Results for GCSEs and other Level 2 qualifications are out next week. As usual, we’ll be posting our analysis throughout the day on Thursday.

We’ll also be running a free webinar in the afternoon of results day where we’ll bring you some key insights live. You can sign up here.

To whet your appetite, we’ve put together a list of some of the things we’ll be looking out for.

1. All about the basics

Sign up to our newsletter

If you enjoy our content, why not sign up now to get notified when we publish a new post, or to receive our half termly newsletter?

Pupils receiving their GCSE results this year are the first group of pupils whose entire secondary education has been impacted by the pandemic (and, arguably, the group with the most disrupted primary to secondary transition).

They are also the first of two cohorts who are missing Key Stage 2 data, their tests having been cancelled due to the pandemic.

With no Progress 8 scores available, we think there may be a renewed interest in the “basics” – the percentage of pupils achieving grades 9-4 in English and maths. Schools will be able to calculate this for themselves on results day, but we’ll have to wait until at least October for the national figure to be released by DfE.

What we will have access to on results day though, are results in the separate qualifications of English language, English literature, and maths. Usually quite stable from year to year, we’ll be particularly interested in whether there are any changes in English. Last year, the national reference test (NRT) – intended to inform the setting of key grade boundaries in these subjects – showed that performance in English had dropped. Ofqual declined to make any changes, and the percentage of pupils achieving 9-4 in English remained broadly stable.

If the NRT shows another fall, might we see grade boundaries shifted, and a lower percentage of pupils reaching these key thresholds?

2. Grading in other subjects

Another question raised by pupils having no Key Stage 2 data is how and whether Ofqual intend to replace the comparable outcomes framework.

In a nutshell, Ofqual’s job is to maintain standards so that a particular grade in a particular subject “means” the same thing from one year to the next. The starting point of this process is usually to check whether this year’s cohort is different from last year’s in terms of prior attainment. If so, then grade boundaries will initially be set so that the distribution of pupils by key grades is similar to the previous year. This is what we mean by “comparable outcomes”. Exam boards are then free to change these, with evidence, if they think that the standard of work is better or worse than suggested around a particular boundary. (This latter point is important, particularly to Ofqual, who are sometimes accused of setting pre-determined “quotas” of grades.)

With no prior attainment data available to make these initial judgements, will Ofqual just use last year’s grade distribution as the starting point for every subject? What impact will this have? For example, will smaller subjects, typically more variable in their results from year to year than larger subjects like English and maths, see more stability than usual?

3. Entries down overall, but up in some subjects

One thing we get a bit of a steer on before results day is the number of entries in each subject, as Ofqual publish provisional entries in advance. These don’t take into account any late withdrawals, but the trends tend to hold when we find out the actual number of entries on results day.

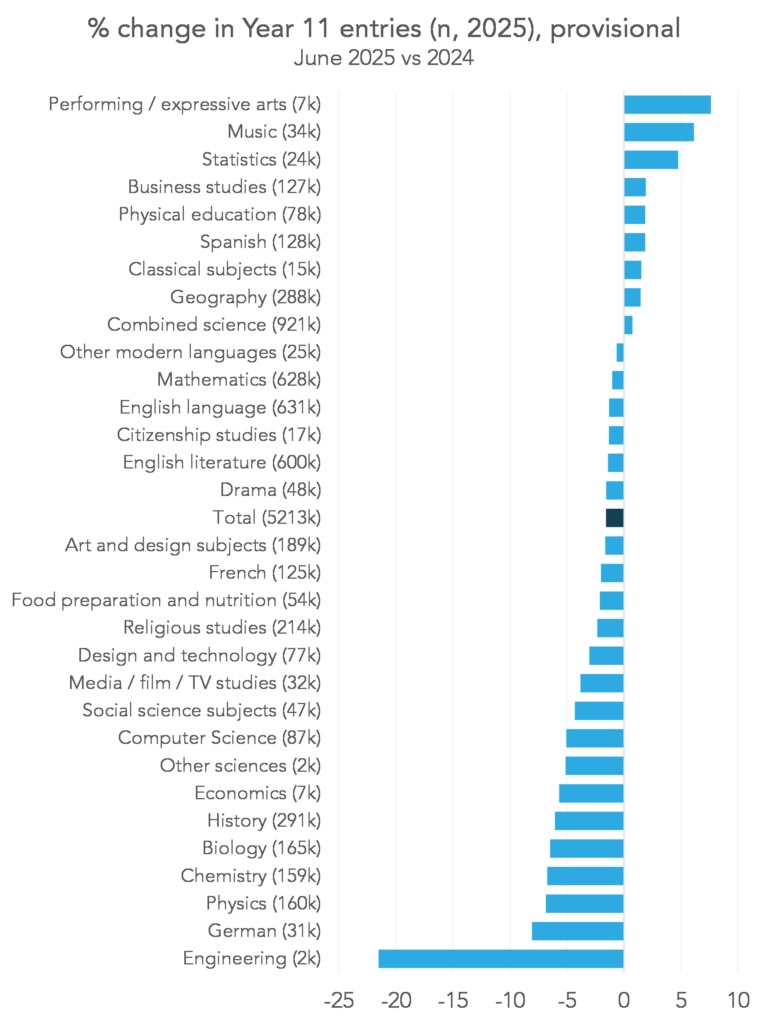

The total number of GCSE entries this year is down for the first time in a few years. We’d expected this to an extent, as we know that the population of 15-year-olds in state schools has fallen slightly. However, the fall in total entries is slightly larger in percentage terms than the fall in entries in English and maths, suggesting that the number of entries per pupil may also have decreased a little.

Building on increases last year, music, statistics, business studies, Spanish, geography and physical education have seen further rises in entries.

Spanish and geography aside, some of the EBacc subjects have not fared so well. Entries are down in German, biology, chemistry, physics, history and computer science.

Performing arts is the subject with the biggest percentage increase in entries, but, as it is taken by only a small number of students (6,855 this year vs 47,860 taking drama) it is prone to big swings year-on-year. Similarly, engineering, the subject with the biggest fall, has 2,280 provisional entries this year.

4. Shift from triple to double science

Another interesting thing in the provisional entries data is the increase in entries to double science accompanied by a decrease in the single sciences, biology, chemistry and physics. This is the second consecutive year where we’ve seen this happen[1]. Is this a two-year blip, or part of a wider pattern of schools shifting their offerings from triple to double science?

Depending on what happens with comparable outcomes, there may be an impact on the grading in these subjects too. With no Key Stage 2 data available, it won’t be possible to tell whether the “extra” students this year have nudged the ability of the double science cohort up or down.

If we assume they’ve nudged it up (which is likely because triple science pupils tend to be higher attaining than double), then might it be a little harder to get higher grades in double science this year? (Because, if boundaries are set to keep a similar grade distribution to last year, but the cohort is actually slightly more able, then there will be fewer top grades available for those whose work would warrant them.) Or perhaps the adjustments made by exam boards based on pupils’ work have successfully corrected for this, and we’ll see an increase in top grades in double science.

5. Re-take English and maths

While most of the focus of results day will be on Year 11 pupils, data on older students taking GCSEs will also be published. The vast majority of these are 16-19 students who did not achieve at least a grade 4 in English and/or maths at the end of Year 11, and are required to re-sit the qualifications until they do.

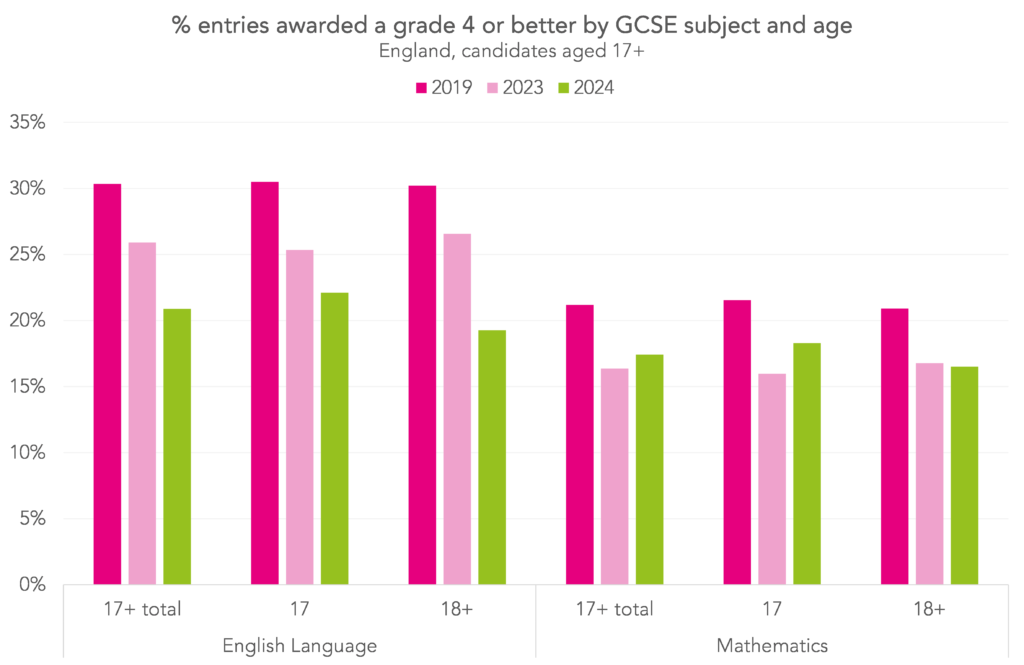

Last year was the first year post-pandemic where the re-sit cohort was broadly comparable to pre-pandemic re-sit cohorts, having made their first GCSE attempts in a year where pre-pandemic grading standards applied (i.e. in 2023 or later). So we expected to see grade distributions similar to pre-pandemic. However, this is very much not what we saw. The percentage of students achieving 9-4 fell, quite dramatically so in English.

16-19 providers have been asked to devote more curriculum time to these subjects, but it won’t become a requirement until the coming academic year. So, might we see an improvement driven by early adopters of this policy? Or will any potential improvements only come next year (if at all)?

Don’t miss our results day webinar, Thursday 21st August at 3pm. Sign up now for your free place.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

[1] Entries to the separate sciences last year didn’t decrease in absolute terms, but they increased by less than the size of the cohort, so decreased in relative terms. Entries to combined science increased by a greater amount than the increase in the size of the cohort.

Leave A Comment