The PISA 2018 results are out today.

PISA is supposed to test of a representative sample of 15-year-olds across more than 70 countries across the world. However, questions sometimes arise over how representative the PISA data really is.

And it seems that there were some problems with the PISA 2018 data for the UK. This blogpost will try to explain the issue.

The sample of schools

In PISA, schools are randomly selected to take part in each participating country. However, some of these schools refuse to participate. If the refusal rate is too high, then the PISA data may no longer be representative of the population.

Across the UK, around one-in-four schools (27%) refused to take part in PISA 2018. This is quite a high figure; the OECD typically sets an “acceptable” threshold of 15% or less.

Because of this low school response rate, the UK had to do a “non-response bias analysis”. In other words, the UK had to provide evidence to the OECD that the sample was indeed representative.[1]

The big problem with this, however, is that no details on the bias analysis have been published by the Department for Education or the OECD. The national and international PISA 2018 reports simply say that a bias analysis been done – and that things look okay – but without providing any detail.

This is odd, to say the least.

The sample of pupils

Even within participating schools, individual pupils can refuse to take part in PISA – or may be absent on the day of the test.

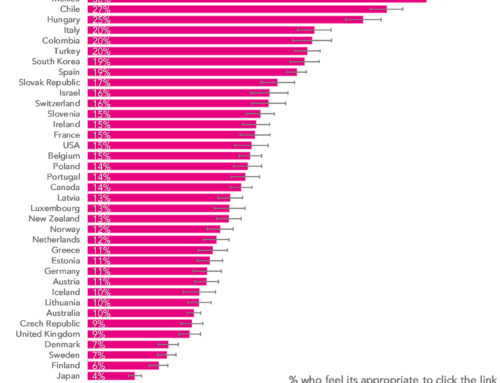

In PISA 2018, this also seems to have been a big problem in England. Around one-in-six (17%) 15-year-olds across the UK within sampled schools who were meant to take part in PISA were either absent or refused.

Indeed, there was only one country with a worse pupil response rate than England (Portugal).

This is not good, and again calls into question the quality of the data.

Testing “issues”

Finally, since 2006, PISA has been conducted in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in November and December. (Scotland always tested earlier in the year – around March to May – but also moved to November/December for PISA 2018).

However, it seems that the testing window had to be extended into January this time around.[2] This is highly unusual, and it is not clear how many schools this applied to.

The most worrying thing is what it says in the national report for England:

“A short time extension to the testing window was granted due to technical issues experienced by many schools. This was partly due to anomalies with the diagnostic assessment failing to detect issues with launching the [PISA test software].”

What were these technical issues? How many schools did it affect exactly? And what impact is it likely to have upon the PISA results for the UK?

Unfortunately, no further information has been provided. All we know is that there have been “technical issues” that affected “many schools”.

Implications

As I noted in a lecture that I gave on PISA last night, methodological challenges with PISA always arise. It is a crucial reason why we should not over interpret the results; particularly small differences across countries, and changes over time.

In fact, I think a swing of around 10 points in either direction for a country (as has been seen with England’s maths scores this year) should always be treated with great caution – and could well be due to methodological issues, rather than reflecting an actual substantive change in children’s learning and academic achievement.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. I have previously discussed this topic at length in a recent paper I wrote about the PISA data for Canada where there have been similar issues.

2. It’s unclear from the information available whether this was just the case in England, or whether it applies to other constituent countries of the UK as well.

“The big problem with this, however, is that no details on the bias analysis have been published by the Department for Education”

Can we push the DfE for an answer on this?

John is so right to point up sampling issues and schools/students not taking part. The English education system has seen schools (especially Academies and Free Schools) exploiting ever more varied and sophisticated ways of gaming GCSE results so no surprise that the issue has relevance to the issue of the reliability of English PISA scores and placings.

However, the other issue of varying cognitive ability in national PISA test cohorts remains a factor that no-one wants to talk about. See my article explaining my analysis of the 2015 maths maths scores

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2016/12/18/national-iqs-and-pisa-update/

The full analysis using the same methodology (endorsed by international academics) needs to be repeated, but the following 2018 data maths confirms the same pattern.

Places 1 – 7 are all East Asian countries. All of these have IQ scores of 106 (66th percentile) except Singapore with 109 (73rd percentile)

If these were student CATs scores in a English school they would correspond to students in Set 1/2 in a 4 set system

Now look at the rankings from 8th to the UK at 17th

8th – Estonia, 100 (50th percentile)

9th – Netherlands, 100 (50th percentile)

10th – Poland, 92 (30th percentile)

11th – Switzerland, 101 (53rd percentile)

12th – Canada, 100 (50th percentile)

13th – Slovenia, 98 (45th percentile)

14th – Denmark 99 (47th percentile)

15th – Belgium, 99 (47th percentile)

16th – Finland, 97 (42nd percentile)

17th – UK 100 (50th percentile)

The following conclusions follow

There is nothing exceptionally effective in the East Asian education systems

The star systems are Estonia, Poland, Slovenia & Finland (again)

The UK is performing relatively poorly, which alongside the negative conclusions about student well-being and stress levels is a worry.

Maths is the subject where the UK comes out best.

Despite a large number of visits to my website following my last reply still no comments or refutations to my argument.

I assume this is down to discomfort with my use of the term ‘intelligence’ on account of associations with eugenics.

What is truly astonishing is that the concept of intelligence is so universally accepted in all contexts except education, where it is obviously of most relevance. Here is an extract from a Sunday Times article of March 2017.

People exposed to high levels of leaded petrol as children are still suffering from lower intelligence 30 years later, according to the largest study of its kind. Since the 1970s, lead in petrol has been phased out across the world amid concerns that it affected health. It was not until 1999 that it was finally removed from petrol pumps in the UK. While scientists in the US have estimated that removing the additive has raised average IQ by almost five points, establishing the link between cognitive decline and lead has been difficult, in part because those most exposed to lead are often in lower socioeconomic groups.

See my article

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2019/08/19/intelligence-mustnt-be-ignored-by-educationalists/