Today the Social Market Foundation’s Commission on Inequality in Education publishes a new piece of work that we have co-authored, arguing that inequalities in access to high quality teachers across schools may contribute to social inequalities in educational outcomes.

Those who work in education often hear anecdotes suggesting that schools serving more disadvantaged communities have greater teacher recruitment difficulties. We wanted to see whether there was any systematic evidence for this phenomenon. We cannot observe the recruitment process directly, and so we use the School Workforce Census look for differences in the types of teachers who end up in different schools and at the length of time they stay.

We find higher FSM schools have more teachers without a formal teaching qualification or who are newly qualified, fewer experienced teachers, more teachers without a degree in the subject they are teaching (particularly in maths and science) and higher teacher turnover. These are all characteristics associated with classrooms where pupils make slower progress.

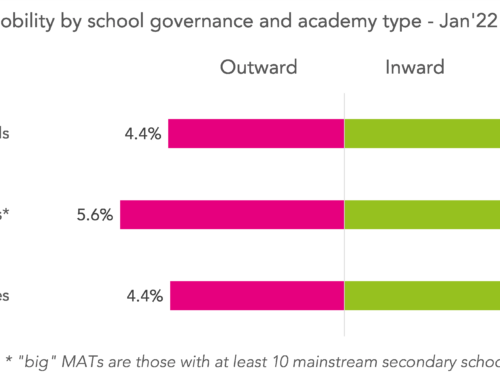

These differences are particularly stark for secondary schools, where the odds of a given teacher leaving a high FSM school are 1.7 times higher than for a nearby low FSM schools. Worse still, we suspect the rising recruitment and retention crisis will disproportionately affect high FSM schools.

Why don’t high FSM schools do more to attract and retain the best teachers?

In our report, we suggest two types of strategies for rectifying these inequalities in access to experienced and suitably qualified teachers. The redistribution strategy means finding ways to attract experienced teachers to high FSM schools, through pay or career incentives. The support strategy involves increasing the help new teachers in high FSM schools are given, thus aiming to retain them until they become more experienced and so breaking the cycle of inexperienced teacher replacing inexperienced teacher.

A couple of weeks ago Nick Clegg hosted a meeting of the Commission at the Sheffield Institute of Education and the headteachers and other participants who were there contributed to an interesting conversation about why high FSM schools do not currently use their funds to attract higher quality teachers. It was their view that there are inconsistencies in what is optimal in the short-term versus the long-term: since greater support for an NQT does not reap immediate benefits, instead money is spent on support staff, behaviour units and one-to-one tutoring that might be less necessary if their teaching staff were more experienced and stable.

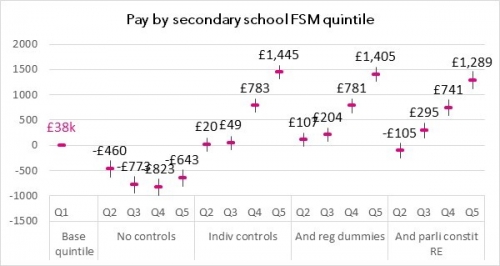

The most interesting piece of data, to me, was the observation that high FSM schools actually pay their typical teacher less than more affluent schools, despite having far higher per pupil funding. Even when teacher characteristics are taken into account, high FSM secondary schools only pay £1.3k more than low FSM schools located nearby. It would seem that this is nowhere near enough to attract large numbers of applicants to jobs at their schools.

Could pupil premium funds be used to attempt to reduce teacher turnover at high FSM schools? Higher pay might not be the best option here. The Sheffield headteachers gave examples of possible mentoring, support and career development programmes, including reduced teaching loads, to give new teachers at high FSM schools the best possible chance of succeeding in their career.

We know from other studies that young, newly qualified teachers often start their careers with a strong sense of social mission and so may often seek out positions in a more challenging school environment. We hope that our report will re-ignite the debate about how best to support these teachers who work with the communities that need them to thrive and survive in post.

Leave A Comment