I’ve written several pieces over the last few months on how Key Stage 5 subject choice relates to attainment at GCSE. And there’s still lots to unpick.

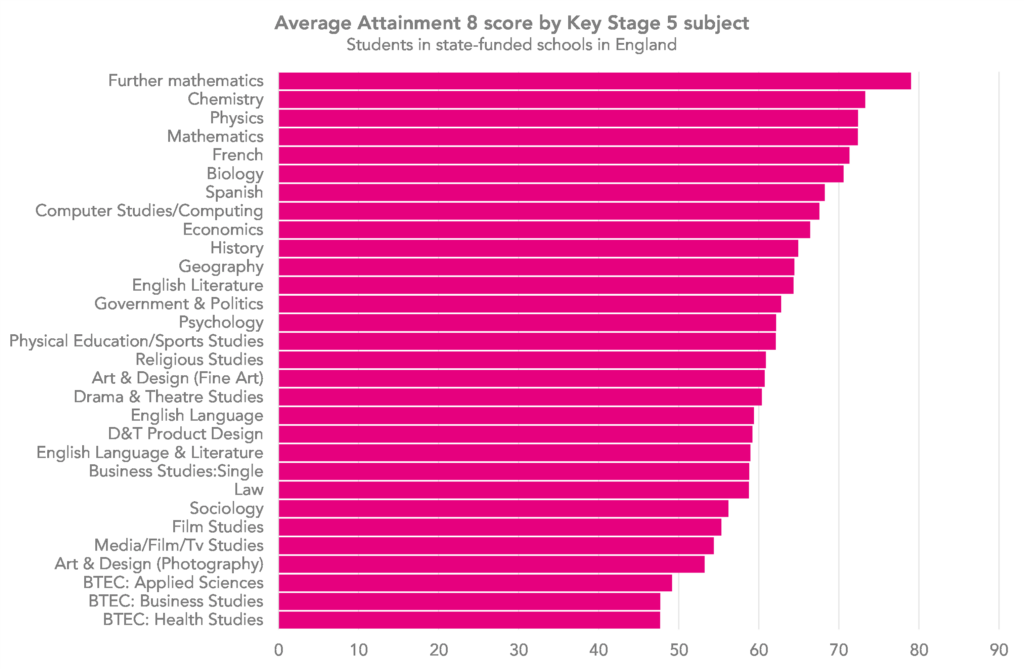

As we saw in previous posts, the prior attainment of KS5 students does vary quite a bit by subject. Regular readers will be painfully familiar with the chart below, which has already appeared in several posts.

A-Level further maths students have the highest average Attainment 8 score at 79, and BTEC health studies the lowest at 48.

This means that further maths students achieve the equivalent of a grade 7.9 in each of the qualifications that make up their Attainment 8 score, while health studies students achieve the equivalent of a grade 4.8.

What’s not clear from the chart is why these differences occur. Are high achieving pupils just more likely to want to study subjects like further maths, chemistry and physics than their low attaining peers? Or would pupils with lower prior attainment like to choose those subjects, but aren’t able to because they don’t meet the entry requirements?

Or perhaps the answer is the usual one – a bit of both.

In this post, we’re going to use data from the National Pupil Database to try and unpick whether entry requirements for some A-Level subjects tend to be higher than others.

The set up

I’ll start by admitting that there’s no way to know for sure what schools’ and colleges’ entry requirements are without asking them and / or scouring their prospectuses. And I haven’t done that.

Instead I’m going to see what we can deduce about entry requirements from looking at the data held in the NPD.

I’ll focus in on those A-Levels that have an equivalent GCSE. These include a range of subjects like English, maths, the science, languages, humanities, art and design, design and technology, music and so on. I have omitted any subjects with less than 4,000 GCSE entries from pupils in state-funded schools.

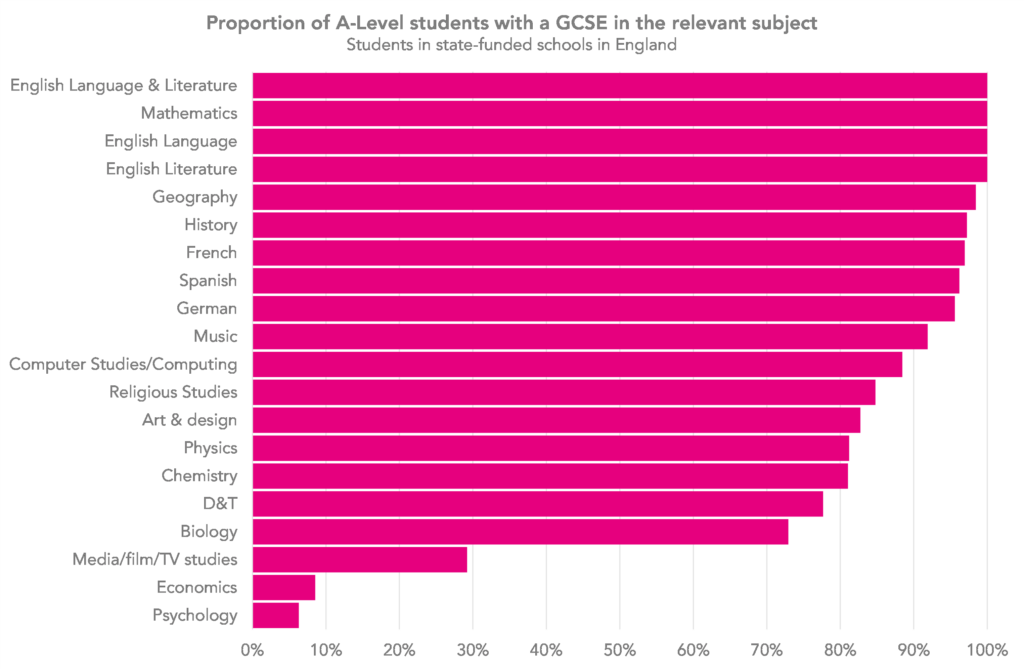

One thing we can say from looking at the data is that holding a GCSE in the relevant subject is often an entry requirement for A-Level. As shown below, in some of these subjects nearly all entrants hold the relevant GCSE.

Obviously this is to be expected for the compulsory GCSE subjects, English and maths. But it’s also largely the case for geography, history, the languages and music; more than 90% of A-Level students in these subjects hold a GCSE in the relevant subject.

While the majority of those taking A-Levels in art and design, religious studies or D&T have a relevant A-Level, it does not appear to be such a universal requirement as, for example, GCSE geography is for A-Level geography.

And for some of the less widely taken GCSE subjects, like economics, psychology and media/film/TV studies, the relevant GCSE does not appear to be a requirement at all.

Both art & design and the sciences are worth a closer look.

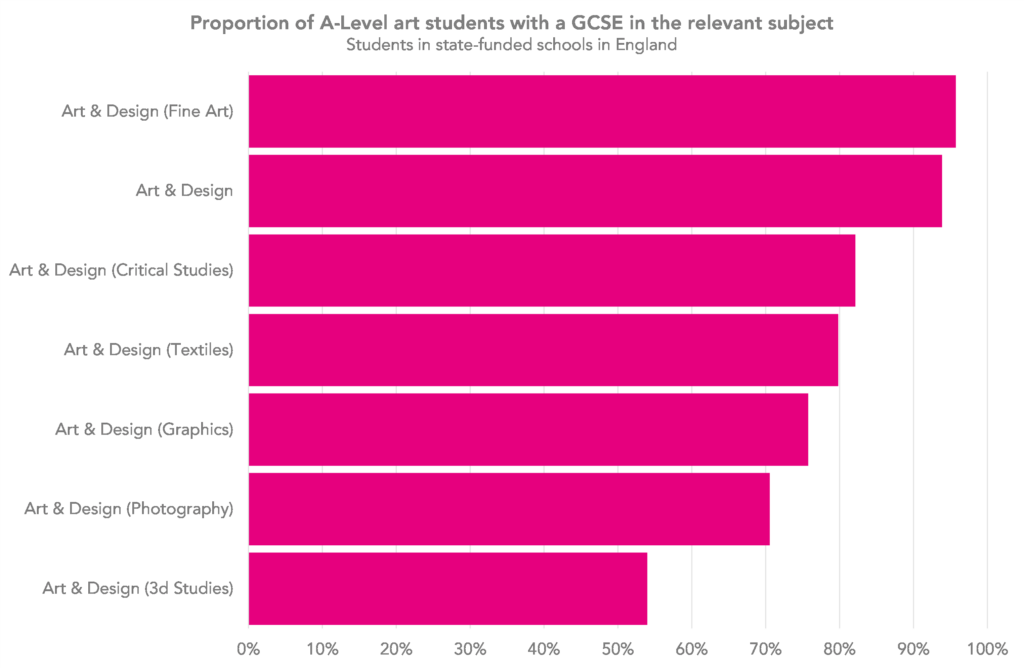

In the original chart, we showed the data for all art & design A-Level subjects. The chart below breaks it down into individual subjects.

This shows that the low proportion is driven by students of A-Level subjects such as art & design (3D studies) and art & design (photography) that do not necessarily have a strong link to GCSE art & design. On the other hand, more than 95% of students of A-Level art & design, and art & design (fine art), hold a GCSE in art & design.

Turning to the sciences, the original chart showed the proportion of students with a GCSE in the relevant single science subject. Virtually all of the remaining students held combined science GCSEs.

Although a significant number of pupils did progress to A-Level science from combined science GCSE, triple science GCSE was the route taken by the majority of biology, chemistry, physics and computer science students: 81% of those entering A-Level physics held a relevant single science GCSE, as did 81% of those entering A-Level chemistry, 88% of those entering computer science, but just 73% of those entering A-Level biology.

What can we deduce about grade requirements?

Again, we can’t be sure whether schools and colleges have entry requirements around GCSE grades just from looking at the data. And anecdotally, those that do can vary quite a bit.

But what we can do is look at the GCSE grades of those students who do go on to enter A-Levels, sticking to those A-Levels in which the vast majority of students also took a corresponding GCSE.

The chart below shows the cumulative proportion of students with a grade 7 or above, 6 or above and so on, in the relevant GCSE subject.

Virtually all of the students taking A-Levels in the STEM subjects have at least at grade 6 in the relevant GCSE.[1] The same goes for language students. So it’s probably fair to assume that most schools and colleges require at least a grade 6 in these subjects. It may well be that the entry requirement is a grade 7, but those with a grade 6 are accepted in some circumstances.

In the remaining subjects, relatively few students had achieved a grade 6 in the relevant GCSE subject, but virtually all had achieved a grade 5. So again, it’s probably fair to assume that most schools and colleges require at least a grade 5 in these subjects – a grade lower than for the STEM subjects and languages.

Having said that, I should note that we’re only looking here at students who complete the relevant A-Level – it may be the case that some students with lower GCSE grades *start* A-Levels, but drop out before the end of the course.

Any other requirements?

The majority of students studying a STEM subject at A-Level achieved a good grade in GCSE maths. 97% of physics students achieved at least a grade 6, as did 94% of chemistry students, 89% of computer science students and 86% of biology students.

This may indicate that some schools also require at least a grade 6 in maths for entry to some A-Levels, physics in particular. Although it may be simply be that those who achieve strong grades in science GCSEs also tend to do well in maths.

We’ve written before on the question of whether schools require students of A-Level physics and computer science to take A-Level maths as well. While we concluded that this doesn’t appear to be a requirement in most schools, it is very common for students to take maths alongside these subjects.

Are different entry requirements justified?

What we’ve seen in the data does seem to indicate that some schools and colleges may be setting higher entry requirements for A-Levels in languages and STEM subjects than for other subjects. And access to science A-Levels is further complicated by the existence of different options at GCSE.

So are any schools and colleges that do set higher entry requirements for STEM and languages A-Levels justified in doing so?

There’s certainly evidence to suggest that they are. Some subjects appear to be graded more severely than others at A-Level, and the STEM subjects are top of the list. Languages have also tended to be severely graded, although this has been reviewed recently.

Given the relatively low chance of achieving strong grades in some subjects, it’s understandable that entry requirements should be set above those of subjects that are less severely graded.

But it does all contribute to the perception that some subjects are more difficult than others. So if we want to widen participation in languages and in STEM, perhaps we need to look again at grading severity.

[1]: For biology, chemistry and physics, we use the grade in the relevant single science GCSE if taken. If not, we use the grade obtained in double science GCSE.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Even though Natasha is clear she hasn’t done the research, here’s a recent Twitter poll (n=620, not balanced sample, likely to be responses by actual Maths teachers) of A Level Maths entry requirements https://twitter.com/mr_man_maths/status/1650943328555266061

Thanks Adam, this does seem to back up my conclusions based on the data to some extent. But on the other hand nearly a third of responses say they only require a grade 6… so perhaps not! Would be interested to see the results of any similar surveys in other subjects.

Thanks Natasha for an interesting article. It’s difficult to draw conclusions about relative subject difficulty at A level because of the effects of a) choice and b) differential correlation among the subjects, as I’ve explained here: (https://www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/Images/374638-the-effect-of-subject-choice-on-the-apparent-relative-difficulty-of-different-subjects.pdf). It might be quite reasonable to set different ‘bars’ for entry to A level if there are reasons to believe that GCSE results are likely to be less strongly related to A level results in some subjects – for example because the content and skills are more different at A level. Finally I’d like to mention some recent work by my colleagues that is an interesting complement to yours, looking at progression from GCSE to A level in the same subject, broken down by gender. https://www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/Images/674348-progression-from-gcse-to-a-level-2018-2020.pdf

Hi Tom, thanks so much for your kind words and for the links to other research in this area. The progression broken down by gender looks particularly interesting, I will be having a read as soon as I get a spare moment…

Hello Natasha,

Interested in speaking to you on this topic with a personal / regional perspective

Hi Lisa, would be very happy to have a chat. Drop me an email at educationdatalab@fft.org.uk and we can take it from there.