If you ran your school and didn’t have to worry about Ofsted and external agencies, how much data would you ask your teachers to collate?

Around 4-in-10 teachers think their school is collecting more data than they make use of, but 1-in-10 think they don’t have enough high-quality data to inform effective decision-making.

We know about these disparities in teacher opinion because earlier this year we asked thousands of teachers detailed questions about how data is currently being used in schools via the Teacher Tapp survey app. The survey forms the basis of a report we are publishing, How is data used in schools today?, that reveals many inconsistencies between current practice and what teachers feel would be useful.

How is data used in schools today?

To read more insights from our review of schools’ current practice around data use visit our dedicated site, where you can download a free copy of the report, ‘How is data used in schools today?’.

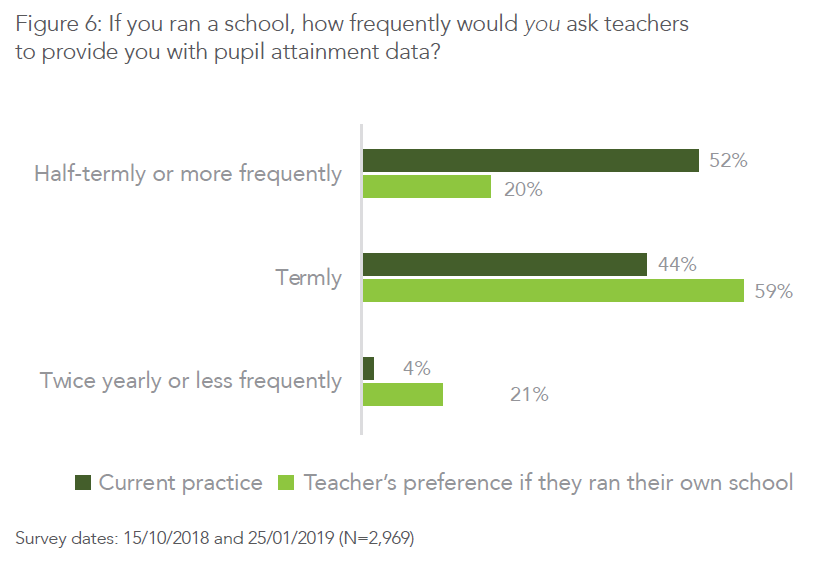

One example is the frequency of ‘data drops’ that take place in schools. When asked, half of teachers said they were asked to deposit pupil attainment data half-termly or more frequently and just 4% said they did it twice yearly or less frequently.

However, as the chart below shows, when asked their own preference just one-in-five would opt for half-termly data drops and a similar number would opt for very infrequent deposits.

Now, of course it is mostly classroom teachers who feel that data collection should be less frequent than is current practice. They are the ones for whom it takes up so much time, after all. However, we found that one-in-five headteachers believe their own data collection cycle is too frequent! Who is it that is forcing them to do something they believe is so inefficient?

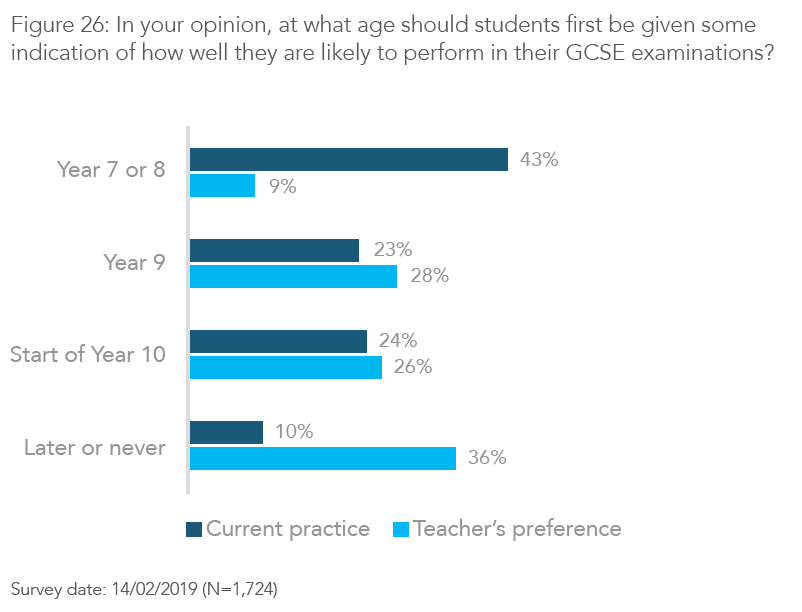

In secondary schools, one use of all this data is to generate target GCSE grades. In total, 4-in-10 secondary schools currently give indicative or target GCSE grades to students as early as Year 7 or 8.

As the chart below shows, very few teachers (just 9%) feel that this is a good idea and only 14% of those in senior leaderships teams would do this given a choice.

What is going on in senior leadership team meetings that means that current data practice is not reviewed and challenged?

I wonder whether those who aren’t responsible for data do not feel confident enough to explain why providing early predicted grades is unlikely to be helpful and could even be quite damaging to student morale.

The time it takes

For people who love data – myself included – the problem isn’t data per se, but the enormous time cost in collecting and inputting information that poorly represents student learning and attainment in a subject and gives teachers few steers as to how to adapt their practice. After all, if data has no role in adaptive teaching and learning, and it has an ambiguous role in motivating pupils or teachers, then it is hard to argue it is likely to improve school outcomes.

For example, primary teachers who rarely have externally-validated tests available in each subject are frequently asked to deposit at least 50 pieces of information about attainment. 50 pieces for 30 students means 1,500 data points! Let’s assume they spend just a minute flicking through a student’s work to decide what standard it is – then this still amounts to 25 hours a year, or at least a quarter of a primary teacher’s planning, preparation and assessment time.

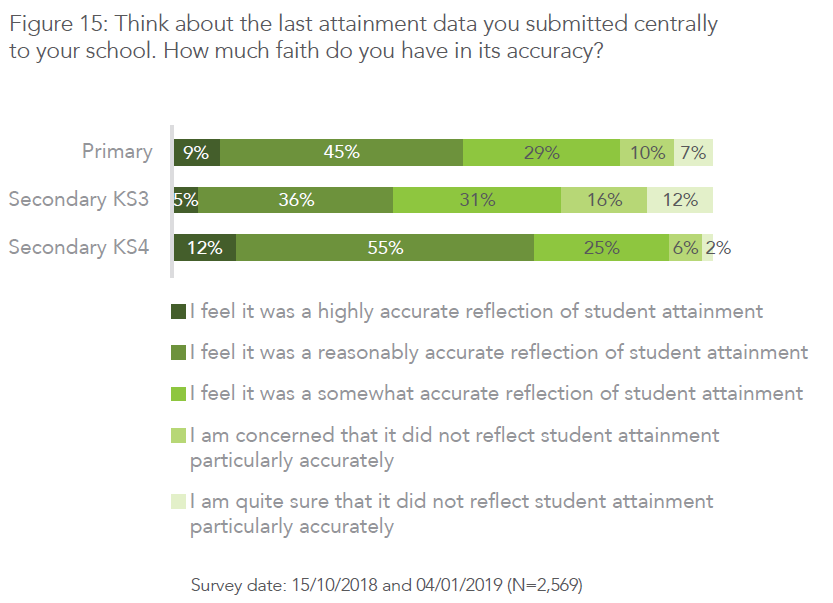

It is worth headteachers having an honest conversation with their staff about perceptions of data accuracy. If teachers don’t feel the information is accurate then there is little point in collecting it.

We know that maths teachers have the greatest degree of confidence in their attainment data, which is no surprise since measuring attainment in maths is relatively straightforward.

Our research also shows that teachers have little faith in interpreting data from a teacher-written test that is administered across just one class.

And overall, Key Stage 3 is the time when teachers are least certain that attainment information is accurate, as shown in the chart below.

Why might this be the case? Well, they see little of the students compared to primary teachers, so cannot form a holistic view of each pupil’s capabilities. And since there is relatively little commonality in curriculum across schools, they have little means to be confident that their own students are meeting the benchmark.

There are many more interesting findings from this research about schools’ use of data , so visit our dedicated site to learn more and to download a copy of the report.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

An interesting and relevant topic of research. I have no doubt that many schools and trusts collect a larger volume of data than is required for making well informed decisions. The focus however should not be about reducing the volume of data in and of itself, but in increasing the reliability of the data for the purposes, and audience, for which it is created. I do have a particular issue with research regarding data that itself adopts misleading infographics, for example the lead in at the top of the article (and contained in the report). I have therefore posted an infographic at the link below to illustrate a correctly scaled proportion (41% v 9%). I might also reflect on the same statistic suggesting that 59% believe that the right amount of data or not enough high quality data is collected. In all likelihood schools collect too high a volume of poor quality and unreliable data, which creates a workload issue and does not serve the variable needs of different audiences. What is needed therefore are intelligent approaches to reducing the associated workload in creating reliable high quality information that enables improved decision making for all stakeholders. There is good and emerging practice in this area, and further adoption of evidence based solutions need driving.

Hi Matt, thanks for the comment, and you’re right about the graphic. I’ve removed it from this post (though that does mean that anyone reading this comment won’t be able to see what it related to), and the PDF version of the report is going to be updated. I’m disappointed I missed this one.

Thanks Philip, it just jumped out at me as it was the first one… otherwise useful analysis, especially wrt addressing the value the shop floor derive from data v the executive. Those that want to see what my comment referred to can click on my name link, I hosted the comparison on imgur there… but I can remove that if you wish too!

Thanks, Matt – it was an entirely valid point. As you say, anyone who wanted to see the graphic as it originally stood can use the image that you’ve made available – that’s helpful.