Many schools collect test score data across a range of subjects on a regular basis. These data can then be used to try to predict how well a student should be doing in a subject in a year’s time.

It perhaps seems obvious for schools to base such predictions on the most recent test score data available within a given subject. For instance, to predict pupils’ achievement in English at the end of Year 8, one would perhaps intuitively use their scores on an English test taken at the end of Year 7. This – we believe – is what many schools do.

Interestingly, however, there may be better measures available to do this job.

Maths is better than English at predicting future English performance

To interrogate this issue, I used data from one reasonably large MAT. This is part of a Nuffield Foundation-funded project using data in the National Institute of Teaching’s (NIoT) teacher-education dataset. The broader aim of this project is to develop a better understanding of the impact that teachers have on their pupils’ outcomes, meaning it is important for us to have a detailed understanding of the properties of the test measures collected within our sample of schools.

My goal was to look at how well one can predict their Year 8 pupils’ end-of-year English test scores from information the MAT holds about the pupils at the end of Year 7. This included:

- End of Year 7 English test scores.

- End of Year 7 Maths test scores.

- Key Stage 2 Reading scores.

- Key Stage 2 Maths scores.

I assessed how well a previous test can predict Year 8 English results by looking at correlations. If a prior test could perfectly predict Year 8 English results, then the correlation would be 1.0; if there was no association then the correlation would be 0. In practice, the correlation will always be somewhere between 0 and 1, and the closer to 1 then the better the predictive power.

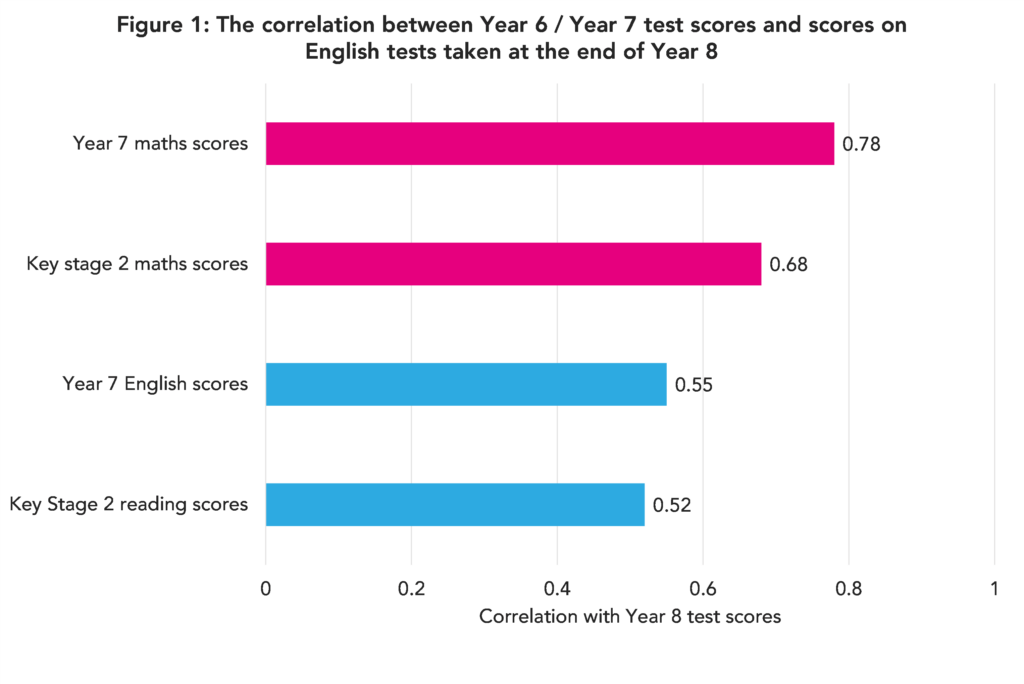

Figure 1 presents the correlation between each of these four “predictor” tests and the end-of-Year 8 English test of interest.

The results may come as a surprise to some.

It is actually pupils’ performance in MATHS at the end of Year 7 that has the strongest correlation with Year 8 English scores (correlation 0.78).

In fact, even maths scores taken at the end of Year 6 (Key Stage 2 SATs) are more strongly associated with Year 8 English test scores than English tests taken at the end of Year 7 (correlations of 0.68 versus 0.55).

A potential explanation is that mathematics test scores typically contain less measurement error than English tests (i.e. they are less susceptible to random error arising from the judgement of the marker). This then makes them particularly useful in predicting future outcomes, leading to this somewhat counterintuitive finding.

Are Key Stage 2 SATs king?

While the Key Stage 2 SATs often get a bit of a bashing, they are a useful source of information freely available to secondary schools.

An interesting question, then, is how much additional predictive value do further test measures offer?

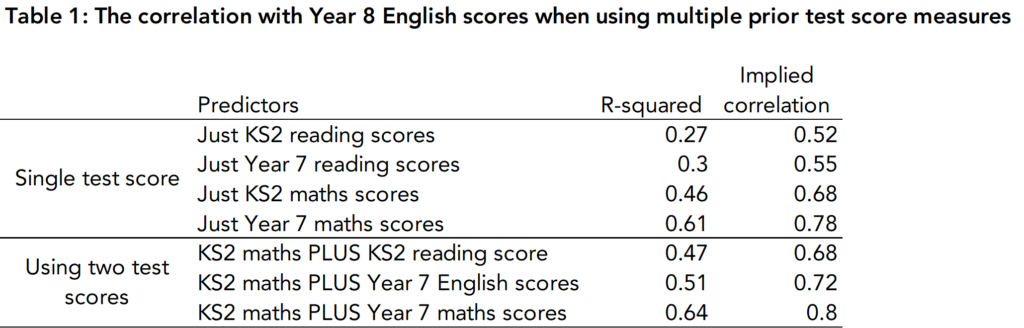

Table 1 provides some evidence on this matter. The top four rows illustrate how well one can predict end-of-Year 8 English scores from a single test score (end of Year 7 English or maths scores, and Key Stage 2 English and maths scores). The bottom three rows then demonstrate how much the predictions made off the basis of Key Stage 2 maths scores are “improved” by adding in information from the three other tests.

As Table 1 demonstrates, Key Stage 2 maths scores do quite a good job at predicting end-of-Year 8 English scores by themselves (correlation = 0.68). Adding in Key Stage 2 reading scores does not budge this (i.e. the correlation is still 0.68), while adding in end-of-Year 7 English tests lead to only a small improvement (correlation = 0.72); in fact, adding in end-of-Year 7 maths scores do a better job (correlation = 0.80).

What are the implications for schools?

These results have two implications for schools.

The first is that they might reflect on whether they are currently using the data they hold to predict and monitor pupil progress in the optimum way. Such predictions are likely to be better when they do not draw only upon the most recent data point in a specific subject alone.

The second is with respect to the amount of testing done, particularly doing so on a termly basis. Sam Sims has suggested that half-termly data drops are adding lots of workload without useful information. Testing has learning benefits in itself and may help pupils and teachers identify specific learning gaps that they may need to address. But if the primary goal of these tests is to track pupil progress, it is likely that a twice-yearly assessment (or possibly even just a single annual assessment) will suffice.

This is a fascinating study but I think there are addional reasons why Y6 maths results cirrelate better than English with Y8 English. Maths tends to be a more binary subject than English. Students fequently do something in maths that is either right or wrong. Feedback is also binary leading to internalised feelings about how good one is at maths – or not. That follows through to adulthood where people are more likely to say ‘I am poor/good at maths’ than they are at Englsih skills.

Nothing breeds success like success or breeds failure like failure. And it radiates outwards! So my question is: is the stronger correlation for KS2 Ma/Eng simpy a product of the internalised feedback of ‘good at’ or ‘bad at’ transferring across the curriculum?

This is a rather narrow assessment of usefulness of what assessment adds. No measurement of wider wellbeing or progress (of students or indeed teachers under the same deprofessionalising testing cosh). A better blind metric would be where a cohort that had no testing and teachers allowed to teach to the needs, pace and development of the individual child compared to the regime of a plethora of testing and helicopter judgement rather than developing self worth and self initiated engagement and reward; and teachers able to focus on the child in the moment. We underestimate the effect of removing joy from teaching and learning and plenty of evidence that testing contributes to the cost side of the equation and rather poorly researched benefits of structured relatively frequent assessment. In short the negative feedback of assessment damages more than we gain from ever more directed teaching, for student, teacher and parent.

Interesting reading. I have seen elsewhere that correlations are higher when joint scores/results are taken into account to predict score/result in a single subject. So mean key stage 2 score across all tests is better than a single test as a predictor for score in a single subject a year or two later. (Maybe I read this in the (bad?) old days of Key Stage 3 SATS.)

Hi Rob. Yes, that’s exactly right.