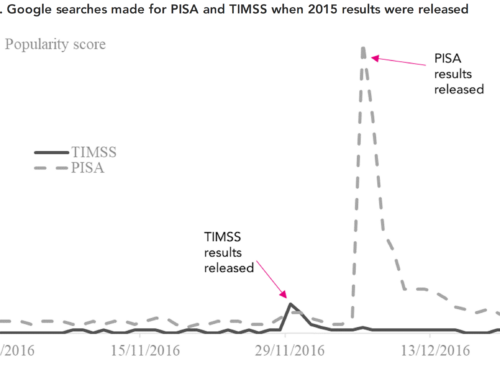

On Tuesday 5th December, the latest results from the OECD’s PISA study will be released. For those who don’t know, PISA is an international test of 15-year-olds across the world, with the results widely used to compare educational standards across countries and over time.

Here are some things I will be looking out for when the results get released – along with some other nerdy details that I think its worth keeping in mind.

1. Will COVID shake up England’s PISA scores?

There have been some positive signs recently in England’s PISA scores. There is some evidence of an upward trend in reading performance over time, increasing by 10 points between 2006 and 2018. Maths scores also ticked up by 11 points in 2018, though after a long period at the same level.

But, if anything is REALLY going to really shake PISA scores, its COVID.

My prediction is that we will see PISA maths scores in England fall back. This is partly based on what we have seen in NRT mathematics scores since COVID which – like PISA – tests Year 11 students. But its also because England’s 11 point uptick in maths scores in 2018 maths wasn’t part of a longer-term trend, which always makes me a bit nervous it could have been partly driven by statistical noise.

For reading, I also think our scores will fall back a bit, but not by as much in maths. This is again driven by observations from the NRT, but also more generally the evidence surrounding COVID learning loss (where English seems to be a bit less impacted than maths).

2. It is important to remember the UK tests later than other countries

PISA does not test all students across the world on the same day.

In most Northern Hemisphere countries, teenagers take the PISA test sometime around May. But the UK conducts the tests around 6 months later, in November/December.

Why does this matter?

Well, this time around it means teenagers in our PISA sample will have had around six months more time to recover from COVID learning loss than those other countries. In terms of cross-national comparisons, the PISA 2022 dice may to some extent be loaded in our favour.

So – although I think our PISA scores will fall back (particularly in maths) – they may well hold up better than in some other countries. If they do, then these six precious months could well form part of the explanation.

3. Will the limitations with the data be more transparently reported this time around?

I have heard various rumblings over the past year that the PISA 2022 data for the UK might have some issues. Exactly what, I am not sure. But issues surrounding participation rates have been a long-standing issue.

When the PISA 2018 results were released back in December 2019, the OECD and the four UK governments tried to hide some important details away, as I discussed in this series of blogs. They have made promises to do better this time around.

If there are similar issues with the PISA 2022 data – which the rumours I have heard suggest – then lets hope the OECD and UK governments are a bit more transparent about the caveats that need to be applied.

4. Keep an eye on the pupil absence rate

Why is the point above important?

Well, due to COVID, one of the things many countries are dealing with is higher school absence rates. And, if kids ain’t in school, they can’t sit the PISA test!

If greater numbers of academically weaker 15-year-olds are missing school now than previously, then this could bias the PISA score (likely inflating them upwards).

This may impact both comparisons over time (to the extent that there is more absence now post-COVID than previously) and across countries (to the extent that absence rates have increased more in some than others).

In countries where PISA scores hold up better than expected, then we need to think about whether this may be one of the reasons.

Leave A Comment