It nigh on three years since we first published Who’s Left, our work that provided the first proper account of how many pupils were leaving mainstream school rolls, where they were going – and, in many cases, why outcomes looked so poor for them.

Bar Ofsted picking up the mantle and starting to look at off-rolling, little of real substance has changed in terms of education policy.

And the number of pupils leaving mainstream school rolls are continuing on an upward trend.

Leaving the system

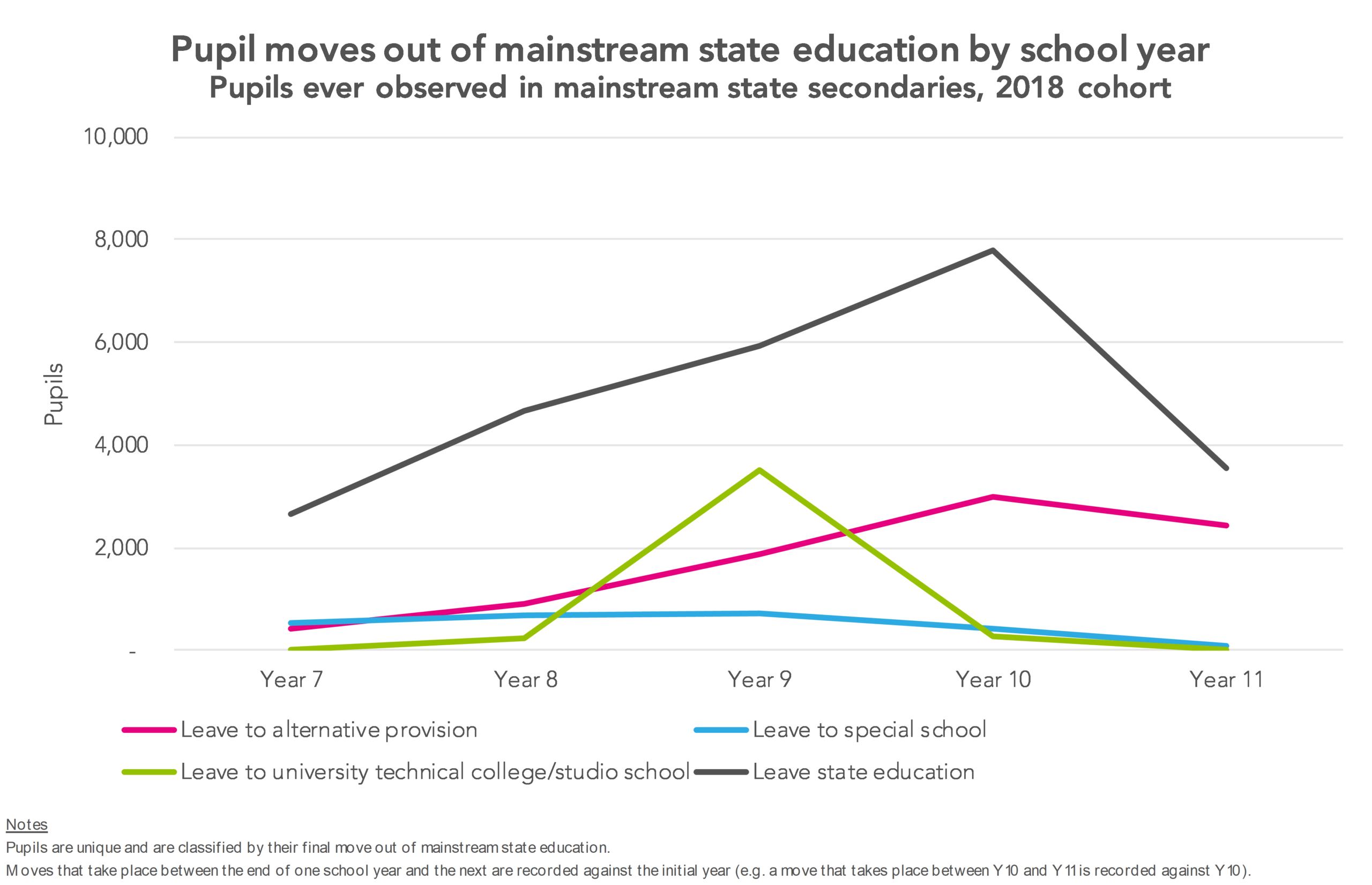

In the summer of 2018, 549,000 pupils who had spent at least one term at a mainstream secondary school reached the end of Key Stage 4. Just less than 39,800 of these pupils left mainstream education at some point between Year 7 and Year 11.

Around 8,600 left to state alternative provision. Another 2,500 moved to a state special school. And around 4,100 moved to a university technical college (UTC) or studio school.

The largest group, of 24,600 pupils, left state education altogether, however.

The chart below shows how these groups compare in size, and the point at which they left mainstream education.

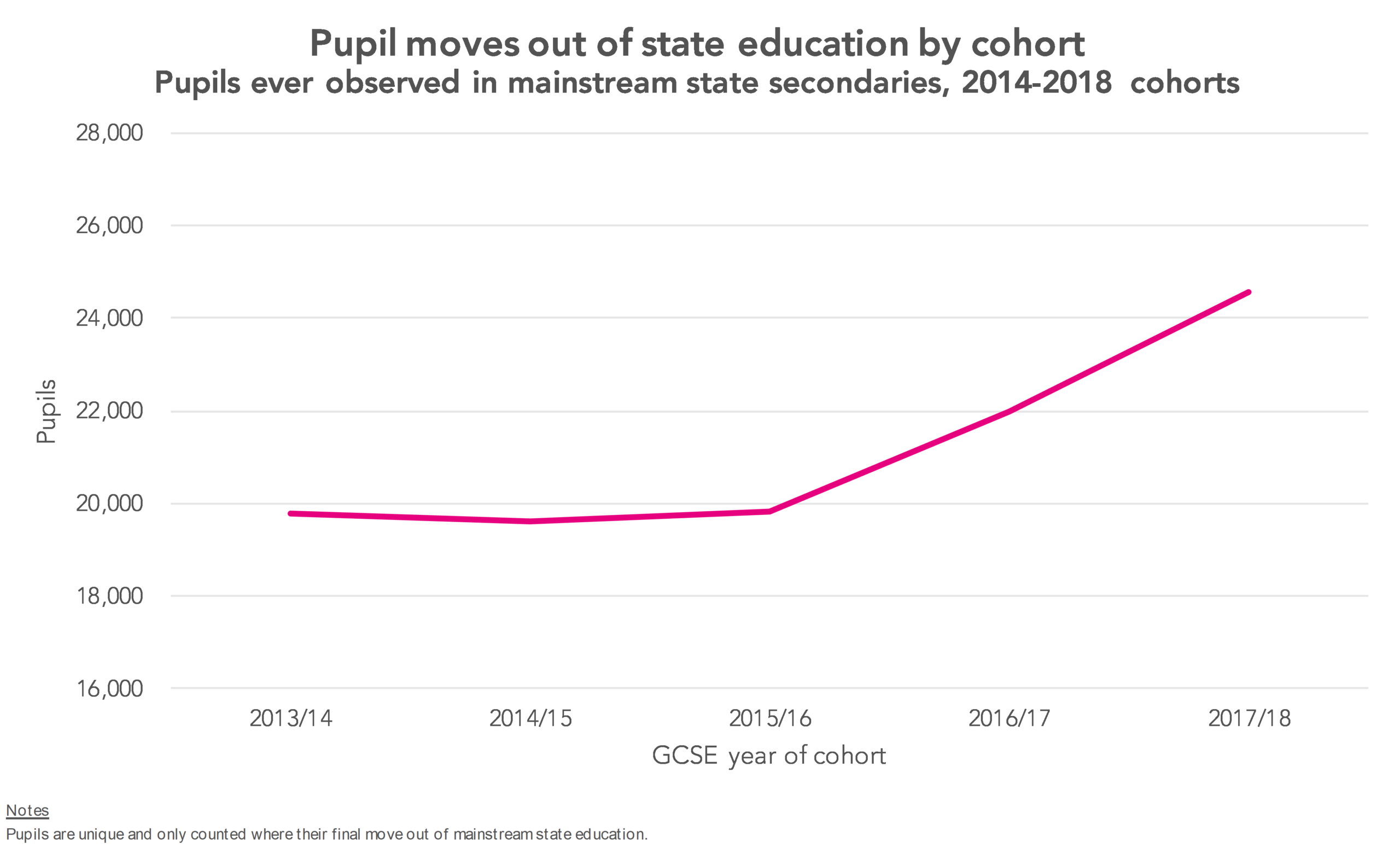

The size of this group who left state education concerns us, as does the fact that it is an increase on the 22,000 pupils who left state education from the previous year’s cohort, and well up on the years before that, as the chart below shows.

At this point it’s worth pausing to state a number of things.

1. Not all of those leaving state education are of concern

The group seen leaving state education will be going to one of a number of destinations, and for a number of reasons.[1]

Some pupils will enter independent mainstream schools or independent special schools, either as a result of entirely free parental choice or to ensure that a child’s needs are best met.

Others will have left to independent alternative provision. While we’ve noted previously that inspection ratings for this part of the AP sector appear below those for state AP, that in itself doesn’t place the group of pupils who leave to this destination as of most concern in our minds.

Some will have left England – a point we’ll return to.

And others will have entered home education.

The rising estimates of the number of pupils in home education suggest that this is indeed somewhere where children who leave mainstream school roles are likely to end up.

Parents are perfectly entitled to do this, of course. We would only be concerned if they ended up doing so when they would have preferred otherwise.

Some of these pupils may be attending unregistered alternative provision, about which we know phenomenally little; some others will be experiencing an education in name only.

2. Not all of those leaving to other parts of the state system are not of concern

It’s worth stating briefly that we are not equating staying in the state system with positive outcomes for a child. Many of those in state education – and some groups, such as disadvantage pupils more than others – will not have positive outcomes, as we’ve documented many times before.

3. Leaving the state system can’t be treated as synonymous with off-rolling

Without knowing individual children’s circumstances, leaving state education can’t be treated as synonymous with off-rolling, even in cases where we go on to see the pupils not sit any qualifications.

You also don’t have to leave the state system to be off-rolled. It can involve a move to a different mainstream school, to alternative provision or to a UTC or studio school.

No excuses

Returning to this group of 24,600 pupils from the 2018 cohort who we saw leaving the state system, to understand more we need to drill down further.

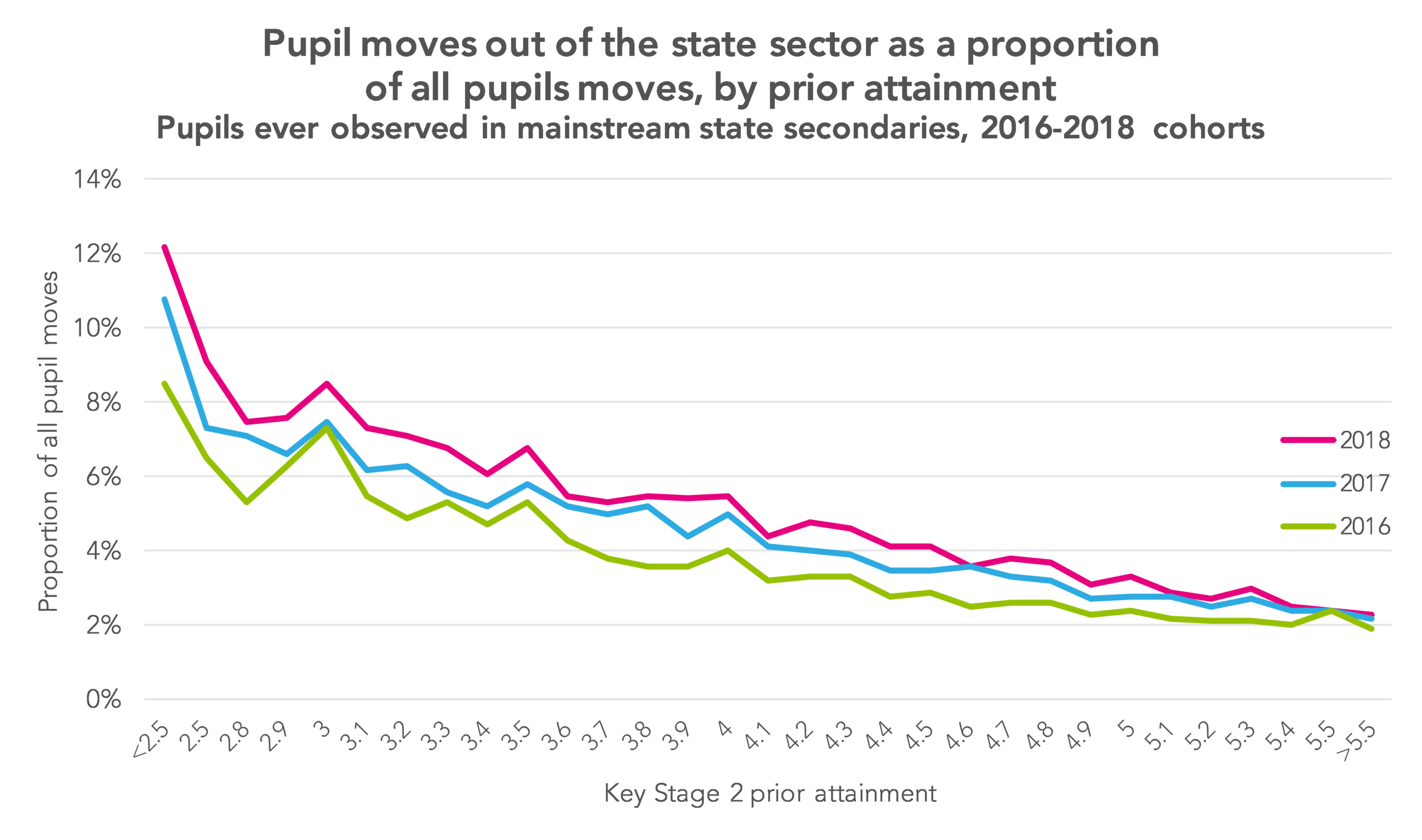

As a percentage of all observed pupil moves, those towards the bottom of the attainment scale are more likely to make moves out of the state system.

And as the chart below shows, a greater proportion of pupil moves for the 2018 cohort were to destinations outside of the state system than was the case for the previous two cohorts – this is true across the ability range, though it seems to be particularly the case for those towards the lower end of the prior attainment scale.

A total of 16,700 out of our group of 24,600 pupils seen leaving state education either took no qualifications, or, if they did, did not count in the results of any establishment. A little over 5,800 of these pupils were disadvantaged.

Some of these pupils won’t be counting for quite clear reasons. It’s hard to be precise about the number of young people who emigrate or move to other parts of the UK, but once these factors, plus mortality, are taken into account we estimate that 6,700-9,200 pupils remained in England and yet did not take any qualifications or, if they did, did not count in results anywhere. That compares to our estimate of 6,200-7,700 when we looked at the previous cohort last year.

Something is wrong when this can be the case.

Now read our recommendations for things that the government needs to do to tackle this issue.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. Being strict with definitions, some will be attending further education as a form of alternative provision, which is within the state system but outside of the datasets used in this work. Other data that we’ve used suggests this accounts for a relatively small number of pupils.

Leave A Comment