Now that data from the National Pupil Database has been linked to earnings, employments and benefits records, we can begin to examine some really big questions about the long-term effects of education policy, structures and qualification choices.

Last, for example, the Institute for Fiscal Studies used this data to produce detailed analysis of the economic returns to higher education.

In this post, I’m going to look at whether pupils who attend a school with a sixth form achieved better long-term outcomes than pupils who went to schools without a sixth form.

Differing provision

We’ve looked before at geographic differences in how post-16 provision is organised [PDF]. In London, for example, students can access a large number of school sixth forms. Meanwhile, students in the north west are far more likely to go to sixth form colleges.

This variation arises from historic differences in the way areas responded to comprehensive reorganisation and the raising of the school leaving age in the early 1970s.

Should we expect the outcomes of pupils exposed to these different systems to differ?

Perhaps schools with sixth forms think more about progression, and offer qualifications at Key Stage 4 that are better preparation for study at post-16 and beyond?

On the other hand, research has shown that sixth form colleges have historically tended to be more effective than schools [PDF]. And, in the work mentioned above, we ourselves found that pupils who lived in areas without school sixth forms participated in post-16 education to the same extent as similar pupils in similar areas with school sixth forms, but made different qualification choices.

Comparing outcomes

In this analysis, we’ll look at three cohorts of young people – those in state-funded mainstream schools who turned 16 in 2003, 2006 and 2009.

This was a time when schools tended to receive a higher level of funding for post-16 students than colleges (see figure 4.1 of this [PDF]).

To start with, pupils are classified according to whether at age 16 they were attending schools without a sixth form, or schools with a sixth form. Of course, completing Key Stage 4 in a school with a sixth form does not necessarily mean you will progress to the sixth form. Most pupils who go on to study at Level 2 or lower – below A-/AS-Level – will do so in general further education colleges even if their school has a sixth form.

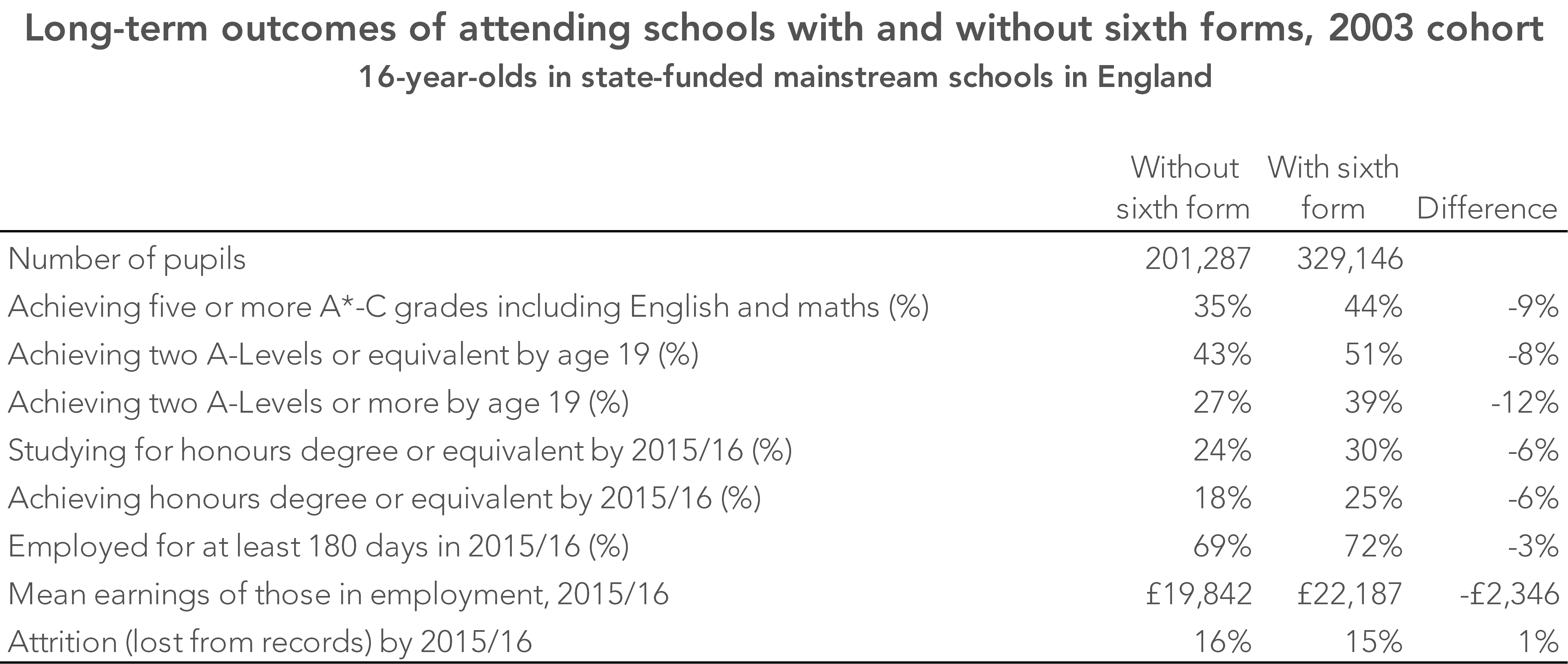

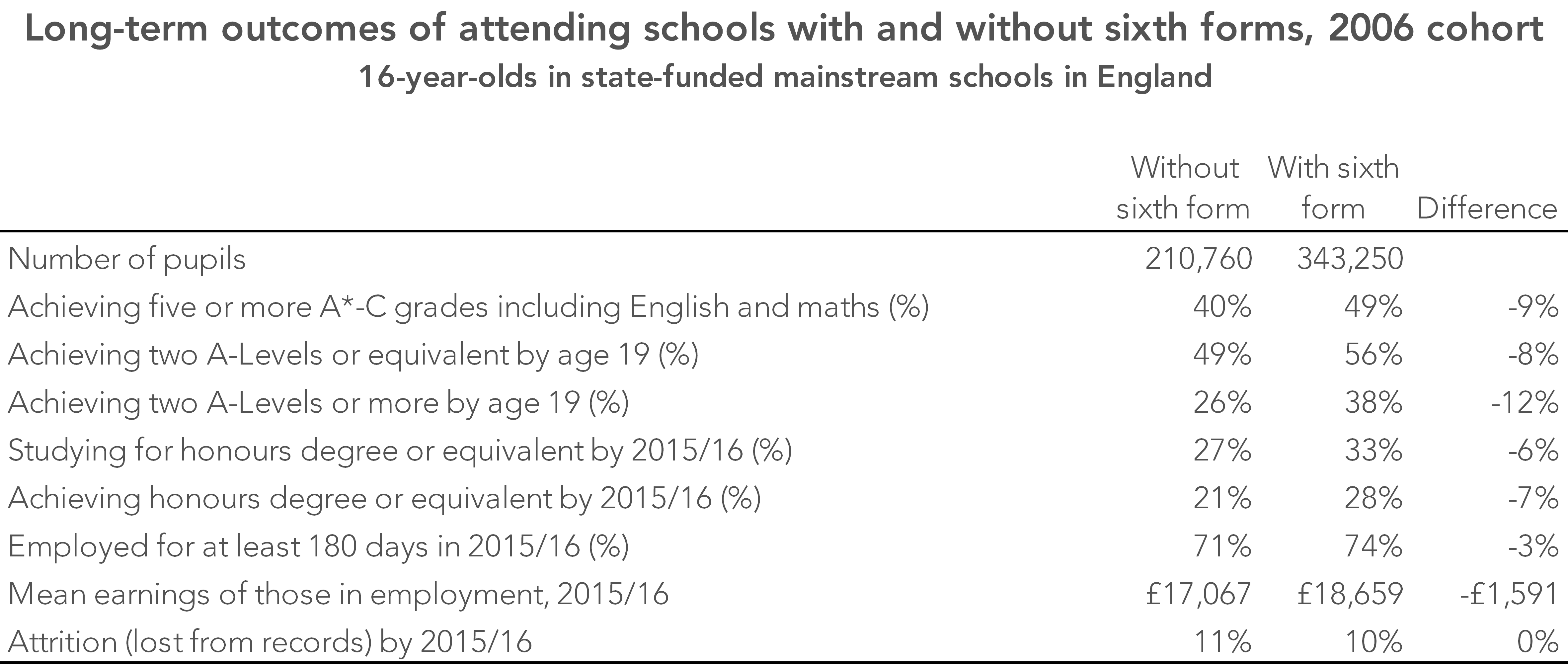

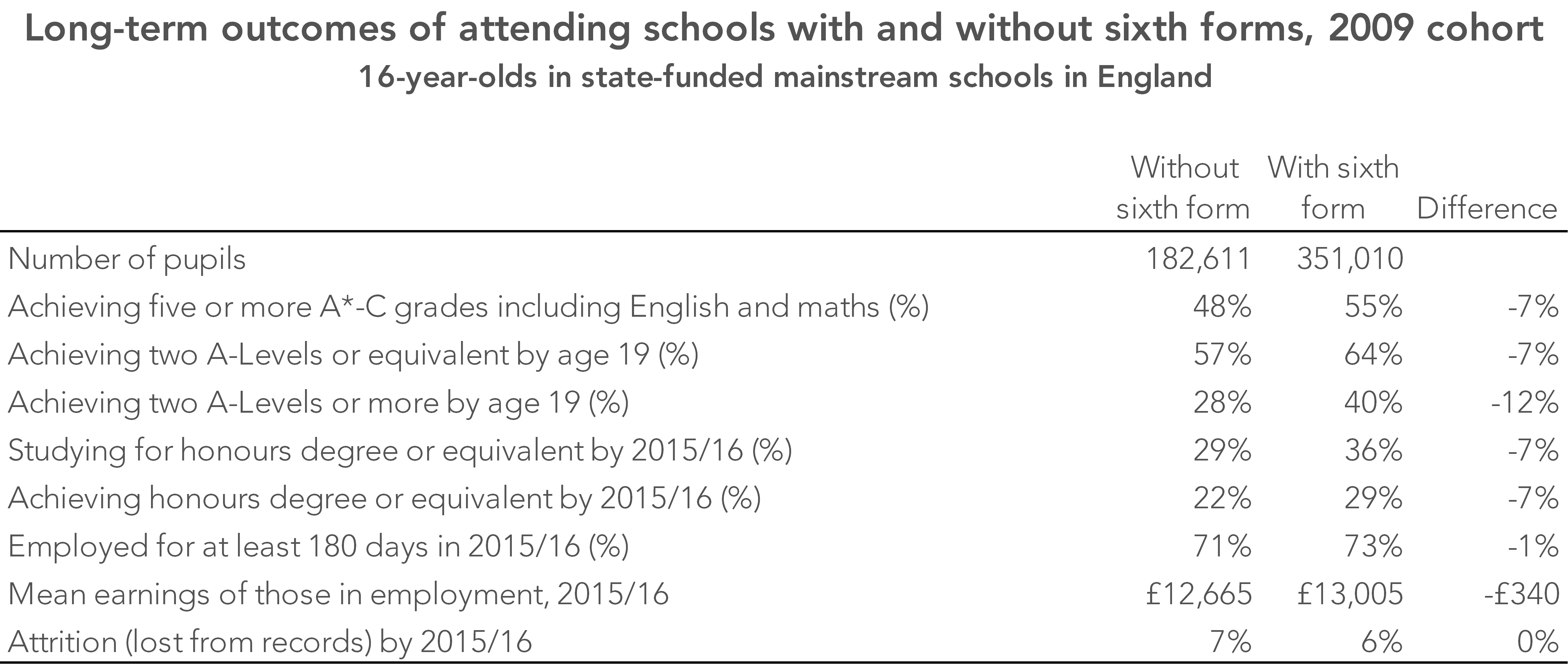

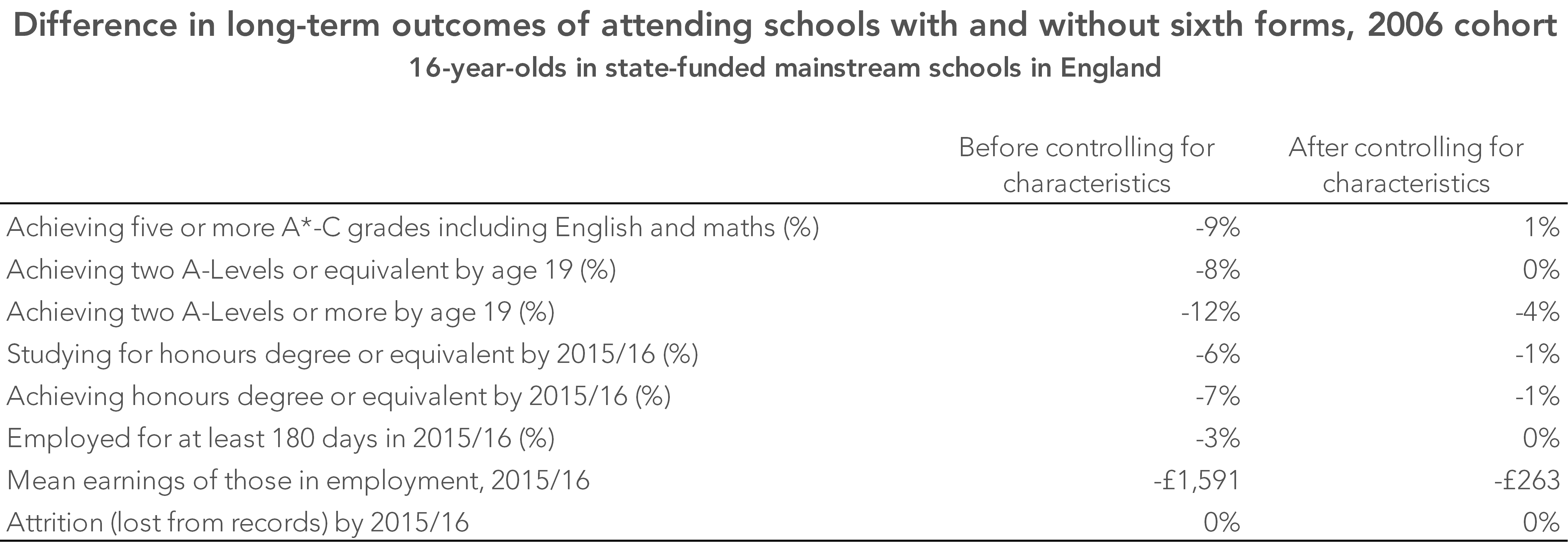

The tables below show a range of different outcomes for each cohort.

In general, pupils who attend schools with sixth forms tend to achieve better outcomes – having higher earnings a number of years later, for example. However, we are not comparing like with like. Pupils who attend schools with sixth forms are less likely to be disadvantaged, for example.

We can get round this by running a series of regression models on each of the outcomes in the table above, controlling for a range of pupil-level and school-level variables.[1]

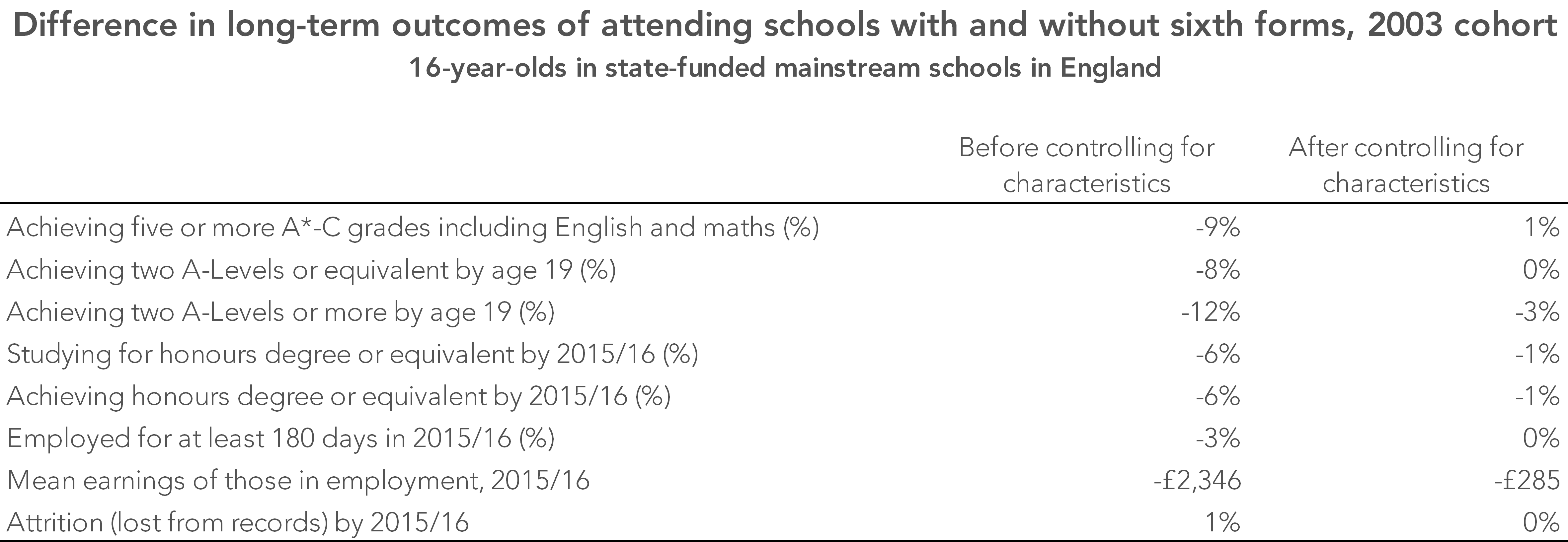

The tables below show the effect of this. It shows the differences before controlling for pupil and school characteristics, from the previous tables, as well as the differences once these factors are taken into account.

Controlling for differences in pupil and school characteristics virtually eliminates the raw differences in outcomes between pupils who attended schools with sixth forms and those who did not.

However, and in keeping with our previous work, pupils who attended schools without sixth forms were still less likely to achieve two A-Levels by age 19, although they were just as likely to achieve the equivalent of two A-Levels (formally, NQF Level 3).

This indicates that pupils from the two types of school tend to make slightly different qualification choices post-16.

Leading on from this, pupils who attended schools without sixth forms were slightly less likely to study for, or achieve, a first degree. Chances are we’d see differences in subjects studied and institutions attended too.

Now, I can’t pretend that any of this is causal. Although we can control for observable characteristics, we cannot rule out the possibility that any differences in long-term outcomes are the result of unobserved differences between the two groups. It’s not as if pupils have been randomly assigned to a school with a sixth form or one without. That said, it’s hard to see (for me at least) how a question like this would be tackled by anything other than non-experimental analysis of observational data.

So maybe there is a slight advantage to attending a school with a sixth form. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that there isn’t much difference, however. The quality and quantity of post-16 provision will be variable for both those who attended schools with sixth form and those who did not.

Furthermore, if schools did receive more 16-18 funding, then perhaps the slightly better outcomes associated with school sixth forms don’t represent better value for money.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Follow us on Twitter to get all of our research as it comes out.

The support of the Economic and Social Research Council is gratefully acknowledged.

1. The variables controlled for are: Key Stage 2 attainment, Key Stage 3 attainment, gender, free school meals eligibility at 16, ethnicity, English as an additional language, IDACI score of area of residence, special educational needs at age 16, term of birth, region, school mean KS2 attainment, school mean KS3 attainment.

The outcomes of pupils who attended schools without sixth forms can then be compared to the outcomes the models predict they would have achieved had they attended a school with a sixth form.

Leave A Comment