Back in 2011 I wrote a paper about academic progress made by “bright” children from poor backgrounds.

It caused rather a stir at the time. This is because it was previously believed that – in the words of Michael Gove – “rich, thick kids do better than poor, clever children before they go to school”. My paper showed this was unlikely to be the case, and was probably being driven by a statistical artifact known as regression to the mean.

One limitation is that – at the time – we could only track the outcomes of those smart, poor kids through to age 7. Now, however, we can observe their progress through to age 17.

In a new academic working paper published today – funded by the Nuffield Foundation – my co-author Maria Palma Carvajal and I have updated the evidence about this group. In this, we explore a whole range of outcomes for this group from age 7 through to age 17.

Big differences in GCSE grades

First, some caveats.

We use data from the Millenium Cohort Study, and sample sizes are relatively small – our dataset only includes just under 400 “bright” children from poor backgrounds.

The tests we use to identify “bright” children also have limitations, being based on assessments taken at ages 3 and 5. We discuss this issue of measurement error at length in our paper and how we attempt to adjust for it in our analysis.

The results are, nevertheless, interesting.

Our central estimates suggest that – during primary school – “bright” 5-year-olds from poor backgrounds largely manage to keep pace academically with their equally bright but rich peers.

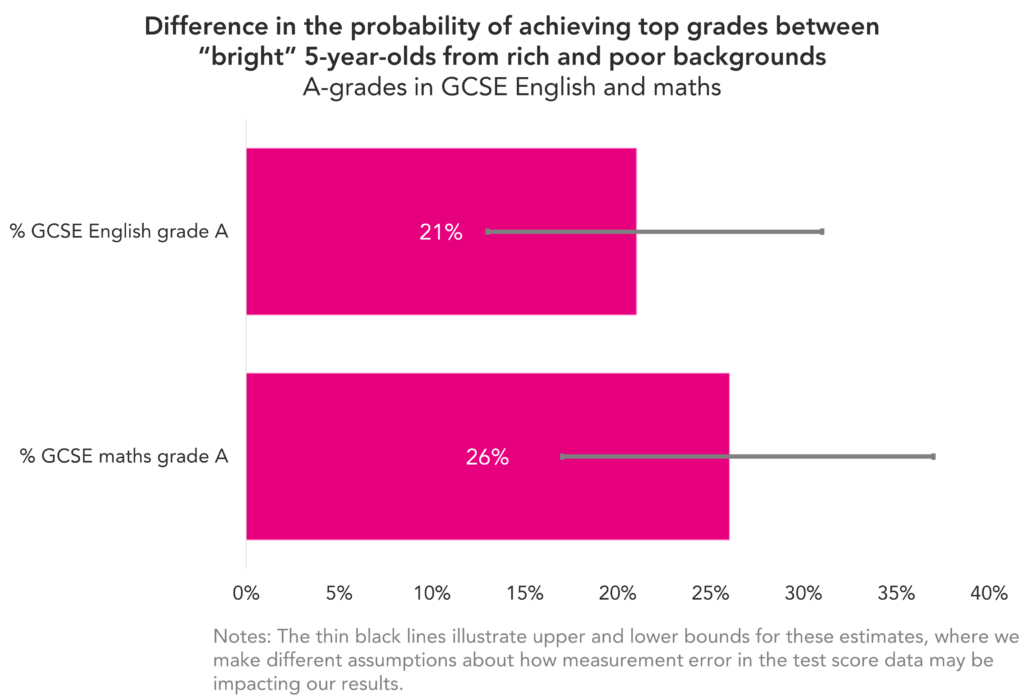

But the same does not hold true with respect to achievement at the end of secondary school. The chart below provides best estimates of the difference in obtaining the equivalent of a GCSE A-grade in English and mathematics amongst “bright” 5-year-olds from rich and poor backgrounds (some of the MCS cohort would have taken their GCSEs prior to the alphabetic to numeric grade reforms).

We find that bright-but-poor 5-year-olds are around 26 percentage points less likely to achieve an A-grade in GCSE mathematics than bright 5-year-olds from the richest backgrounds. The analogous difference for GCSE English is around 21 percentage points.

What may be driving this result?

While it’s hard to say for sure what is driving these differences, the data does provide some clues.

For instance, Key Stage 3 – between the ages of 11 and 14 – seems to be a critical period. This is when we see sizeable differences in the cognitive skills of early high achievers from rich and poor backgrounds emerge, which is consistent with previous research.

This also coincides with when these groups seem to really start to differ in their engagement in school. For instance, at age 14, children from low-income backgrounds with strong early test scores are 11 percentage points less likely to say it is important to work hard as their high-income peers.

They are also much more likely to be hanging out with a troublesome peer group, and 12 percentage points more likely to report having been in trouble with the police.

Why these results are interesting – and what we don’t currently know

Bright children from low-income backgrounds are an important group for promoting social mobility. We know the early years are important – and they have managed to come through those with the basic skills needed to flourish at school.

The fact that they are much less likely to go on and achieve top grades at the end of secondary school is therefore telling.

Yet there remains much we don’t know about the later life outcomes of this group. When – and why – do they start to disengage with school? How does this go on to impact broader aspects of their life, such as their wellbeing and getting in trouble with the law?

And how does this intersect with other characteristics such as ethnicity and gender? Are there, for instance, particular issues facing bright-but-disadvantaged White boys?

I will be exploring such issues as my project with the Nuffield Foundation progresses. This will hopefully provide the most detailed evidence on the outcomes of initially high-achieving young people from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds to date.

Fascinating, but slightly shocking, post. The suggestion that the issue does not seem appear until moving into secondary school certainly need looking at.

One suggestion could be the level of ‘other support’ that goes into normal primary provision for those identified as disadvantaged. At my school we have all staff fully trained on Attachment and Trauma – informed practices, Learning Mentors that are accessible when needed, etc – but we also have that ‘family feeling’ that secondary schools would struggle to replicate due to size, and this allows support to be put in quickly. Perhaps part of the issue, isn’t the academic support, but SEMH/ pastoral.

The curriculum also becomes more of a challenge in secondary school, ‘natural ability’ starts to run out, is this where the financial advantages homes, and they are varied, of the ‘rich’ can support more?

As someone involved in education in Kent, I’d love to know what the grammar effect is on these pupils, although I realise your sample is probably too small to tell. But do “bright” poor kids pass the Kent test? If so, what then? Could there be some sort of middle-class bias within the grammar system? Or if they don’t pass, why not? and what then? I’d like to know the impact of tutoring – are wealthier children offsetting a poor educational offer with tutoring? particularly for the Kent test and in maths?