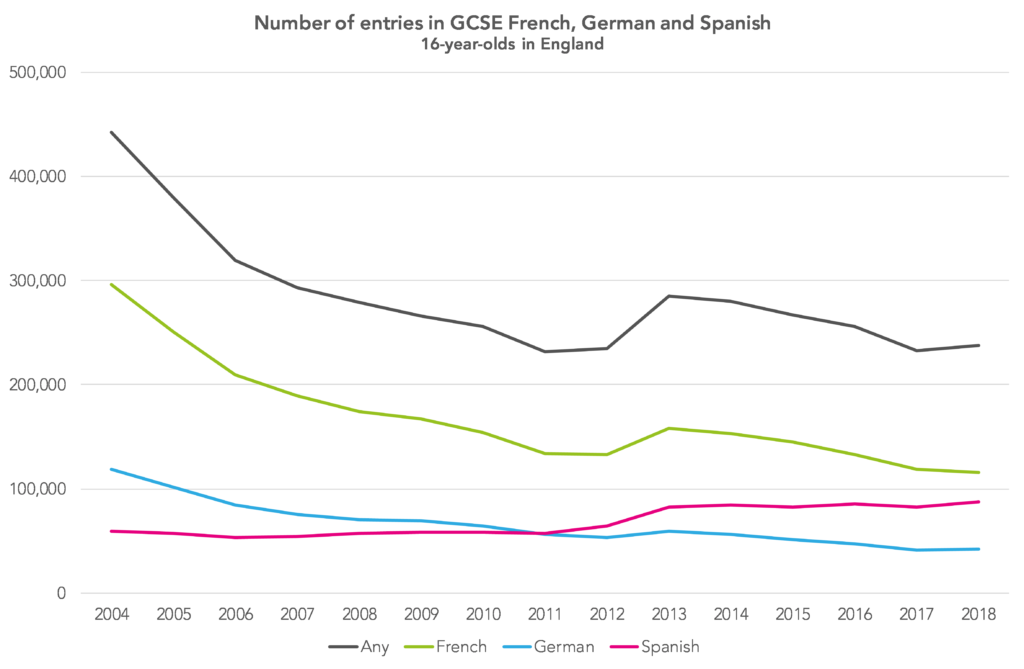

Modern foreign languages at Key Stage 4 ceased to be compulsory from September 2004. The effect on the numbers of GCSE entrants is shown clearly in the following chart.[1] Even the introduction of the English Baccalaureate (2011) hasn’t done much to reverse its decline.

In 2004, almost 70% of 16-year-olds in England entered a GCSE in a modern foreign language. This subsequently fell to just 41% in 2018.

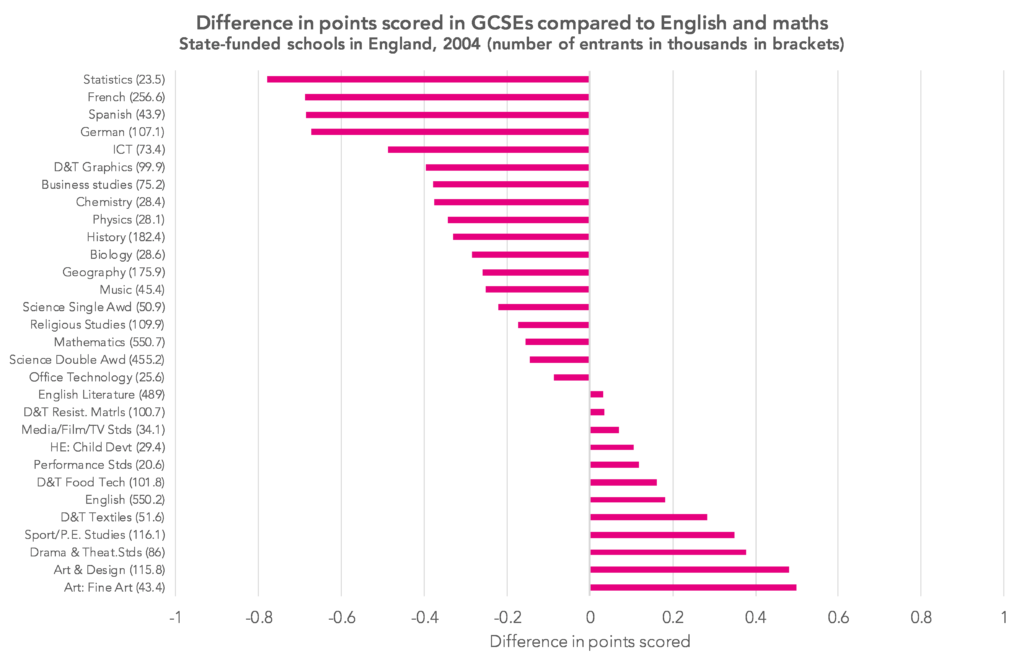

We can now look at severity of grading in 2004 in a range of subjects using the same method as in the previous blogpost, which looked at 2018 – that is, grades in different subjects are compared to the average of pupils’ English and maths results.[2]

The chart shows that French, German and Spanish were graded more severely back in 2004 when MFL was still compulsory. Many more pupils took GCSEs then compared to now yet grading severity looks about the same.

In fact, as the Durham University report noted in its literature review, they were graded more severely back in 1974 as well.

This suggests that severity of grading in MFL nowadays probably isn’t the result of a lack of representativeness among entrants. It looks like a historical quirk.

Will anything be done about MFL?

The issue of grading severity in GCSE MFL has been known about for some time.

QCA, a forerunner of Ofqual, investigated grading in 2008 but decided not to make any adjustments to grades. It advised that “instead we should focus on improving levels of teaching and learning in modern languages in order to gain students’ commitment and raise performance.”

If anything happened as a result of this advice, it doesn’t look like it has had much effect.

Perhaps its now time to hit reset on MFL grading.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. Only full course GCSEs are included. International GCSEs are not included.

2. If comparing to the 2018 chart in the previous post, bear in mind that the chart below is based on A*-G grades rather than 9-1. This changes the scale used for points scores.

I teach GCSE Japanese in a deprived inner city state school. I am well aware that while there are similar schools offering Japanese, the majority of candidates for GCSE Japanese are likely to be , a native speaker, or attend a selective school or attend a private school. This year 65% of students who took Japanese score 7-9 (grade 9 was 35%) and I do wonder if even within all the languages, some are graded more severely than others.

Link issue: The link to the graph for 2018 under the 2004 graph links to the comparison between different exam types rather than the the comparison between different subjects. Does the new regime of progress 8 allows for all candidates getting lower in Modern languages or is that element of progress 8 linked to ALL Ebacc subjects, hence affecting those that include a language in their Ebacc pot? I suspect different methodologies for the IDSR languages section and the school/ pupil P8 calculation?