This project has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit nuffieldfoundation.org

For the past couple of years we’ve been working with colleagues at the University of Bath and the Edge Foundation on a mixed methods study evaluating the design, implementation and impact of the raising of the participation age (RPA) in England.

This raised the age at which young people were meant to remain in learning (not confined to school-based learning) to the end of the academic year in which they turn 17 from 2013 and to the time of their 18th birthday from 2015.

It was intended to (a) improve education and skill levels among young people, and (b) help reduce inequality of opportunity[1].[1]

Today, over ten years later, we are publishing our main report.

In this blogpost, we focus on the quantitative side of the project.

Data

We used iteration 2 of the Longitudinal Education Outcomes (LEO) database.

This links school information for all state-educated students in England from the National Pupil Database (NPD) to further education enrolment and attainment from the Individualised Learner Record (ILR), higher education information from the Higher Education Statistics Agency student record (HESA) and other post-16 destinations from the National Client Caseload Information System (NCCIS). This is then linked to administrative data on earnings from HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) and benefit receipt from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

We study 11 cohorts of young people, those who completed Key Stage 4 between 2007 and 2017.

We use a series of linear regression models that aim to isolate the effect of the policy by comparing ‘like-with-like’ students in the cohorts pre- and post-RPA.

We study a range of outcomes, covering:

- Participation in education and training (including apprenticeships)

-

- an indicator for sustained participation in education or training (ET) throughout the first academic year post-16 (Year 12). This is defined as a young person being observed in some form of education or training participation in the October of the academic year and still participating in the January and May of that academic year, i.e. they begin participating and do not drop out during the year.

- an indicator for sustained participation in ET throughout the second academic year post-16 (Year 13)

- for each year: indicators for being in different aspects of ET throughout the year, i.e. being in school, being in further education (FE); an indicator for being in employment; and an indicator for not being in education, employment or training throughout the year

- for each year: an indicator for dropping out after initially making a positive transition to continued education, training or employment at the start of the academic year; an indicator for dropping out specifically from a course started in further education.

In the full report we also study a range of other outcomes related to qualifications achieved and early (up to age 20) labour market outcomes.

Control variables included students’ demographic characteristics (such as gender and ethnicity) and family background, school absence rate, exclusion record (both suspensions and permanent exclusions) and prior educational attainment.

The models also allow for existing trends in participation and outcomes over time, with the assumption being that, having taken account of these trends, we should be able to isolate the distinct effects of the policy on the affected cohorts. The effects of the staged implementation of the policy – with one cohort only having to stay in learning until 17 and subsequent cohorts having to remain until 18 – were built into the model[2].

No other education policies affecting participation were simultaneously enacted with RPA to 17, though the requirement to continue with English and maths if Level 2 had not been achieved by age 16 was first introduced in the same year as the RPA to 18[3], and this cohort and all subsequent cohorts were also affected by a reduction in vocational courses available in FE colleges and schools following the Wolf Review of vocational education for 14-19-year-olds in England. As such, we have to be somewhat cautious in interpreting the effects of RPA to 18 on participation and qualification outcomes.

Results

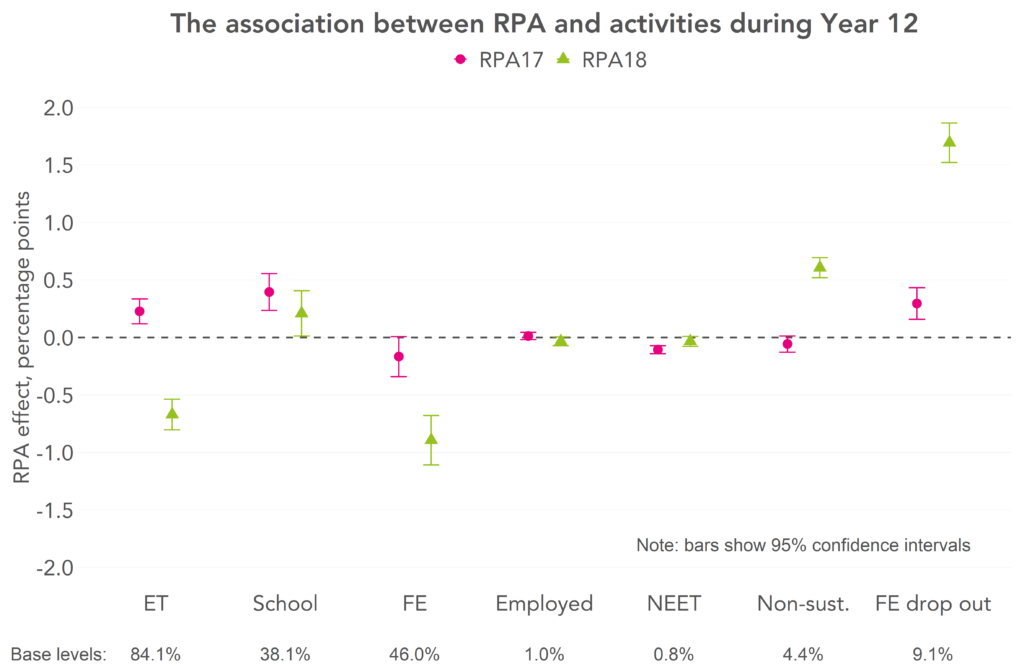

In the chart below we show the changes in various participation outcomes in Year 12 associated with the raising of the participation age firstly to 17 and then up to 18. Each pair of markers represents a different outcome (measured by a different regression model).

The estimated effects capture the additional impacts associated with the introduction of the RPA, compared with the levels of participation for cohorts completing secondary school before RPA. The pink circles show the effect on the cohort impacted by the initial increase in participation age to 17, and the green triangles show the effect on cohorts affected by the full implementation of the policy raising the participation age to 18. The base levels of these variables in the year prior to RPA implementation are shown below each outcome to give a sense of what these changes are relative to.

The first two markers show the association between RPA and overall participation in education or training. When the participation age was initially raised to 17, participation increased by 0.2 percentage points (pp), rising from 84.1% immediately prior to the policy’s implementation.

This is driven by the increase of just under 0.4pp in sustained participation in school from a starting point of 38.1% of young people participating prior to RPA.

There is a small and non-statistically significant decrease in sustained further education (FE) participation. The net effect of these changes is the small increase in sustained education and training participation in Year 12.

Employment in Year 12 is unaffected by the RPA to 17, but the proportion of the cohort who are NEET throughout Year 12 falls slightly. The proportion who begin participating in October but then drop out before the end of the academic year, i.e. non-sustained activity, does not change significantly.

Looking at the green triangles, which show the effect of RPA among the cohorts required to remain in participation until age 18, we now see that overall sustained participation has fallen compared to the cohorts before RPA. While there is an increase in sustained participation in school, this is offset by a larger reduction in the proportion in FE throughout Year 12.

The proportion of the cohort who are NEET is unchanged, but we see a large increase in the proportion of the cohort who make a successful transition to continued education (or employment) but dropout before the end of the year. This was 4.4% of the cohort prior to RPA but increases by 0.6pp with the full RPA to 18.

Looking into this, we can see that RPA to 18 is associated with a 1.7pp increase in the proportion of those who start a course in FE dropping out. This is a non-trivial effect compared to the 9.1% of FE starters who dropped out before the policy was introduced.

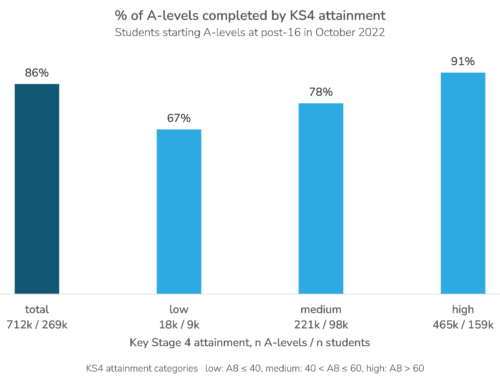

In our report we also look at further outcomes and investigate how outcomes vary among different groups of students. We find (perhaps unsurprisingly) that the effects of the policy are greater for lower attainers at Key Stage 4.

Summing up

We find there was a limited impact of the policy on overall participation in education or training during the first two years post-16.

We firstly see an initial increase in sustained participation age to 17, driven by more young people remaining in school, without a drop in FE participation.

However, we show in the full report that the implementation to 18 saw a fall in overall participation, and a shift of young people from FE to school.

In this article we have only scratched the surface of the report. Colleagues also undertook qualitative studies with national policy architects and key stakeholders (including young people) in six case study areas across England to unpack the story behind the numbers.

This at times presents a bleak picture but we do finish with a cautious note of optimism. We see the RPA policy as having untapped potential to expand learning opportunities for young people, and with that in mind, offer a series of recommendations to find ways of offering earlier intervention during the post-16 phase, in order to reduce the large number of young people with lower Key Stage 4 attainment who drop out, may go unnoticed and then surface to enter the welfare system when they reach the age of 18.

- Department for Education and Skills (2007). Raising Expectations: staying in education and training post-16. Norwich: Cm7065, March.

- See the appendix of our main report

- The ‘conditions of funding’ reform was introduced from August 2014, requiring that education providers ensure that students without a grade C or above (level 4 or above) at GCSE English and maths are required to continue studying them as part of their course until this level or equivalent is achieved

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment