Research has shown pupils compare themselves academically to their school peers. For those in grammar schools, this will mean comparing themselves against a disproportionate number of high-achieving pupils. Studies from the US have suggested that this may increase the academic pressure on young people who – in such a high-achieving environment – feel they need to “be the best of the best”. This may lead some young people to overextend themselves, undermine their feelings of self-worth and – ultimately – impact their mental health.

While much has been written about the pros and cons of grammar schools in England, its links with young people’s mental health have been somewhat underexplored.

In a new working paper published today I therefore explore this issue. This is the third paper from my Nuffield Foundation project exploring the outcomes of high achieving children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. I’ve already blogged about my findings from the first paper and second paper.

E-CHILD data

The study draws on data from ECHILD (Education and Child Health Insights from Linked Data). I analyse data on hospital contacts made between ages 11 and 19 for one of the following reasons from three school cohorts, born between September 2000 and August 2003:

- Alcohol or drug misuse

- Eating disorders

- Self-harm

- Personality disorders (e.g. bipolar, conduct disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder)

- Mental health issues (e.g. anxiety, depression)

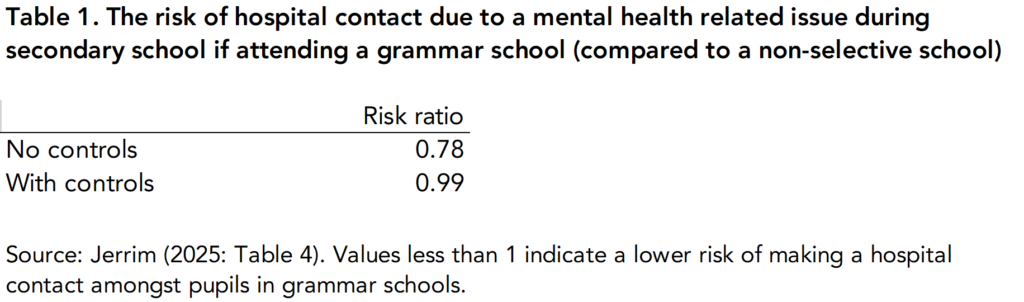

The headline results are presented in Table 1. These are “risk ratios”[1] – the chance being admitted to hospital if attending a grammar school relative to the chance of being admitted to hospital amongst those attending non-selective schools. Values less than 1 indicate that pupils attending a grammar school are less likely to make contact with hospital due to a mental health issue than their peers at non-selective schools.

If one looks at the raw differences (no controls) one can see that grammar school pupils are 22% less likely to contact hospitals due to mental health related issues than their non-selective peers.

Of course, pupils that attend grammar schools tend to be higher achievers and disproportionately from more advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. Once such factors have been controlled, this difference all but disappears. In other words, conditional on their intake, there is no evidence that attending at grammar school is linked to contacts with hospitals related to mental health.

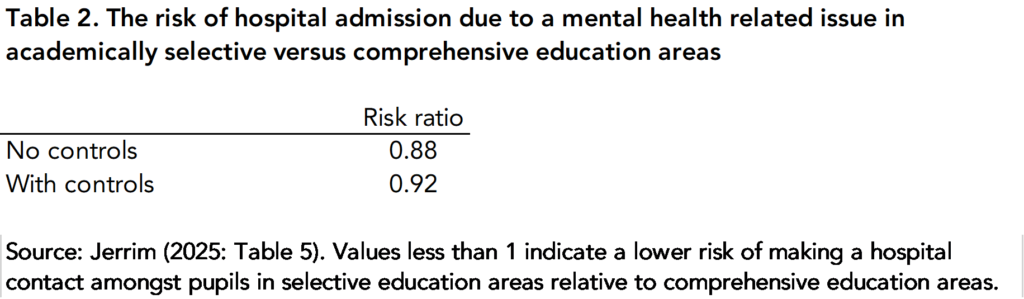

How about if we compare comprehensive and selective education areas in England more generally?

Overall, differences appear small and – if anything – suggest hospital contacts related to mental health issues are slightly lower in academically selective parts of the country. When no controls are included in the model, the risk of making a hospital contact is 12% lower in academically selective local education areas. Once controls are added, this falls to an 8% lower risk. This is a minor difference, at best.

Why are these results important?

Well, when picking schools, parents care don’t just care about education outcomes alone. Some might wonder if they choose to send their child to a grammar school, is this likely to impact their mental health?

While the outcomes explored in this blog are clearly at the more severe extreme end the distribution, they point to no evidence of this being the case. It is also consistent with previous research I have conducted using questionnaire measures that are likely better at capturing milder symptoms of psychological distress.

So, while the pros and cons of grammar schools will no doubt continue to be debated, there is growing evidence that attending such a school isn’t independently related to increased risk of mental ill-health.

***********************************

Acknowledgements

The ECHILD project is in partnership with NHS England and the Department for Education (DfE) and we thank the following individuals for their valuable contributions to the project: Jodie Taylor-Brown, Ian Goodwin, Garry Coleman, Richard Caulton, Catherine Day (NHS England), and Gary Connell, Harriet Fearn, Kirsty Knox (DfE). We are also grateful to Bill South and Alan Cotterill from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for providing the Trustworthy Research Environment for ECHILD.

We thank all the children, young people, parents and carers who contributed to the ECHILD project. We also gratefully acknowledge all children and families whose de-identified data form this research database.

This user guide describes the ECHILD database which uses data from the DfE, NHS England and ONS. The DfE, NHS England and ONS do not accept responsibility for any inferences or conclusions derived by the authors.

This research benefits from and contributes to research conducted by the NIHR Children and Families Policy Research Unit but was not commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

***********************************

[1]: They are really odds ratios. But, given that our outcome measure (hospital contact) is rare, the odds ratio gives a close approximation to the risk ratio.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Surely this question misses part of the picture. Can we add “is attending a school that is a next to a grammar school bad for your mental health?” What is the effect of not being selected to attend a grammar school?

I think this is an important question, but it feels as though hospital contact is an extremely high bar. Interaction with CAMHS or other services is far more likely, and we all know the delays associated with that. There must be better ways to measure wellbeing?

Aren’t students from more advantaged backgrounds more likely to use private health routes than less advantaged students and is that private intake data captured in your measure – or only use of public health services? If the private health data is lacking (which I expect may be the case) that would explain the slightly non-intuitive finding that grammar schools are less likely to affect wellbeing than state schooling… We should also say that there has been a large increase in private health insurance/service usage in recent years due to the real and perceived decline in NHS.