While not attending – or being excluded from – school is a problem for any pupil, it may be particularly concerning amongst young people from disadvantaged backgrounds who were excelling when they left primary school. These young people – despite being raised in challenging circumstances – developed a firm foundation from which one would hope they would flourish. The last thing they – and society – needs is for such potential to go to waste.

This blog continues our research into high-achieving children from disadvantaged backgrounds, focusing on school absences, exclusions and cautions/sentences from the police. The full results are available in this paper.

This is the fourth paper from our Nuffield Foundation project exploring outcomes of high achieving children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. We’ve already blogged about the mental health and a range of other outcomes for this group.

Absences, exclusions and crime

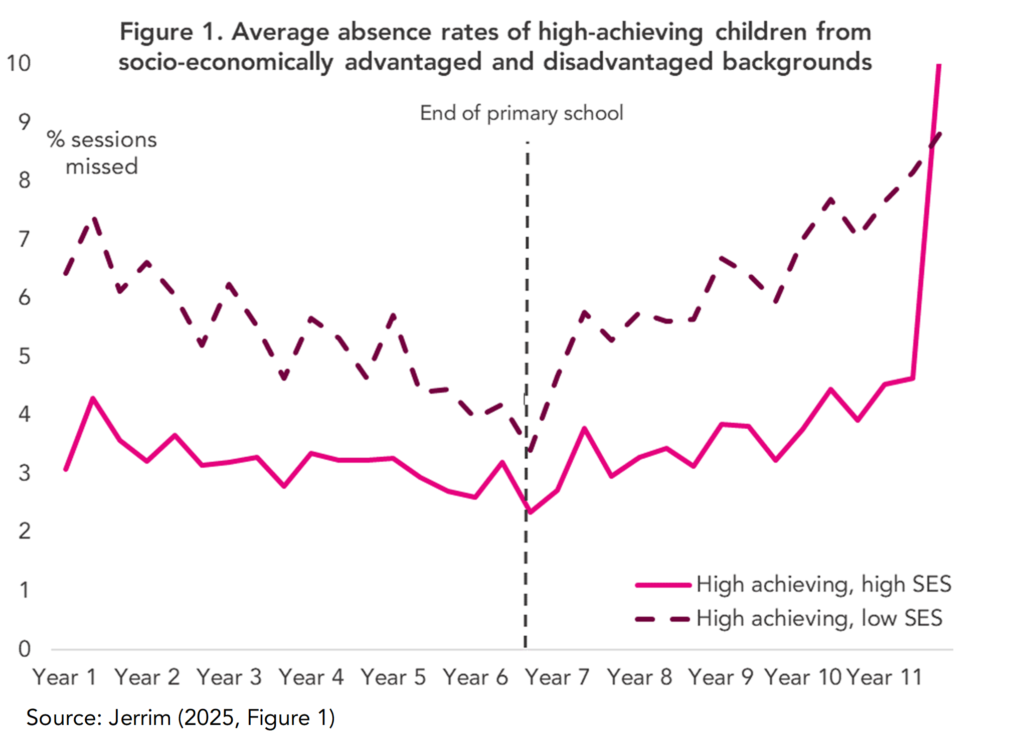

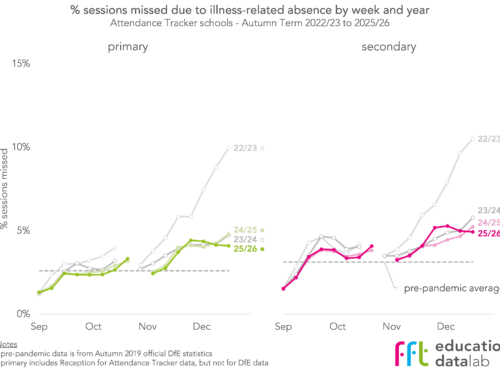

Figure 1 illustrates how school absence rates for high-achieving pupils (top 25% of Key Stage 2 scores) changes by school year group for pupils from socio-economically advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds.

High-achieving disadvantaged pupils consistently have higher absence rates than their equally able but more socio-economically advantaged peers. Towards the end of primary school, this difference is relatively small – between 1 and 1.5 percentage points. Yet this gap grows during secondary school, reaching around three-percentage points by year 9.

This is consistent with our prior research, which has found Key Stage 3 to be a critical period when high-achieving disadvantaged pupils become increasingly disengaged with school. It is also when overall absence rates start to rise including – as Figure 1 illustrates – amongst high-achieving pupils.

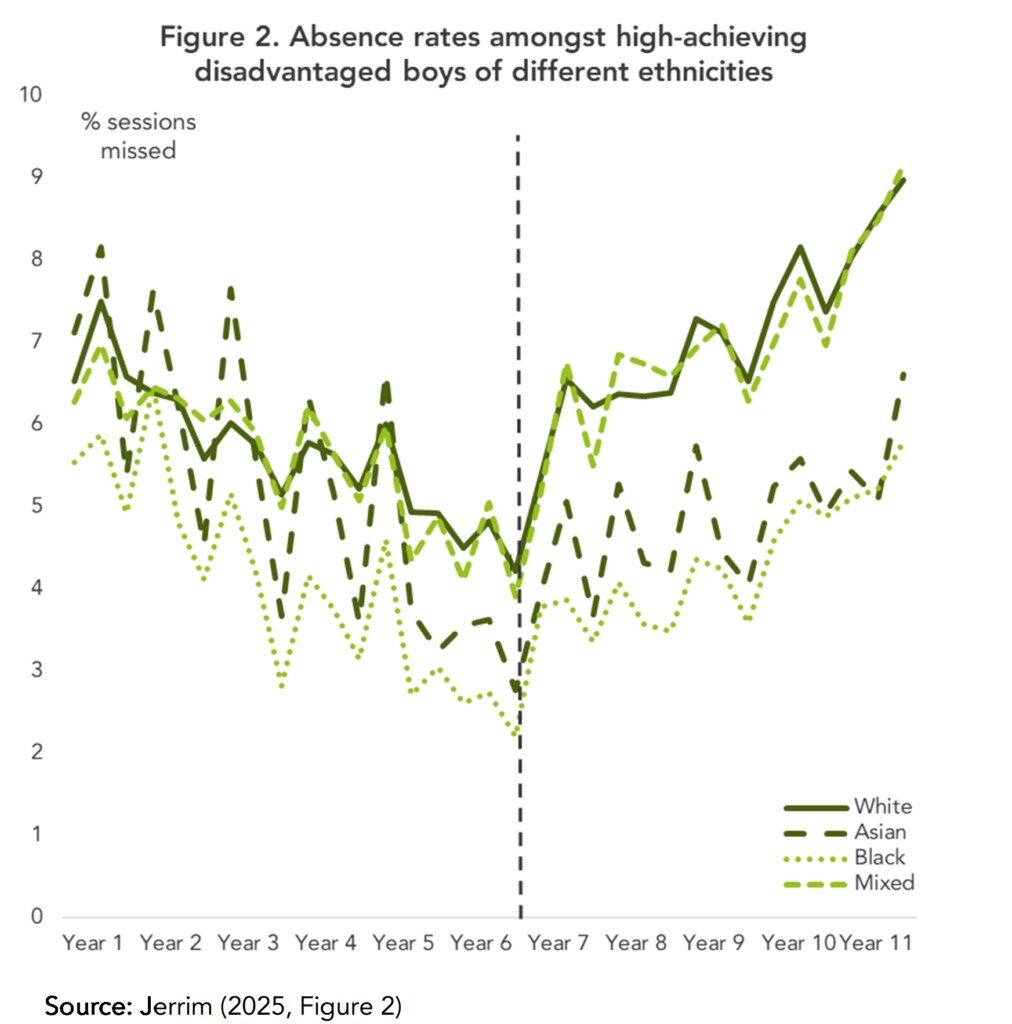

There are however some important differences between high-achieving disadvantaged children of different ethnicities, as illustrated in Figure 2. While there is some increase in absence rates during secondary school amongst each ethnic group, it is particularly pronounced amongst boys from White and Mixed ethnic backgrounds. For high-achieving disadvantaged Black and Asian young people, the increase in the secondary school absence rate is notably smaller.

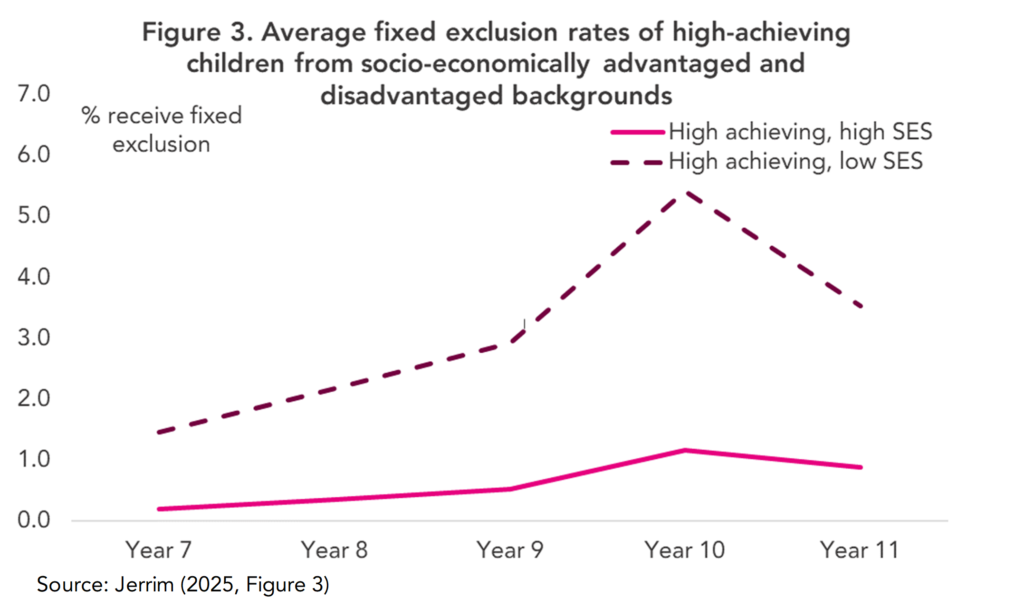

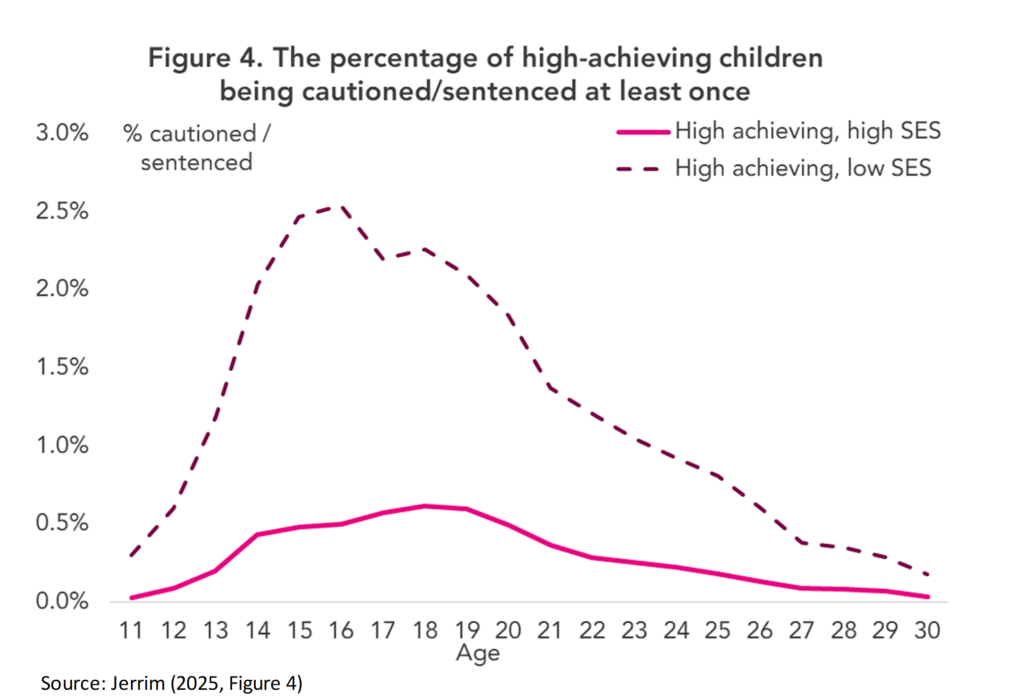

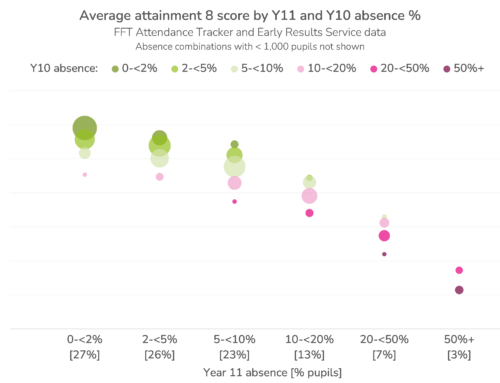

Within the paper, we also consider exclusions from school and police cautions/sentences. Figures 3 and 4 summarise these results. For both outcomes, figures stay very low for high-achieving pupils from the most advantaged socio-economic backgrounds. But for high-achieving disadvantaged children, exclusions and police cautions during secondary school sharply increase, particularly between Years 9 and 10.

Within the paper, we note how important differences again emerge across genders and ethnicities. The sharp increase in school exclusions and police cautions is particularly pronounced amongst high achieving, disadvantaged boys from Black and Mixed ethnic backgrounds.

Implications

What these – and other emerging findings – point towards is Key Stage 3 being a particularly important period for high-achieving children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Previous research has shown this is when this group starts to disengage at school, with the above illustrating this is also when their absence rate starts to increase. Yet – worryingly – this also seems to be when much more problematic issues start to emerge. Being excluded from school and getting into trouble with the police can have serious negative consequences on later outcomes in life.

Given the size of this group – around 3% of the pupil population – it may be possible for schools and policymakers to give high-achieving pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds more focused attention.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

If your first graph is anything to go by, second school is (for all pupils) a far less appealing experience than primary. Which suggests wider, and broader, questions need to be posed about the logics of secondary education, probably in relation to pedagogies, curriculum, high stakes testing and social support.

In the school with the lowest socio-economic background intake (ie a very high proportion of white working-class boys in northern towns), very bright kids end up in top sets for maths with children who are targeting a grade 4. The teacher has to teach to the middle. The lower attaining kids kick off and the higher attaining kids get very bored and join them (many don’t want to be extremely different).

It doesn’t help that the parents have low expectations.