In the first part of this post, we saw that both disadvantage and low early literacy skills were associated with worse longer-term outcomes. In this part, we investigate how outcomes vary by the combination of literacy skills and disadvantage.

The combination of early literacy skills and disadvantage

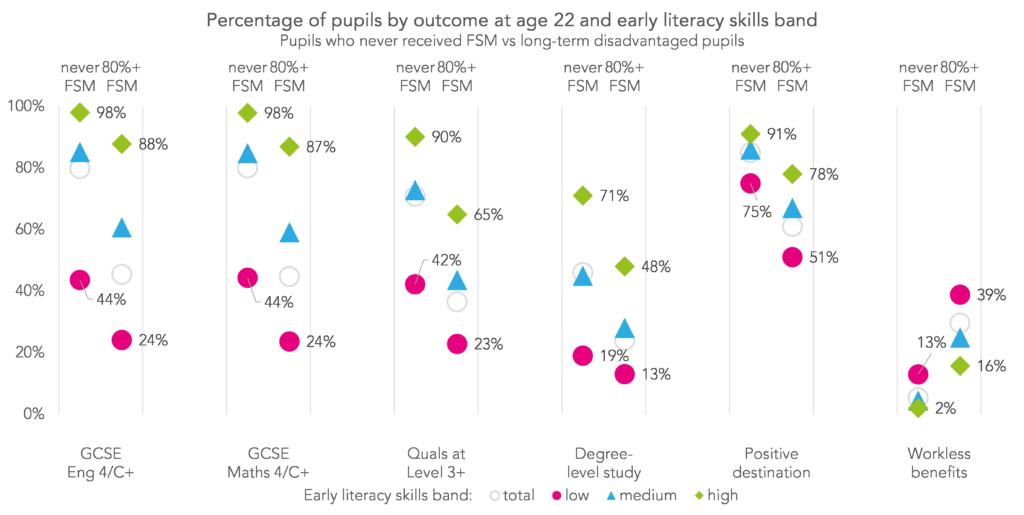

Below we plot the same outcomes we saw in the previous post, again split by early literacy band, but we show results for those who were never eligible for FSM on the left-hand side of each bar, and those who were long-term disadvantaged on the right-hand side.

Although we see that long-term disadvantaged pupils tended to have worse outcomes than the never disadvantaged, the relationship with early literacy skills is still there.

There are some interesting results here. For those with the highest literacy skills, there’s a difference of 12-13pp in GCSE outcomes, but 23-25pp in the proportion going on to obtain L3 qualifications or study for a degree.

And in the final two outcomes – the proportion observed in a positive destination or receiving workless benefits – there’s a bigger difference in outcomes between those with the highest and lowest literacy scores for the most disadvantaged than the least. For example, among never disadvantaged individuals, there’s a difference of 16pp between those with the highest and lowest literacy skills observed in a positive destination, while for the long-term disadvantaged it’s 27pp.

Finally, receiving workless benefits is unique in that it’s the only outcome we’ve studied where never disadvantaged pupils with low literacy skills have more positive outcomes than long-term disadvantaged pupils with high literacy skills (13% of the former vs 16% of the latter).

What about other pupil characteristics?

We could stop here. We’ve shown that pupils with low early literacy skills tend to have worse longer-term outcomes, and that this relationship remains when we take disadvantage into account. But there could be other factors at play. For example, the fact that pupils with low literacy scores were more likely to be male than those with high scores. Perhaps the relationship we see between literacy skills and outcomes is actually a relationship between gender and outcomes.

To see how much of the relationship between early literacy skills, disadvantage, and outcomes can be attributed to other pupil characteristics, we’ll construct a logistic regression model for each outcome. In our model, in addition to early literacy skills and disadvantage[1], we include:

- school region

- gender

- ethnicity

- month of birth

- first census year observed

Once we’ve fitted our models, we’ll be left with the relationship between early literacy, disadvantage, and outcomes which acts independently of other pupil characteristics. (Another way to think of this is as the difference in outcomes between pupils with exactly the same characteristics, e.g. two white British boys from London born in September, whose early literacy scores (and/or disadvantage) are different.)

The adjusted impact of literacy skills

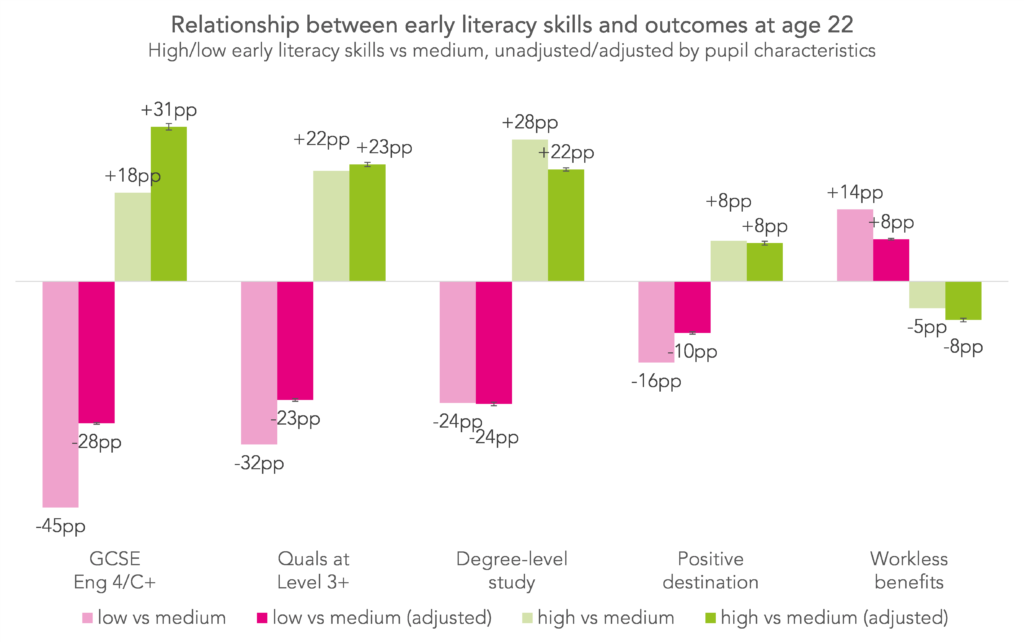

Let’s look again at the relationship between early literacy skills and outcomes. We’ll show the difference between those with low early literacy skills and those with medium, and between those with high early literacy skills and medium. We’ll show the difference adjusted by pupil characteristics (including disadvantage), and the unadjusted difference alongside, for comparison.

The first thing to notice is that although most of the differences have decreased in size, none of them have disappeared altogether. So we can say that there is a relationship between early literacy skills and longer-term outcomes that isn’t explainable by differences in the other pupil characteristics in our model.

The difference for the positive destination and workless benefits measures remains the smallest. This implies that early literacy skills have a weaker relationship with these outcomes than the others. For example, having high literacy skills rather than medium was associated with an 8pp increase in the chances of going on to a positive destination, but a 31pp increase in the chances of achieving at least a C in GCSE English.

The second thing is that, in the unadjusted case, the “cost” associated with having low early literacy skills was generally greater than the “bonus” associated with high skills. But in the adjusted case, they’re roughly the same size.

Could better early literacy skills mitigate the impact of disadvantage?

Returning to the question we asked in Part 1: how far can early literacy skills mitigate the effects of long-term disadvantage?

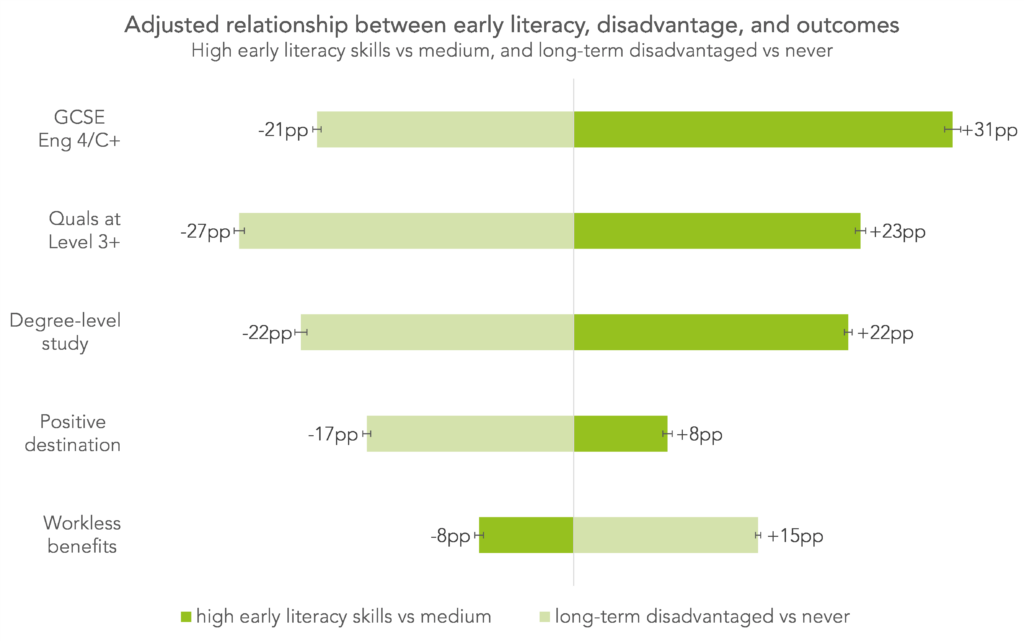

We’ll answer this question by showing the adjusted difference in outcomes between those with high early literacy skills and those with medium, alongside the adjusted difference between long-term disadvantaged and never disadvantaged pupils.

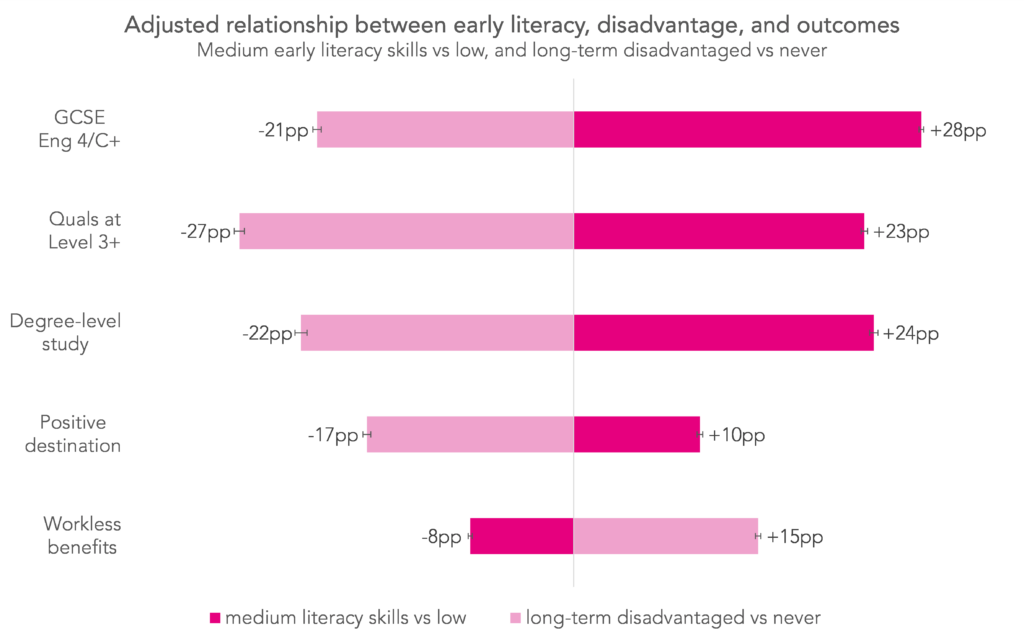

In the three education outcomes – GCSE English, Level 3 qualifications, and degree-level study – the improvement in outcomes associated with having high early literacy skills rather than medium is roughly the same or greater than the worsening associated with being long-term disadvantaged rather than never. This means that long-term disadvantaged pupils with high early literacy skills had the same or better outcomes than never disadvantaged pupils with medium early literacy skills.

In the two broader outcomes – being in a positive destination and receiving workless benefits – the opposite is true, meaning that disadvantaged pupils with high early literacy skills had worse outcomes than never disadvantaged pupils with medium early literacy skills.

The picture is similar when we compare medium literacy skills with low.

Limitations and further work

We’ve shown that improved early literacy skills are associated with better longer-term outcomes, and the magnitude of this improvement is similar in magnitude to the negative association with long-term disadvantage (for education outcomes, at least).

We’ve not shown that improvements in early literacy skills cause improvements in outcomes. For that, we’d need to be sure there’s nothing unobserved which could have impacted both literacy skills and outcomes.

And we’ve not tried to separate early literacy skills into a component which is specifically related to literacy, and a component which is related to academic achievement more broadly.

[1] Early literacy and disadvantage are both converted to discrete variables to match the rest of this work. Early literacy skills according to results in KS1 reading and writing tests: high/medium/low/none. Disadvantage according to the percentage of terms a pupil is eligible for FSM: 0% of terms/<25% /25-50%/50-80%/80%+

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment