With exams being cancelled again in 2021, concerns have resurfaced over there being rampant “grade inflation”.

This was thought by many to be a perennial problem throughout the nineties and noughties as GCSE and A-Level pass-marks increased year-upon-year . Yet, when the Conservatives came to power in 2020, this was something that they vowed to end.

Indeed, some argued it was this obsession over avoiding grade inflation and maintaining standards that ended up leading to the disaster we saw with the awarding of examination grades last summer.

But how have GCSE standards really changed over time? This blogpost takes a look.

How can we do this?

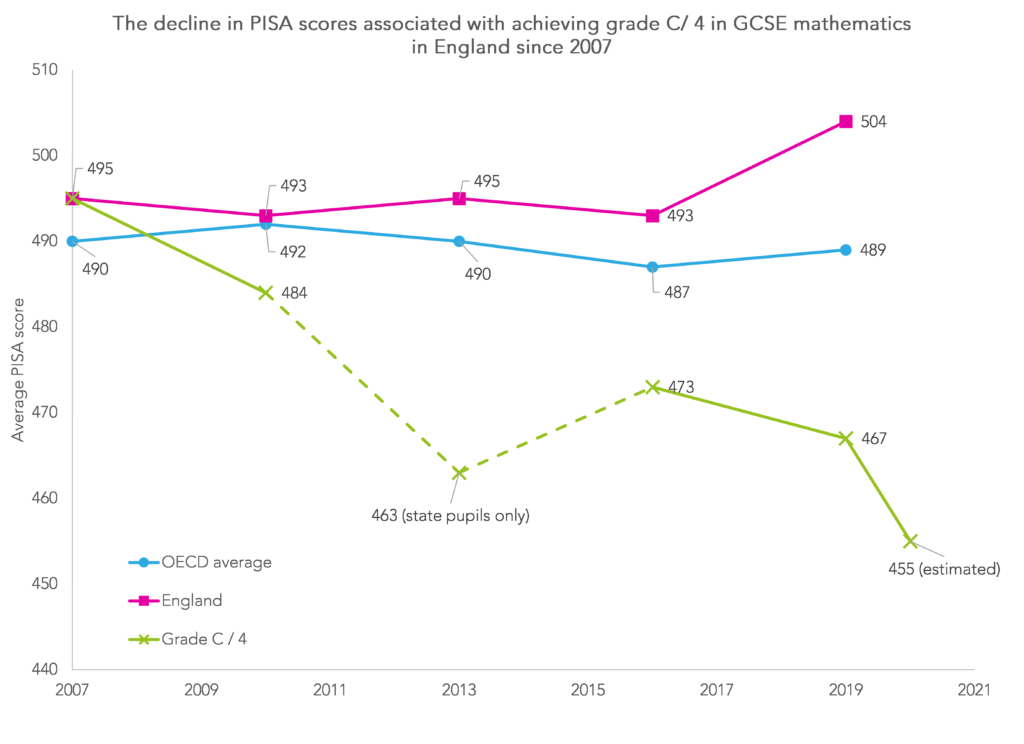

To examine grade inflation over time I look at average PISA mathematics scores by GCSE mathematics grades, covering examinations taken between 2007 and 2019. PISA is taken just six months before GCSEs, and provides an independent benchmark that is meant to be comparable over time (and hence not affected by problems of grade inflation). That said, readers should keep in mind some of the caveats I have written about PISA previously.

This takes us through to 2019. But we know a lot of grade inflation also occurred last year due to the disaster that came with cancelling examinations. I have produced a rough estimate of the impact that this has had in terms of PISA scores and so also include this in the results (gory details of how I came up with this estimate can be found here).

Together, this allows us to look at changes since 2007 in the “value” (in terms of PISA points) of England’s GCSE “standard pass” (grade C in old money, grade 4 in new money).

A sustained fall in value

The chart below [1] provides the headline results, comparing average PISA mathematics scores for those who achieve England’s 4/C grade standard pass in mathematics (green line) to the average for England as a whole (pink line) and across all OECD countries (blue line).

There has been a clear and sustained fall in the value of England’s GCSE standard pass (grade C/4) over time. Back in 2007, hitting the floor target (grade C) was equal to the OECD average (495 points). Yet this value has got gradually eroded away, down to around 470 after Michael Gove’s time in charge and down to around 455 points for a grade 4 in 2020.

To put this into context, the OCED would equate this 40-point fall in the value of England’s floor target between 2007 and 2020 to a drop of more than one whole year of schooling.

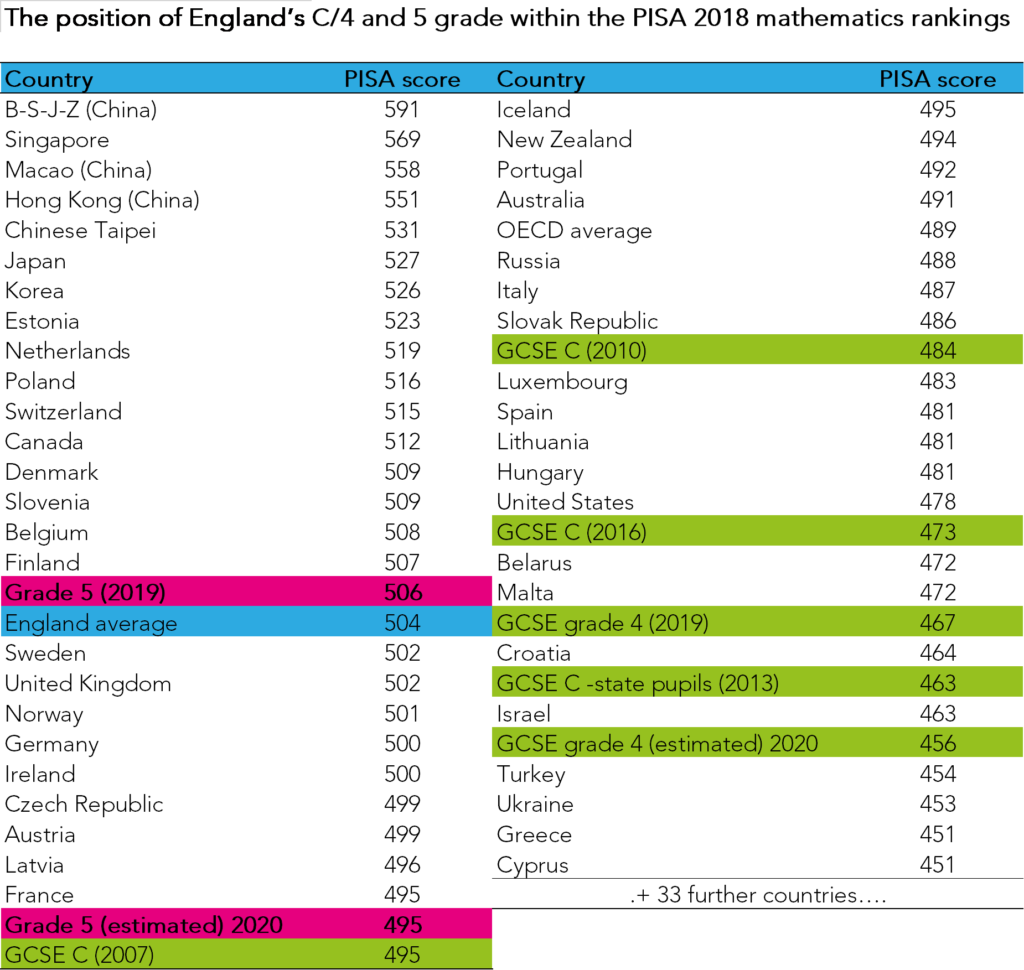

The table below provides further contextualisation of these results. This takes the PISA 2018 mathematics rankings and inserts the value of England’s floor target since 2007 (for each year with data or an estimate available). I have also thrown in the “value” of grade 5 in 2019 and 2020 (estimated) for good measure.

Children who got a grade 4 in mathematics in 2020 had roughly the same skills as the average young person in countries like Turkey and Ukraine. This is around 16 places lower in the PISA rankings than a child who got a C grade back in 2007 (roughly equivalent to countries like Australia, New Zealand and France).

The table also illustrates how a grade 5 in 2020 now has almost exactly the same value as a C grade did back in 2007. Post-pandemic, this might justify the 5 grade becoming the new floor target young people are expected to achieve.

A tale of two policy mistakes

The devaluation of England’s expected standard has really stemmed from two key mistakes.

The first was the miscommunication of what the expected standard was when the new 9 to 1 grading system as introduced – and whether grade 4 or 5 should be considered the “pass” mark.

The second was in the response to the cancellation last summer, which led to the eventual reliance upon (inflated) centre assessment grades.

Now, only time will tell whether we will see yet more grade inflation this summer, as some suggest.

But, if we do, then a conversation may be needed as to whether existing floor targets continue to hold sufficient value.

1. Grade C figures in 2012 based upon state school pupils only (illustrated by dashed line). Data for 2020 estimated from change in the grade distribution between 2019 and 2020. Year running along horizontal axis refers to the year GCSEs were taken by the PISA cohort.

When letter grades were replaced with number grades, the government deliberately decided not to map them across. Initial plans were that a 5 would be the grade needed for a good pass. This was changed when the numbers of pupils needing resits with GCSE grade 4 and below was simply too high for colleges and schools to cope.

What we see is that the government has reduced the quality of a “good pass” at GCSE by making this a 4 instead of a C and that a 5 is a better equivalent for a C.

Personally I wish people would give our kids a break. They work hard for their accomplished grades. I re-sat my GCSE Sciences last year and was amazed at how much is now involved, we expect our kids to do on average 8+ subjects and then trivialise their grades. Let’s give them the praise they deserve, they get there grades because they work hard or naturally gifted.

An interesting analysis, for sure. I can’t quite figure out how this sits with the results of the National Reference Test, in which significantly more of the 2020 cohort got a grade 4 than in 2017? My understanding is that this performance is measured using the same set of questions each year – so this does suggest that (the sample of students in) this cohort did do better in attaining Grade 4 than those in 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/910252/NRT-Summary-2020.pdf

Thanks. An interesting point. The latest PISA tests were done in 2015 and 2018, so cover a slightly different period to NRT 2017 to 2020. This could be part of the explanation…….

It looks like most of the ‘PISA scores per grade’ appear to be lower over time, including A* and A if you look at 2006 and 2015…

https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/average_pisa_scores_by_gcse_grad

But is any of that a statistically SIGNIFICANT change? We can’t tell. At the moment, we’re basically just looking a numbers and seeing that they appear to be different.

Should we focus ONLY on grade C? Perhaps not, otherwise it risks being a bit misleading.

Nevertheless, imagine the tabloid-style treatment… ‘PLUMMETING PISA SCORES for the TOP GRADES! People with A* grades had got 627 scores in PISA as of 2006 but 608 scores in PISA of as 2015! My goodness, what an apparent difference – 608 is lower than 627! SHOCKING implications to our STANDARDS OF SUCCESS!’

As a history teacher I’ve always felt it’s a hidden scandal what has happened to percentages needed for approximate grade boundaries since the introduction of 9-1 grades. The drop is dramatic.