Once upon a time – when Michal Gove was Secretary of State for education – PISA was all the rage. As I noted at the time international evidence was then en vogue, with PISA in particular featuring prominently in education debates.

But is PISA now receiving less attention than it used to? In a new academic paper published today I take a look…

Google Trends data

To investigate whether PISA is now receiving less attention than previously, I draw on data from Google Trends. In a nutshell, this provides information on the number of searches made for a given topic (e.g. PISA) in a given geography (e.g. England) over a given time horizon.

A monthly or daily score between 0 (very few Google searches) and 100 (most Google searches over the given time period) is then returned. A value of 50 on this scale would then indicate that half as many searches were made for the topic relative to its peak.

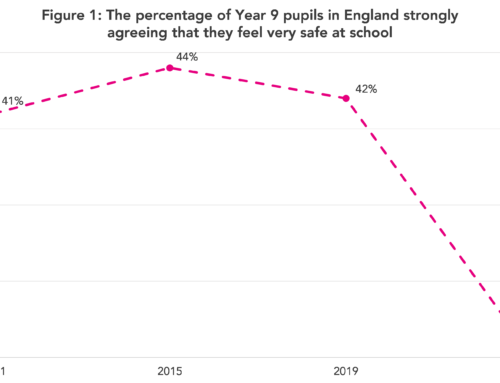

Figure 1 presents the trend for Google searches made for PISA across the UK between 2006 and 2022. Once can instantly see three or four large spikes in the trend. These coincide with when the results from PISA were released. “Peak PISA” in the UK was December 2013 – when Michael Gove was in office and pushing through his reforms and the results from the 2012 round were released.

However, with every subsequent release, the attention the PISA results have received in England has been lower and lower. For instance, when the PISA 2018 results were released in December 2019, the number of Google searches for the results (relative to all Google searches made) was at only about 40% of the level of its 2012 peak.

How much attention does PISA receive compared to TIMSS

PISA is not, however, the only game in town. There are other international assessments – such as the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) – that are equally (or arguably more) robust resources facilitating the comparison of educational achievement across countries.

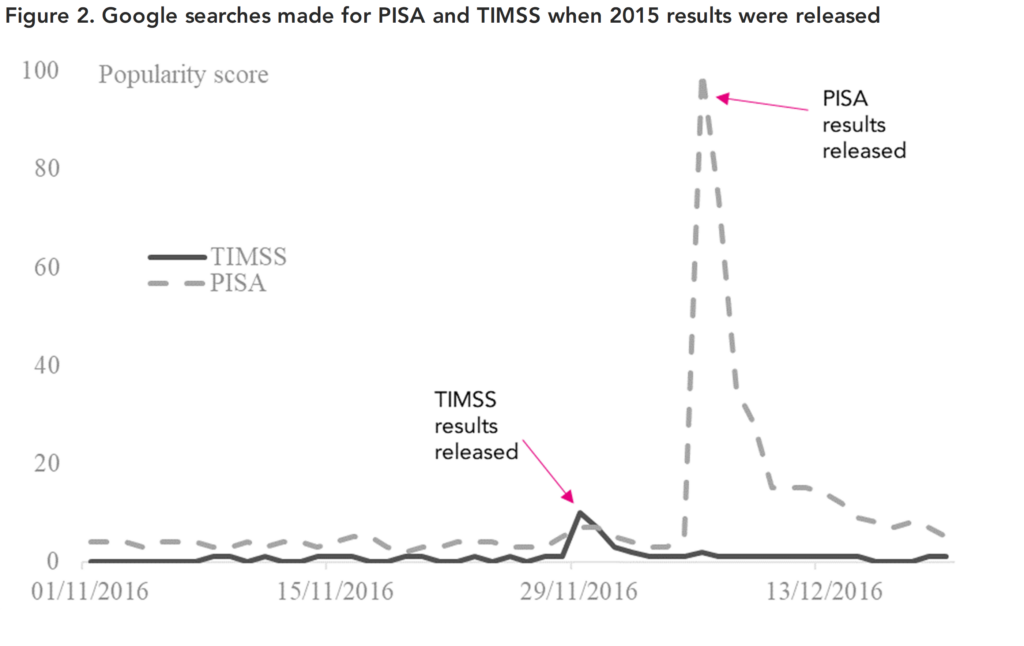

In my new paper I also investigate the amount of attention that various different international assessments receive. Figure 2 – based upon Google searches made across all countries – presents a comparison of PISA and TIMSS. It focuses on the release of the results from the 2015 cycle from both studies, which occurred just one week apart.

As Figure 2 illustrates, the PISA results receive much more attention than those from TIMSS. In particular, even though results from these international assessments were released just one week apart, PISA received around 10 times more Google searches globally than TIMSS.

Indeed, In the UK, the difference between PISA and TIMSS was even starker – with 20 times more searches for the former than the latter. In fact, in the UK, the release of the TIMSS 2015 results actually led to more interest (Google searches) for PISA than for TIMSS!

Why does this matter?

In much of my previous work, I have advocated one should take a holistic approach to international evidence. PISA, TIMSS and other international (and national) data all provide complementary evidence that can help us to understand how educational achievement (and education systems) compare across countries.

In this respect, PISA’s dominant position – in terms of the disproportionate amount of attention it receives – is unlikely to be helpful. It is, after all, not who shouts the loudest that matters most, but rather who has the most constructive insights to offer.

Leave A Comment