Updated 14th August at 10.40 to make an important clarification about adjustments for prior attainment not taking into account historic value added at centre level.

Schools up and down the country are trying to get their heads around the process that Ofqual, the exams regulator, has applied to calculate A-Level grades.

The process is described in some (but not full) detail in the 319 page Ofqual technical report and further detail can be gleaned from an accompanying data specification.

Awarding bodies have provided schools with standardisation reports, supposedly to show how they have arrived at the calculated grades. But these leave more questions than they answer in my view.

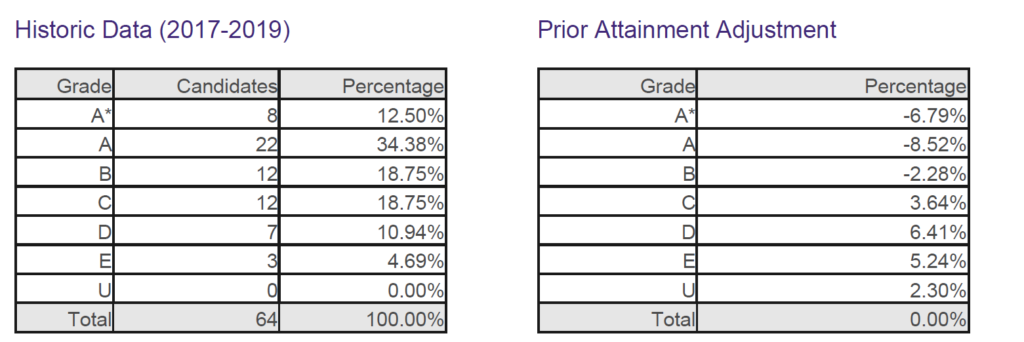

Here’s an example from a school that has kindly shared a section of its report with us. To protect confidentiality the school and subject is unidentified.

In this subject, the left-hand table shows that 12.5% of entrants achieved A* between 2017 and 2019. And none achieved a grade U.

Now let’s turn to the right-hand table. If the prior attainment for the 2020 cohort matched the 2017-2019 cohort (on average), there would be no adjustments and the historic grade distribution would be used to award 2020 grades.

But for this school, the top grades are lowered. Based on the prior attainment of 2020 pupils and the historic relationship between prior attainment and A-Level results in this subject nationally and adjustments to achieve the desired national distribution of grades [1], the historic A* rate should be lowered by 6.79 percentage points. Or put another way, the calculated 2020 A* rate at the school is 12.50% – 6.79% = 5.71%. And although no one achieved U between 2015 and 2017, the model predicts that 2.30% should this year.

This immediately suggests that the prior attainment of the 2020 cohort was lower, on average, than that of the set of pupils from 2017 to 2019. However, there does not seem to be any way for schools to check this.

The prior attainment adjustment also does not appear to take account of historic value added at the school. So in schools with historically high value added, the prior attainment adjustment will result in grades being lowered.

Using the two tables above, we can calculate the 2020 expected grade distribution for this school in this subject.

Using column D, the allocation process begins. 27 pupils took the subject in 2020. Each pupil counts as 3.70%, as two A* grades (7.4%) would exceed the expected A* rate (5.71%). Consequently, just a single A* grade is awarded.

The full mix of grades awarded can be seen in the table below.

Unfortunately, one pupil is awarded a U. This seems rather harsh given that the model prediction is for fewer than one pupil (2.30%, when each pupil counts as 3.70%) to achieve this grade.

The table above headed “prior attainment adjustment” is absolutely fundamental to understanding how this year’s grades have been calculated. Unfortunately, it raises more questions than it answers.

It would be helpful if two tables were produced, one showing the prior attainment adjustment, the second showing any further adjustments (up and down) as a result of Ofqual trying to achieve the desired national distribution of grades.

(Tom Haines has produced a great visualisation of the first part of the prior attainment adjustment- follow this link).

The technical documentation suggests that Ofqual uses an age-standardised version of GCSE average point score. This is a good idea as GCSEs have been reformed in recent years. Those entered in 2015 by 18 year olds who took A-Levels in 2017 were all graded A*-G. Those entered in 2018 by 18 year olds who took A-Levels in 2020 will mostly have been 9-1, with some A*-G grades.[2] Although there are point score conversions that are used conventionally, they are not strictly equivalent.

In order for schools to do detailed checking it would be helpful for them to be given the measures of prior attainment used and how they have been banded in each subject, both for 2020 pupils and for historic pupils. In addition, the national prediction matrices and details of adjustments made to pupils close to grade boundaries would be necessary.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. Ofqual runs some further analysis to identify pupils notionally close to grade boundaries to move some up a grade.

2. Anyone who tries to calculate value added using the 2019 Department for Education value added calculations is likely to find that it has fallen in 2020. This is because GCSE average point scores increased in 2019 as a result of more GCSEs being graded 9-1. Consequently, expected grades will be too high.

Is this really how it works? I thought there was a step in between this naive allocation and actual calculated grades using “imputed marks” and a national standardisation to set “imputed grade boundaries”?

I just am finding it hard to believe they are rounding down (never exceeding) and not picking the closest approximation to their predicted grade distribution given the discrete nature of the distribution

Hi Richard. Yes, I mention the additional step after the final table but not in much detail as I can’t be clear how it has been applied. But I think it contributes to the “prior adjustment” table. Again, more info should be provided.

Thanks this is helpful. Can you say how prior attainment is calculated for GCSEs particularly schools in the independent sector who may not have Key stage 2 data to draw upon?

Hi John. Thank you. In short, it isn’t. As far as I can see, the model assumes that pupils without prior attainment at a school will achieve similar GCSE results to pupils without prior attainment at the school in the past.

Hi Dave,

The KS2 prior performance data for this year’s GCSE cohort will come from 2015. That year only 338 out of 1400 Independent schools took part in SATS. Surely that means over 1000 schools not having grades subject to the Prior Performance adjustment? That is quite a large number, given the negative effect the PP adjustment had on the school you exampled.

The model uses national value added data and ignores the centre’s historical record. Centre’s with a record of consistently high value added will have been given a set of low grades belonging to other centres. At student level these will have been shared out across the classes.

Value added for most able students is limited by the grade ceiling. It is those with more modest KS4 scores where value added (of the removal of it) is most clear. For centres with high prior attainment this problem is not obvious, for those with a high number of small groups it will only show at granular level. For high VA centres with a comprehensive intake and larger groups these results are likely to the be the worst in years. These centres often serve deprived communities so this has been described as a post-code lottery. I don’t think it is post-code.

Hi Steve. Thank you. What makes you think the centre’s historical record has been ignored? The technical documentation suggests it has (though we’re still trying to work out just how).

Hi Dave

p & q (and p-q as the correction factor) all use national VA.

Steve

Thanks Steve. Looking at it with fresh eyes, I think you’re right. This is worse than I thought. There’s no such thing as “national value added” which is why I assumed it applied at school level. Will spend a bit more time redigesting it. Thanks again!

But does this matter, if the additional value add of the centre is added to both p and q, they would cancel.

I agree, Steve. p is historical national VA, q is the national VA prediction for summer 2020. This is stated in the data specification steps X6 to X8. Historical national VA is calculated in X3 from awarding body datasets without reference to centres, and then applied to centres in X4. Step X5 generates the predicted outcome for each centre for summer 2020 “were they to follow the national value-added relationship defined by the historical oucome matrix calculated in X3”. Centre-level VA is never subsequently fed into the calculation. Thus the eventual predicted grades take no account of centre-level VA. This appears to be an intentional feature of the model.

Yes that’s right. They say so in the final para of section 8.2.3 of the technical manual. I couldn’t believe it at first when Steve pointed out but it is absolutely clear. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/909368/6656-1_Awarding_GCSE__AS__A_level__advanced_extension_awards_and_extended_project_qualifications_in_summer_2020_-_interim_report.pdf

It would be useful if you could comment on this:

https://twitter.com/a_weatherall/status/1294012623776817158?s=21

Hi Ben. Both the blogpost and Alex’s tweet stem from a conversation we had last night.

If you are both right, doesn’t this mean that the lowest ranking student must always receive the lowest grade with a non-zero expected percentage (because otherwise there would always be a little bit of that lowest grade left over that has to be attributed to some unfortunate individual)?

Is the percentage expected at U ever exactly zero (is there some specified precision for this)?

To clarify – my thread has an error in it. Non zero % is quite right. The assignment rounds to the nearest whole student. This still leads to grades bubbling down – in some cases to a U. But not simply because the % is non zero. It would have to be greater than 0.5*(100%/cohortsize). So in my example I should have set it to 2.5% (1/2 of 5%).

Just for the record. Following Alex’s Twitter clarification it seems that this won’t happen.

In order for schools to do detailed checking it would be helpful for them to be given the measures of prior attainment used and how they have been banded in each subject, both for 2020 pupils and for historic pupils. In addition, the national prediction matrices, the school-level value added adjustments for each subject and details of adjustments made to pupils close to grade boundaries would be necessary. Will schools be able to access this in order to support the appeals process?

Hi Sonia. Not sure for certain but from conversations with a few school data managers it hasn’t been made available. I don’t know if the boards have plans to make it available.

Is this the methodology for 15+ entries only? What happened for the 6-14 cohorts where some account was taken of CAGs? I realise that <=5 cohorts has their CAGs ‘waived through’.

Also, wasn’t it a significant flaw to not limit grade changes to only 1 up or down. A ‘B to U’ scenario is not just.

Hi Jo. Thank you. Yes, for 15+ entries. I should make that clear. As for moving from B to U, yes, this does seem excessive. I suppose it could be argued that CAGs were beyond optimistic in exceptional cases which meant it was done.

Thanks Dave. I suspect that poor student was at the bottom rank of a very able group and the rounding up algorithm insisted that a U grade was required. You can get the odd U of course, but from a student predicted B???

Why didn’t they limit how far a grade could drop?

It would be helpful if appeals consider the subject’s track record at that school from a L3VA perspective. It’s all very ‘checkable’.

Agree. In fact, I don’t think the school’s L3VA record has been taken into account after all when making the prior attainment adjustment (see comments with Steve McArdle). So I think this is where U grades are creeping in.

The most pernicious aspect of this is the lie that Centre Assessed Grades and therefore the professional opinion of tens of thousands of teachers were used in the process at all. The fact that the outputs generally correlate is an upshot of the process rather than a use of that data

Hi Michael. I expect Ofqual would say that the rankings provided by teachers were fundamental to the process. In the technical manual they draw a distinction between “absolute accuracy” and “technical accuracy” (Section 3.1 of https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/909368/6656-1_Awarding_GCSE__AS__A_level__advanced_extension_awards_and_extended_project_qualifications_in_summer_2020_-_interim_report.pdf)

Perhaps only ranks should have been asked for. It would have helped. For some teachers, it gave false expectations.

HI,

I am sure they would but they asked for two pieces of information, I suspect to lend the process legitimacy, and then ignored the CAG. It is still being pushed by the media that they used the CAG and ajusted it rather than the true picture.

Also something that remains unchallenged so far is the notion that we predict A level results and that those predictions are wildly inaccurate, 16% achieving their predicted grade is the figure being touted around at the moment.

It is a good 5 or 6 years since Exam Boards asked for predicted grades for A level entry. I assume the analysis is of UCAS predictions which are over-egged so that students can get a foot in the door of better institutions. Also, they are made at least 10 months before the exam season begins.

The stack ranking of students prior to the automated algorithm just provided a pseudo-anonymised profiling for the generated grades to be attached to. Qualitative judgement was absent from the process the moment CAGs were dropped. It would have been preferable for the algorithm to come up with the grades for each setting and then let teachers allocate and moderate where necessary for their local cohort.

In the model above then, where the lowest grade grade has more than 0 but less than 1 student then the lowest ranked student gets a ‘U’. Surely given OFSTED’s commitment that ‘In developing the model we have sought, where possible, to make decisions that work in students’ favour when awarding grades this summer.’ then grade distribution should always round up – So more than 1 and less than 2 students modeled A* – Top 2 get etc… Cumulatively down the distribution. –

Hello,

I wonder if you might be able to shine a light on something for me? You mention that the adjustments are arrived upon using the prior attainment of 2020 pupils , the historic relationship between prior attainment and A-Level results in this subject and adjustments to achieve the desired national distribution of grades. It is the last of these I had a question about.

Would the adjustments to achieve the desired national distribution of grades take into account the lack of adjustments made to smaller cohorts. I.e. because the grades would very likely be higher in these cohorts as the CAGs had been either used at face value or given more weighting than cohorts of above 15 in size, cohorts who did have the model applied to them would see more severe downwards adjustments to counter balance that and fit the desired national distribution overall.

Thanks,

Andy

Hi Andy. I don’t think so but can’t be sure is the short, honest answer. In smaller-entry subjects like music where proportionately more CAGs will have been waived through, we’ve seen larger increases in attainment. So my suspicion is that they have worked to an expected distribution just for schools with 15+ entries. But I don’t recall seeing this written down in the technical manual.

Thanks for the response, that makes sense. We were expecting to see some downgrading given what had been reported in advance of results but were very surprised by the number and severity of downgrades in many subjects/schools. We were wondering whether unforeseen things such as that in my query may have helped explain harsher than expected downgrading for cohorts where the model was applied.

It would be great to know for sure – the technical manual is very dense!

Thanks again,

Andy

My reading of the interim report is that national standardisation via “cut score setting” (section 8.2.9) applied to “imputed marks” was applied to all prior attainment matched pupils in the cohort and that then after that small cohorts were allowed to have their grades drift upwards towards their CAGs by the amount specified in section 8.4. The exact wording is “prior attainment matched students only” which seems to include all such to my mind.

My understanding of the process is that, so far, absolutely all deviation from the standardised national picture is attributable to the treatment of small cohorts. It is difficult to see how they could have done it much differently although they had a perfectly workable formula for including CAGs into the picture (the equation under fig 8.3 on page 102) but deliberately chose not to apply it (in their words “to retain the principle of prioritising the statistical evidence for ‘larger’ centres”). Why their asymptotic formula was perceived as not doing that is a mystery to me.

Thanks Richard- really helpful. They seem to give a justification for how they move from the weighting process to the small centre adjustment they actually used on p103 onwards but I’m a bit done in now.

I would like Dave’s confirmation of Andy Case’s 9.44 am comment if that is possible, as these seems to be a fundamental flaw in the parity required of this statistical model.

This is how I see it and Governors are after an explanation. If the Datalab could confirm it would be helpfu.

Hi Jo- just replied to Andy as best I can. Think the reply is there now.

I suspect there has been a mistake regarding prior attainment calculations for EPQ, which is normally taken in Y12.

Was the standard age adjustment done differently for EPQ students (bearing in mind their GCSE APS would have included nearly all reformed point scores last year?).

Our summary shows a prior attainment adjustment lowering the %s a little, BUT our 2019 Y12 cohort had GCSE APS lower than our 2020. We also have high numbers of students and a high L3VA for this course historically.

Is this another travesty of nuance not being able to be catered for in this algorithm

This is what I can’t get my head around. The model uses an age-standardised (or normalised) version of GCSE APS supposedly for England, Wales and NI although they have different grading systems. Schools haven’t been given these values to check.

I think centre historical value added is actually taken account of as described here:

https://twitter.com/Databusting/status/1293849802074214401?s=19

Hi Dan. This is what I thought yesterday. However, the equation on page 93 of the technical manual and the last para of Section 8.2.3 make me think it isn’t. I might think something else tomorrow. Tech manual here https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/909368/6656-1_Awarding_GCSE__AS__A_level__advanced_extension_awards_and_extended_project_qualifications_in_summer_2020_-_interim_report.pdf

Hi Dave,

Which exam board was this example from please? We use three different exam boards and have noticed significant differences in the way they have applied the process.

Hi Sophie. That was from AQA. I think the Edexcel ones are slightly different and the adjustments work cumulatively. Not seen examples from other boards.

How reliable is the prior attainment data? How advisable is it to use KS2 data when 5 or 7 years have elapsed in the interim and student achievements can diverge enormously due to a number of extrinsic and intrinsic variables?

Hi Julian. Really good question. As far as I can see, it will only be used to adjust centres’ historical results if the distribution of prior attainment for the 2020 cohort differs from the average of 2017-2019. So it’ll mainly be used to help determine the set of grades to award at a school rather than the allocation of prior attainment to pupils. It’s probably better than not using it.

Am I missing something? Using the cumulative values in your table doesn’t give the awarded grades. My calculations have one student being graded down from C to D and one being graded up from E to D. The grade up could be connected to your footnote, but that doesn’t explain the graded down student.

We seem to noticing some issues in Edcexel. AQA works out exactly like the about but the calculations don’t seem to work for Edexcel and we end up with 136%. Could you show us how Edexcel work?

It looks like they’d have been better off ignoring the prior attainment of students altogether. For centres with a largely stable intake and A-Level results, the algorithm would only give results consistent with past distributions if that centre has no value added (or subtracted).

What I suppose the algorithm does attempt to do is account for particular cohorts with lots of very strong students compared to previous years. I would have though that this would affect relatively few students, compared to the importance of getting things right for large centres with consistent value added.

Either way, centre-level value added really should be there. Otherwise more deprived areas are penalised once through their historical data, and cannot regain this ground.

It looks like they’d have been better off ignoring the prior attainment of students altogether. For centres with a largely stable intake and A-Level results, the algorithm would only give results consistent with past distributions if that centre has no value added (or subtracted).

What I suppose the algorithm does attempt to do is account for particular cohorts with lots of very strong students compared to previous years. I would have though that this would affect relatively few students, compared to the importance of getting things right for large centres with very stable added value.

The neglect of added value does seem biased to me. Centres with poor GCSE scores coming in already have this baked in to their historical performance and it makes no sense to penalise this again via the prior attainment adjustment.

Should there be an APPEAL? A school with previous Sig+ Subject Level L3VA for a large cohort in a particular course where there has been an enormous reduction in outcomes this year? There is no recourse to mocks as that is not the nature of the course. The appeal would be on the basis of mistakes at Board level with the standardisation algorithm? Referring to section 6.2.3 Re Direct Centre Level Performance?

I welcome your views.

Hi Jo. Just working through the comments received over the weekend. Looks like yours was written well before the appeals debacle yesterday! But yes, I think appeals should be allowed for schools with historically high VA where the prior adjustments have resulted in lower outcomes.

The data used is historic, doesn’t reflect student ability on a level playing field nor their true potential in future final exams. A-level internal coursework, tests and exams were never intended for external assessment and very capable students focusing on high achievement in final exams are crucified in this system.

What weighting is put on Spring 2020 mocks? What data sets are being gathered for each student to allocate points before they are entered into the mixer and ranked according to classmates? This isn’t a unified approach and every school will use different assessments.

Why aren’t internal AS level results being taken into account in England as in Wales? Worst of all since Spring 2020 mocks appear to carry an unfair weighting, many students don’t perform to their true ability in Spring mocks. They’re used as a dry run and wakening up call for many, so can hardly be used to predict capability in final exams. This approach favours some but not other types of students who work differently.

Also mock exams are not a fair marker if the government reverts to Scotland. Mocks are internally set, vary widely among schools, some are in December and others close to May – significantly later. Those sitting a later mock are more likely to have covered the syllabus and are ‘exam ready’ to get a good mock grade. Questions on mock papers are internally set and some schools write difficult mocks to challenge and others set ones which cover the coursework completed at that time which could cover less challenging topics and some mocks are written to give students a confidence boost too. How can widely varying mocks within individual schools and throughout the country be an accurate guide? This isn’t a national standard at all.

Surely UCAS predicted grades are a far more accurate measure than working meaningless statistics. Predicted grades were fairly set before the impact of Covid19 was known and with school names on the line, predictions were more likely to be much more accurate. The disparity of grade prediction between students and schools would be far less this way than the hopeless exercise being used now which only keeps statisticians happy. Has the education sector and government lost all sight of common sense on this?

The horse has already bolted for pupils with grades they are happy with and now enjoying security of a University place. But for many, who’s hopes and dreams have been shattered … what is next for them? Can schools offer Year 14 so they can properly complete Year 13? There are autumn exams but many schools were a long way off completing the syllabus when schools closed and Y11 and Y13’s were turned out to pasture with no on-going support from school. And those taking an autumn exam, how will they be on a level playing field to those of previous years who will now need to prepare for these exams without the support of school, in a short time and after being out of school for so long and with limited resources – hardly ideal. Unless of course parents have a hefty bank balance and can now pay to have them intensively tutored and able to pay for appeals and exam entries which current Y13’s could face paying for?!

It’s beyond belief … and if it wasn’t bad enough, this year’s cohort have been the most affected by a switch to 1-9 grades, more challenging syllabus and exams, limited passed papers to prepare … need I say more.

The world has gone mad. There are winners in this system but many losers too – totally unacceptable. Grades allocations are unfair, their means of calculation is seriously flawed. On a school level, allocations are subjective and exposed to unintentional favouritism.

Also there’s much in the news about grade drops from A* to A or A to B … mmm. But what about those who have been seriously impacted by these algorithms … and I’m talking drops from A to E for all subjects in sone cases. What is their right of appeal? It’s downright disgraceful and these are the students the real focus should be on.

The only way forward is to revert to previously predicted UCAS grades which pupils, teachers, schools and the entire education sector based much more accurate assessments and a year of effort and investment on prior to Covid. At least surely this could be applied to those extremely disadvantaged students who’s current grade allocates bare no reality what so ever to predicted grades – a complete nonsense. Surely UCAS predicted grades reflected true potential, should have been taken into the mix and now used to help those seriously disadvantaged by these disproportionate and idiotic algorithms?

A quick plot of these results shows that it appears to make the grade results look more like a Normal Distribution. Is that the case across the results?

Grade results are not distributed in this way, and the skew varies a lot between subjects.

Is this apparent change in distribution down to the use of an arithmetic mean in the calculations?

Has anyone looked at how different subjects have been affected by the downgrading?

From a quick overview of the way grades have been calculated/allocated it’s certainly skewed negatively and bases performance on an earlier cohort which by no means is indicative of the current group of students. This way of allocating grades is totally flawed … I mean totally flawed! I’m amazed any statistician worth their salts can say these predictions bare any resemblance to reality and to individual students capability. I’m sure subjects vary in their assessment too. The data is historic and doesn’t consider potential. CAG grades are also subjective and often don’t take into account disrupted studies, disability and such in reality (despite the guide suggesting this is taken into account … but how?!). The whole mathematical modelling exercise costing the country months of effort and cost is ridiculous and widely open to interpretation. Media is also focusing on those students that dropped one grade from perhaps A to B. What about those whose futures have been totally blighted by this ridiculous exercise and dropped 4 grades in all subjects for no fault of their own! That’s what the media should focus on and needs to be corrected and doesn’t reflect reality. It’s an academic statistical exercise which is seriously flawed. We’re playing with children’s lives here. We owe it to these students (some marked down by 80%) a more trustworthy assessment and a more robust and well thought out pre-Covid assessment which can only be UCAS predicted grades.

I’m not a statistician but I don’t understand why the “algorithm” has not been based on prior attainment at a pupil level. Presumably virtually all the A level candidates did GCSEs. Will they all have had ALIS predictions? Couldn’t this have been used somewhere in the model? Allocating grades for a cohort based on the pattern of a previous cohort seems to ignore the fact that cohorts are made up of individuals. Why is it not students own prior attainment that underpins their predictions rather than that of completely different people?

I am flabbergasted to hear about the B to U type scenarios. Surely this was bound to happen if there was no link to individual data either ALIS or CAGs or prior GCSEs. This is a shocking abdication of responsibility to make the best predictions for each student as an individual rather than a potential datapoint on a curve.

Everyone knows that results days brings highs and lows. The results achieved are based on efforts at an individual student level. In lieu of the students being able to complete exams, teachers were asked to stand in for them. So there were a few data sets for each individual student.

Data scientists are able to do incredible things, but the approach used appears to be a pretty blunt instrument. Given how important these results are for individual students’ life plans, it’s deeply troubling that the commissioners of the model used found it acceptable to have one with so many flaws.

… well said … although I’m hoping they’ll revert back to predicted UCAS grades myself. Thank you!

Thank you for an incredibly useful article and some fascinating conversations!

I wonder if anyone can shed any light on the prior attainment adjustment as I think I am confusing myself. The table in the article above shows these adjustments as percentages and the overall total of the adjustments is 0%.

However, this isn’t always the case and I can’t find any mention of the adjustment actually being a percentage. I might be missing something but, in a document from Pearson, the prior attainment adjustments sum to – 6.4…….

https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/Support/Post-results%20services/A2222_results_day_support_guide_FINAL.pdf

Am I missing something?!

Thank you!!

I’m glad you’ve raised this as I am equally perplexed by this. In the AQA report the total of the prior attainment adjustments always equals zero. But with all our Edexcel/Pearson subjects the total of the prior attainment adjustments ranges anywhere between 5.01 and 42.1. I just cannot work out what they are doing here? If anyone does find the answer to this please respond here and let us know!

Hi Mary. Thanks for the question. And sorry for the slow response- have had more comments than usual to answer. It seems that Edexcel uses cumulative percentages rather than actual percentages. This tweet from Richard Trimble shows an example: https://twitter.com/RichardTrimble7/status/1294238786600280064?s=20

So the rule for allocating ranked pupils seems to be that, working from A* down to U, you assign the pupil to the current grade unless that would give a percentage of pupils allocated for the grade above the expected percentage.

So in the example, 1st pupil gets A*, but 2nd does not (that would give 7.4% allocated A*, above the expected 5.71%), so 2nd pupil gets A.

Then why are 7 pupils allocated A, when this gives 25.93% allocated at grade A, when the predicted percentage is 25.86% ?

If these are genuine figures from a real school, then what is the rule that decides where the grade boundaries are? The info in this post doesn’t give the complete story.

Hi Howard. I now think there’s rounding to the nearest whole pupil but haven’t updated the post. What I think would make things a bit clearer for schools is for boards to present the 2 adjustments they make: 1) the adjustment based on prior attainment 2) any further adjustments made to achieve the desired national distribution of grades.

The only country, which did not set exams in Europe is the UK.

The whole idea of canceling the exam was stupid.

Germany and other European countries have delayed the exams but never cancelled them.

The model used by ofqual is so stupid.

How on earth you assessed the school history but not the student history.

In the example of A level, the assessment should have been based on the GCSE, AS level and mock exam results.

All of that did not happen, and instead subjective teachers opinion was asked and then the result history of the school.

Please correct me if I am wrong

Interestingly the sector affected most is the selective state schools. Government have seen an opportunity to defame good grammar schools to help with its agenda for getting rid of them!

I can agree with that considering two such schools in my locality … stupidly (apologies for the term) they graded students down themselves not wanting to give inflated results to find the government pulled them down further … double whammy for some students unfortunately and accounting for a 4 grade drop in many subjects!

Please could you explain to me this case

My son results are as followed

GCSE :

13 GCSEs all of them 8 and 9 which means according to the old system, all are A**

AS level in 4 subjects , Has got the maximum grade can be awarded which is 4 A

Mock exams 2020 in January he has got 2 A* and 2A

Results for A level 2 A and 2 B

His teachers and of course us were expecting 4 A*

How did that happen??

We are going to appeal on the ground of his mock exam results which will result in 2 A* and 2 A ,

How can the system get it so wrong

Thank you

thank you all … really enjoying sharing views and extremely useful articles and links … why don’t UK Universities be more flexible too … they’re certainly not at the moment taking into account ridiculous grade drops from these inaccurate modelling results … from A to E!!! It’s obvious isn’t it something is adrift. Apparently Universities are hanging on to the hope they’ll still attract international students at higher fees and lecture to them virtually. Surely this is a year when they could put back profitable international students (perhaps with the support of government) and allow a much greater cohort of UK students to University and look after our own students for once. And in my view predicted UCAS grades should be used … not as subjective and inaccurately modelled as the current system being used … what a joke.

My reading of the Ofqual report is slightly different from yours. They start by carrying forward the profile of grades from previous years. Then they calculate a delta for the change in expected results based on the prior attainment of the cohort. In doing this they they use the average GCSE results of the cohorts for this and the previous 3 years and the national VA matrices. Finally they add this delta (which may be positive or negative) to the profile of grades.

So the result is adjusted for the ability of this year’s cohort. The complaint that it doesn’t reflect the centre’s VA is wrong: the centre’s VA was reflected in the profile of the grades brought forward.

Where the algorithm falls down (apart from relying on an impossible-to-define total ordering of the candidates) is that the adjustment is unrealistically small. This is for two reasons:

1. the calculation of the national VA matrices inevitably results in a lot of smoothing (that’s what national means);

2. it is impossible to predict how many exceptional students there will be in a subject each year or what their results will be.

The end result is that where standardisation is applied, the most able candidates in a subject at a centre get results which primarily reflect what candidates at that centre got in previous years.

At the other end of the rank ordering, there is possibly even greater unfairness, with rounding-down leading to the lowest-ranked candidate getting a U, as Alex Weatherall has explained (https://twitter.com/A_Weatherall/status/1294012623776817158).

What can be done now, apart from lots of appeals? Where a centre had 5 or fewer candidates in a subject, candidates were awarded their CAGs. Where a centre had between 6 and 15 candidates a taper was applied. Full standardisation applied only to centres with more than 15 candidates. Why not use this approach universally? Give the top 5 candidates in each subject at each centre their CAGs and use the taper for candidates 6 – 15. This will produce more grade inflation than has already occurred but not as much as full CAGs. It would save an awful lot of appeals.

Dear Robert,

That what we have been let to believe.

Could you however explain my son’s results:

GCSEs : 12 all together all of them are A* and 5 of them grade 9 which is A**

AS level 4 subjects : Biology A, Chemistry A, Maths A, German A,

A is the maximum grade awarded for AS level.

Mock exams

Biology A*, Chemistry A and Maths A, this was without proper revision, because he was busy doing his interviews.

A level results: Biology A, Chemistry B and Maths A.

This is unfair, because we are certain if my son did the exams as normal he would easily get triple A*

We looked at his CAG and they were exactly the same as his mocks, Biology A*, Chemistry A and Maths A, which was disappointing because the teachers all predicted A* for him in writing and when we met them in parents evening .

I would be very grateful if you could explain to me how possibly this happened and what do we need to do.

Thank you very much

Sorry to hear of what has happened to your son.

The first thing to do is to get his school to divulge the rankings which they gave your son in each subject. This is what counts, not the predicted grades. See https://twitter.com/fiddleplayer01/status/1294294725495848967 for the excellent way in which Eton supply their students with information about their results. If Eton can do it, so can his school.

As well as the rankings, ask the school for the calculated grade %s at each grade for the subjects which he took and the number of candidates. Compare these with the results from the A2 examinations in 2017 – 2019. If the calculated profile differs significantly from the average for 2017-2019, ask the school to demand an explanation from Ofqual.

Using the calculated profile of grades, see where your son slots in. If the grades he was awarded differ from those which the profile implies, ask for an explanation.

Thank you so much Robert.

I will do this steps tomorrow.

We are really devastated

My son is depressed. He does not eat and is isolating him self and do not want to speak to anybody.

So unfair

Dear Robert,

Do you mean They start by carrying forward the profile of grades from previous years for the centre or for the student?

The algorithm has to assess the students and not the centres and schools.

There is bias in the CAG and there will always be biased because the system asked them to rank the grades. There will be different classes and different teachers for the same subject and there were fights between teacher where to rank which student. this should never have happened . the system is pragmatic and should not rely on subjective elements.

I agree … the CAG is totally subjective. Not only that but falling back on mocks is flawed too since varies per subject, when the mock took place (November to May), how difficult the paper was, did it reflect work covered to that point or more difficult parts of the syllabus, it will vary per schools and certainly isn’t a national standard to base student’s grades on. And what about transparency? Students should know what homework, tests etc were used, whether any adjustments have been made and how the ranking is justified. The whole point of exams is to take away subjectivity and a level platform for all students. At least UCAS predicted grades were a value judgement based on much effort, research and opinion pre covid … why isn’t this getting the attention it so rightly deserves?

Hi Robert. Sorry for slowness in replying to your comments- have had quite a fair few to get through! To be clear, my argument is that the *adjustment* doesn’t reflect historic VA at the school. I agree that historic VA is incorporated to some extent in the historic results. I quite like your idea about allowing the top 5 candidates their CAG. It would introduce some fairness. It probably wouldn’t help much with the grade U issue which is caused by a) the prior attainment adjustment and b) the overlaying of the national distribution to achieve the required %s at each grade in each subject. Currently doing a bit of work on this to try and work out the effect it has in practice, particularly for larger centres.

Hi Dave,

Thanks for your reply.

As far as the grade U problem is concerned, it seems to me that Alex Weatherall has hit the nail on the head. Rounding up rather than down, at least at the bottom of the distribution, is a necessary fix to what amounts to a bug in the design of the algorithm.

In all the comments about favouring public schools, it’s perhaps worth noting that the real beneficiaries are the minor public schools: the top public schools such as Eton enter so many candidates in each subject that the vast bulk of their results are subjected to the algorithm, e.g. see https://twitter.com/fiddleplayer01/status/1294574384930226176. The real problem lies with cohorts > 15 in which outstanding candidates are rare. They are the ones who lose the most from the algorithm and where accepting their CAGs would remedy a genuine unfairness.

Hi,

My son got ‘As’ in all the four science subjects in O level. He got ‘A’ in all subjects in As i.e., Bio, Chemistry and Physics in Mock exam, result of which has been sent to Cambridge by the school. But in adjustment of result, he is awarded, ‘D’ in Biology, and ‘Es’ in Chemistry and Physics. I don’t understand this at all and am worried about it. Can any one answer and let me know how to fix this.

The key information which drives the grades is the ranking which the school gave your son in each subject. Predicted grades are irrelevant for cohorts larger than 15 in a subject. You need to find out what these rankings were and how large the cohort was in each subject. You may be surprised (and disappointed) to find that your son was ranked much lower in these subjects than you or he had expected.

Why were averages used and not median values for the three different years? And what are the standard errors as between years? There can therefore be some overlap between grades, whereas the simplistic analysis infers that the separate years are independent data. This is also an untested feature of the analysis. Timeseries of data are rarely un correlated. The staststics used in the

What does a centre have to do to get a prior attainment adjustment of zero?

1) Have students who’s prior attainment is at the 50th percentile nationally?

2) Have students who’s prior attainment is a historical match for the centre?

3) Have students who’s prior attainment matches what the exam board would expect for the centre’s historical results?

I think option 2 is the only fair outcome, but not having centre level VA means this isn’t done. Option 1 would just stretch the outcomes. Option 3 actually penalises schools who teach well, and gives credits to schools who don’t. So do private schools do well because their added value is so small?

Hi Dave,

We enter both Y12 and Y13 students for A-level maths each year so had to put them all into one ranked list. Do you know if the prior attainment adjustment for maths will include the results of the Y12 students from summer 2019 (who are a Further Maths class and as such have higher GCSE Maths grades) or will it just be based on the Y13 students results from summer 2018?

thanks

Dave,

Is it possible that we have missed something in Step 8 of the algorithm? I was struck by a report on the Radio 4 News this evening that the Government had imposed on Ofqual a limit of 2% on the improvement in grades this year (presumably this means separate constraints on the % of candidates getting A/A* and on the % getting grades A* – C).

I don’t like that being imposed as a constraint. I wonder whether achieving that objective is what lies behind the puzzling Prior Attainment Adjustment in your example. The first two paragraphs of Step 8 (section 8.2.8 of the Ofqual report) could be verbal legerdemain to cover up some sort of massaging of the results. What would you do if you were in Ofqual’s shoes and you had just discovered that awarding CAGs to all cohorts <5 and tapered adjustments to those in cohorts of 5 – 15 meant that you had already broken the 2% limit? I know what I would do: reduce the magic numbers 5 and 15. But Ofqual didn't do that. I wonder whether they used Mark Imputation to bring the results back within what they deemed acceptable to Ministers? If they did, the algorithm really is broken.

Dave,

Annex J implies that Ofqual have ignored the leniency for small cohorts in applying standardisation. That’s good. Did the allocation of grades in your school’s example flow directly from the grade profile after applying the Prior Attainment Adjustment? Or did they provide the data for you to be able to apply Steps 8 and 9? If the former, that suggests that the Prior Attainment Adjustment is in fact the aggregate of all the various adjustments to massage the CAGs across the country to a distribution in which there is a 2% increase in grades for non-small cohorts.

It looks increasingly to me as though Ofqual will have to bow to the inevitable and accept that their single standardised grades aren’t acceptable as the definitive results. I rather like the suggestion which I’ve seen that results should be presented as multiple data points. So a certificate would tell you what the candidate’s CAGs were as well as the standardised grades. I would add the candidate’s rank in each subject and the size of the cohort.

Then universities and employers could see for instance that a candidate was graded A* and ranked 6/20 by the centre but was allocated a standardised grade C. That would suggest to me that the centre was inflating the CAGs. But I would be inclined to give the benefit of the doubt to a candidate with a CAG of A* and a standardised grade of C who was ranked 1/20 or 2/20. I would also be able to identify where I was being told the raw CAG because the cohort was small.

Dave most discussions seem to be related to how prior attainment has been used to dictate the grades, and rightly so since there are issues with that.

But a central tenet of Ofqual’s “algorithm” seems to be that teachers would be able to reliably rank students.

In “normal” circumstances I expect that there would be a strong correlation between teacher assessment and examinations. By “normal”, I mean if both students and teachers were aware that teacher assessment and ranking was going to be used prior to starting studies, if subjects had course work that can be objectively assessed and consistent across all students taking a subject and of course if the full two years had been completed.

I expect that in normal circumstances that if there was much variation between teacher assessment and examination if would be partly explained by students having a bad day, or reading a question wrong … so that the nature/faults of the exam system would explain much variation rather than an inability to rank.

But none of those assumptions are true this year. So although Ofqual asked for rankings to be signed off by subject leaders, how have teachers been able to reliably rank their students?

Also does the prior attainment use all GCSE subjects, or is there nuance so say a cohort was collectively strong at Maths on average in their prior attainment and terrible at other subjects, would the prior attainment profile vary by subject. I’m assuming it wouldn’t since that would be complicated.

It’s historic data and doesn’t consider potential in exams several months later. The data at best will be January data and there’s no building into the model contingency for a bad mock (let’s face it many students use the mock as a dry run), nor disrupted studies, nor disability … for that matter not much else. Mock exams vary tremendously between subjects, schools, when they’re taken, what part of syllabus they reflect … need I say more! It’s very unreliable.

CAG grades are flawed … the algorithm is flawed … UCAS predicted grades are a much more robust and realistic predictor which took months to develop by students, teachers, schools and Universities and offers were made on that basis. Surely that’s the only way out of this mess?!

Thank you for this analysis. Where do I find what the school submitted on behalf of its students for this subject n 2020 ?

Hi James, those aren’t figures that are in the public domain – at the minute only the school and the exam boards/Ofqual know this.

Surely by way of freedom of information and appeal purposes this is retrievable? I’ll need it to support our appeal … I’ve no confidence in CAG nor the algorithm … they’re both totally flawed and subjective. I hope common sense prevails and they’ll revert back to UCAS Predicted Grades a tried and tested method for many years and pre covid. Mock exams are certainly not a reliable benchmark at all although will favour some but not others. It’s nothing better than the luck of the draw. Predictions on CAG’s and mocks are not accurate nor fair … UCAS predicted grades took months of work by students, teachers and Universities – involved interviews, personal statements, references etc etc … that’s certainly the only way forward.

Surely there must be historic data comparing teachers predicted grades with exam grades for different past years.

If this data exists it would provide the basis for a much more robust method to predict this years exam results than currently carried out.

Yes … but no one knows how thorough schools have been in pulling this information together … I suspect it depends on how organised schools/pupils are too? And what about those who went to a different school up to Y11? Do their results reflect their previous school and their teachers certainly wouldn’t have had sufficient time to build a proper picture … certainly if they had different teachers in Y13! Not only that but the system favours those that are steady workers … typically girls I think … for boys who can be a bit lazy and balance lots of sport etc, their focus would always be on the final exam an not putting effort into perfectly formed homework and mock exams never intended for assessment. The model fails in having a ‘gut feeling’ element about what the students actual future potential would be … it’s historic and benefits those with good historic data …

Playing with flawed models is wasting precious time and causing more damage for students by the hour. The on-going academic juggling of flawed algorithms, subjective CAG predictions, reliance on unrepresentative non standardised mock exams is flawed and this all needs to stop. It’s nothing better than trying to repair a damaged engine by topping up oil, adding a new battery, a new water pump and what ever else … it can never be fixed if fundamentally damaged and the underlying cylinder block was cracked all along. The whole system and saga needs to head for the scrap yard and a new more suitable way found to resolve this. Predicted UCAS grades for me please.

I’m wondering whether your take on centre Value Added is correct. The important bit of the OFQUAL formula for Pkj (chapter 8 step 6) is the bracketed factor of rj the right. For most centres, rj is close to one (most students do have prior attainment data) so Pkj is approximately equal to the sum of the three terms in the bracket. OFQUAL write this as: ckj + qkj – pkj. Alternatively: qkj + (ckj – pkj) i.e. predicted fraction at grade k (national pred) + (difference in actual and national predicted historic fractions) for the centre in question.

The difference term gives the contribution to value added at each grade and the sum of all 7, weighted by the number of points per grade, gives a common value added measure. Calculating Pkj in this way gives the same VA for 2020 as the historic data for centres with no unmatched students – at least at step 6 of the algorithm.

Hard to make sense of in this typeface – sorry about that. I might upload a nicer version to our PTNC forum which allows font variation. (Physics Teaching News and Comment)

I suspect our simpleton Ed Sec thought that by using the most complex (but flawed as it turned out) of the algorithms on offer it was bound to rectify flawed data. Looking at the example above I can’t believe that the 2020 cohort would be that different from the historical data unless there were special circumstances. They would have been better off using the raw historical data as a guide for moderation which should have been done by schools. At least it would have included the school value added element. There is no doubt that many students at A level and even more at GCSE have been over-graded to get them over grade hurdles. but it’s human nature to want to give your students the best possible start in the world.

All of this continues to give statistics a bad name which is usually caused by failure to interpret outputs correctly. However in this case I don’t think the input was understood correctly.

Hi I am not a statistician but can someone tell me how SEND students would have be treated in this? If a student had to have 25% additional time how would a school have “added this in as a factor”

Hi Julie. Schools were asked to come up with grades for their pupils that they would most likely have achieved had the exams gone ahead. As such, my understanding is that it would have been up to schools to take into account the knowledge that a particular pupil would have had 25% additional time to do a certain exam in setting those grades.