Being a teenage parent brings several challenges. For those in education, it will bring a disruption to learning and educational progression. Yet it may also lead to young people leaving the education system at a relatively young age, to deal with the financial, social and health burdens of becoming a parent. This may be a particular concern for high-achieving young people who become young mothers and fathers, whose sudden parental responsibilities may lead them to not fulfil their early academic potential.

In my on-going Nuffield Foundation project, I am exploring the later life-time outcomes of children who obtained top Key Stage 2 test scores, and how this varies across those from different socio-economic backgrounds. This blog presents estimates of how likely high-achieving young women are to become teenage mothers. The full working paper on which this blog is based can be found here.

Data

The study draws on ECHILD (Education and Child Health Insights from Linked Data); data matching information from the National Pupil Database (NPD) to Health Episode Statistics (HES). I analyse data on hospital contacts made between age 11 and 20 from three school cohorts, born between September 2000 and August 2003. You can find out more about the ECHILD data on the ECHILD website.

The outcome I focus on in this blog focuses on teenage motherhood (rather than teenage pregnancy). This is because the ECHILD data is based on hospital records, and thus mostly captures successful childbirths. As the data does not include information on terminations, the data is best considered an indicator of completed pregnancies (i.e. giving birth to a child) rather than of becoming pregnant per se. It also means one can only make inferences about teenage motherhood, and not fatherhood.

Sizeable socioeconomic gaps

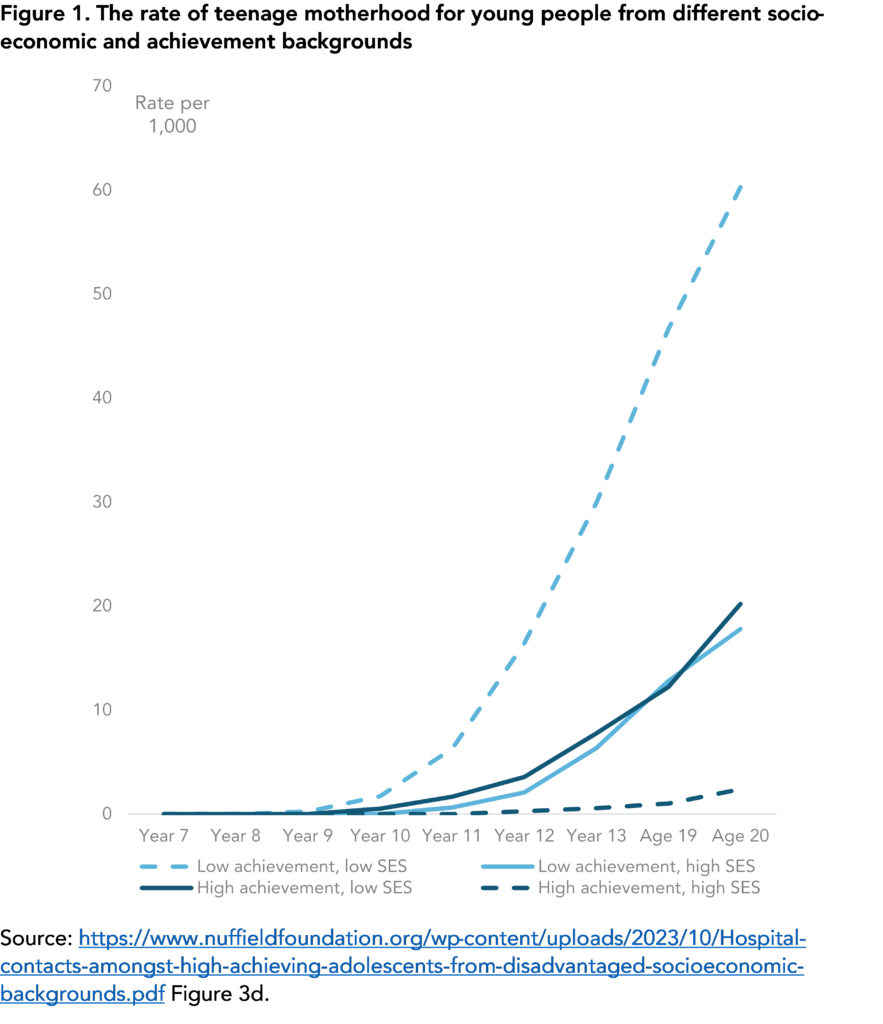

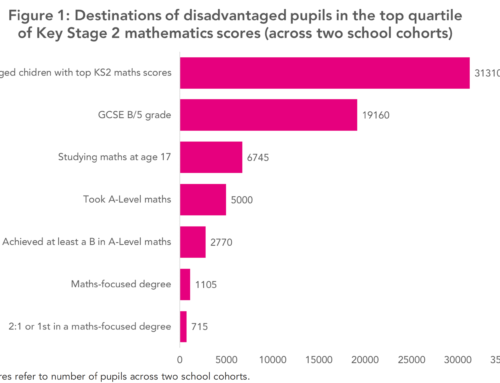

The main findings are presented in Figure 1. This presents our estimates of the number becoming a teenage mother by age, per 1,000 women. Results are presented for four groups:

- High Key Stage 2 scores, disadvantaged socio-economic background (solid black line)

- High Key Stage 2 scores, advantaged socio-economic background (dashed black line)

- Low Key Stage 2 scores, disadvantaged socio-economic background (dashed grey line)

- Low Key Stage 2 scores, advantaged socio-economic background (solid grey line)

The results are striking.

For low achieving, disadvantaged young women there is a sharp increase in teenage motherhood from the mid to late teenage years. The rate increases around 10-fold, from around 6 per 1,000 women in Year 11 to 60 per 1,000 by age 20. This is by far the highest level, and sharpest increase, out of any of the groups considered.

At the other extreme sit those young women with strong Key Stage 2 scores from the most advantaged backgrounds. At age 20, they become mothers at a rate of around 2 per 1,000 women – close to the rate that low-achieving disadvantaged young women become mothers in Year 10 (age 14/15).

In-between these two extremes sit the other two groups, where the trajectory is very similar. This indicates that high-achieving young women from poor backgrounds become teenage mothers at a similar rate to low-achieving young women from the most advantaged backgrounds. This increases from around two women per 1,000 in Year 12 to around 20 women per 1,000 by age 20.

We note in our working paper that these differences should be interpreted with a degree of care. And – due to a methodological challenge known as Kelly’s paradox – the exact magnitude of these socio-economic gaps are captured with a degree of uncertainty. Our central estimates nevertheless continue to suggest that initially high-achieving young women from poor backgrounds continue to become young mothers at a higher rate than their equally able but more socio-economically advantaged peers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings highlight the critical intersection between academic achievement and socio-economic status, particularly for young women. Teenage motherhood will cause significant disruption to high-achieving disadvantaged young women’s education, making it challenging to obtain the qualifications needed for better job prospects. This interruption, along with limited opportunities for skill development, may then trap these young women in a cycle of disadvantage. It is therefore crucial that tailored career guidance and personal support is provided to low achieving young women, particularly those from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, to help them understand the full range of options available to them. Likewise, support systems that provide educational resources, childcare assistance, and career guidance may also be needed to help this group to navigate the complexities of early parenthood.

Really interesting piece of work – I really enjoyed reading the study.

Looking at the method, I can see socio-economic status has been measured by amalgamating IDACI and FSM status at three points in time – but I am pondering whether “socio-economic” is the right description here – is that what we are describing in its entirety, or is it a a scale of disadvantage/deprivation? For me, “socio-economic” also takes account of parent/carer occupations too (e.g. using NS-SEC) – I am not sure that this information is easily available to match with the NPD and Health records?

Where the focus is on advantaged/disadvantaged, I think that is more clear cut. I have got a question about that too though – are we also sure that “most-advantaged” can be measured using IDACI and lack of FSM eligibility alone – or was another variable factored in here to differentiate between “most advantaged” and “least advantaged”?

Thank you again for a great piece of work and these insights!

Thanks Stephen. Yes, I agree. There is only limited information about SES in NPD/ ECHILD. We’re effectively limited to observing whether a child receives FSM over their school career and the IDACI score of the area they live in (so not a measure of specific family/ carer circumstances). And yes, a low IDACI score could mean “least disadvantaged” rather than “most advantaged”.

Yes! Agree. Like Dave says, we are somewhat limited to what is available in the data. This paper may actually be of interest to you on this topic! https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10181779/1/Measuring%20parental%20income%20using%20administrative%20data.%20What%20is%20the%20best%20proxy%20available%20.pdf

I also enjoyed this piece of work. On the face of it, these differences are stark. I have worked for an LA which had a high rate of teenage pregnancy, and my experience has been that for some low-achieving young women from disadvantaged backgrounds (though not measured as scientifically as here), becoming a mother was the thing which gave them an incentive to achieve more highly. Without a child, for whom they often felt a great love, and desire to be a good role model, they had little to live up to. So in my experience, there is a complexity about this issue which might say that even with the undoubted disruption to their education, for some young women, supported in the right way, this might be more positive than initially meets the eye.

Thanks Claire. This is a really interesting point! I actually wonder if this might be a hypothesis we can test in these data. How do those that became young mums go on to do academically compared to observationally similar young women who did not…..

Something for me to put on the to-do pile!