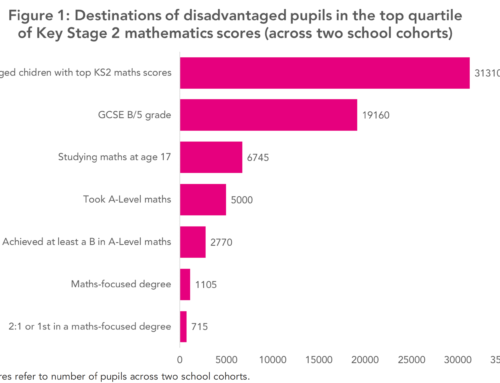

Policymakers and educators often search for the clearest routes into elite professions. One promising — and under-explored — route is supporting children from low-income families who already show strong academic potential at the end of primary school.

These youngsters have beaten early odds: they’ve built skills and habits that make further progress more likely than for peers who fall behind. But early promise alone is not enough. To reach high-status careers these pupils must convert early attainment into strong GCSEs and A-levels, secure places at selective universities, and often be able to move away from home to access internships and networks.

Sign up to our newsletter

If you enjoy our content, why not sign up now to get notified when we publish a new post, or to receive our half termly newsletter?

Yet surprisingly little research follows their full journey from primary attainment to undergraduate and postgraduate outcomes. We explore this issue in a new academic working paper published today. Using large scale administrative data, we explore the educational outcomes of the highest-achieving pupils from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, comparing their fate to their more socio-economically advantaged peers.

This is part of our ongoing project – funded by the Nuffield Foundation – into the outcomes of initially high-achieving pupils from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds.

Findings

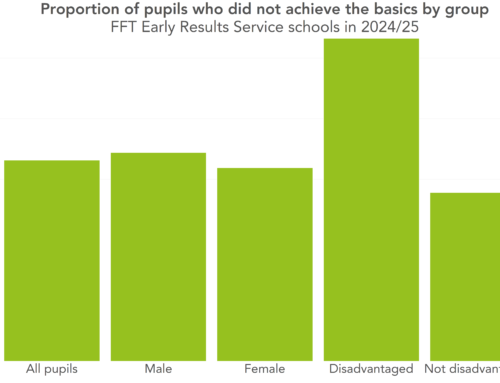

First, school performance clearly diverges across high-achieving pupils from different socio-economic backgrounds. High-SES pupils who were equally able at age 11 go on to outperform their disadvantaged peers by around 0.3 standard deviations in their GCSEs.

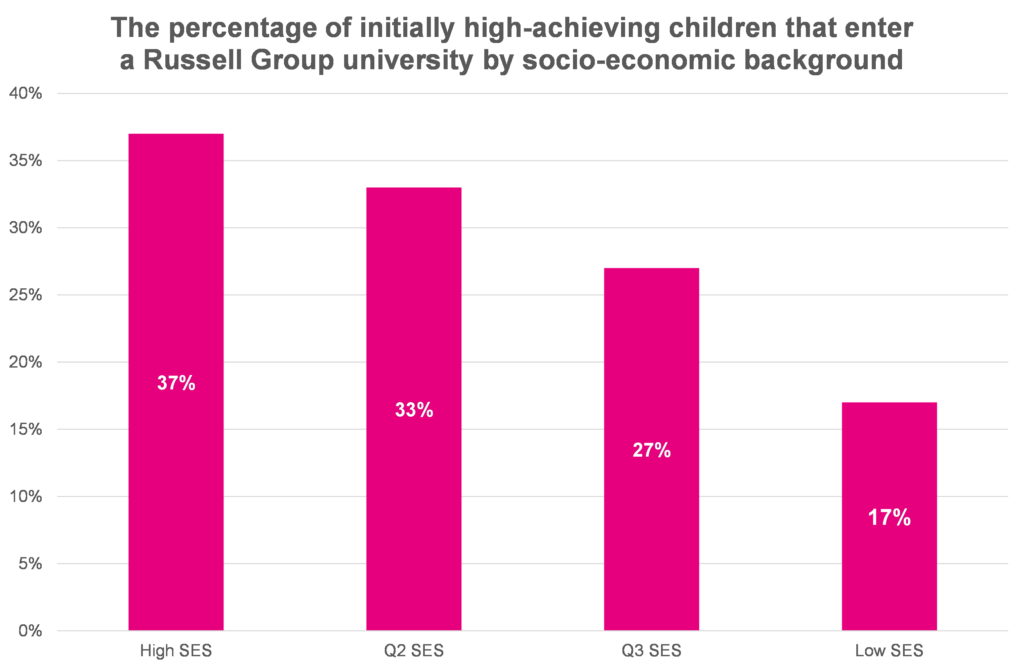

Second, these differences in grades translate into big differences in university access. Roughly 37% of high-SES top-quartile pupils entered a Russell Group university by age 21, compared with about 17% of low-SES peers. For entry to any university the contrast is also large: around 75% of advantaged high-achievers went to university by 21 versus 57% of disadvantaged high-achievers in the same cohort. See the chart below.

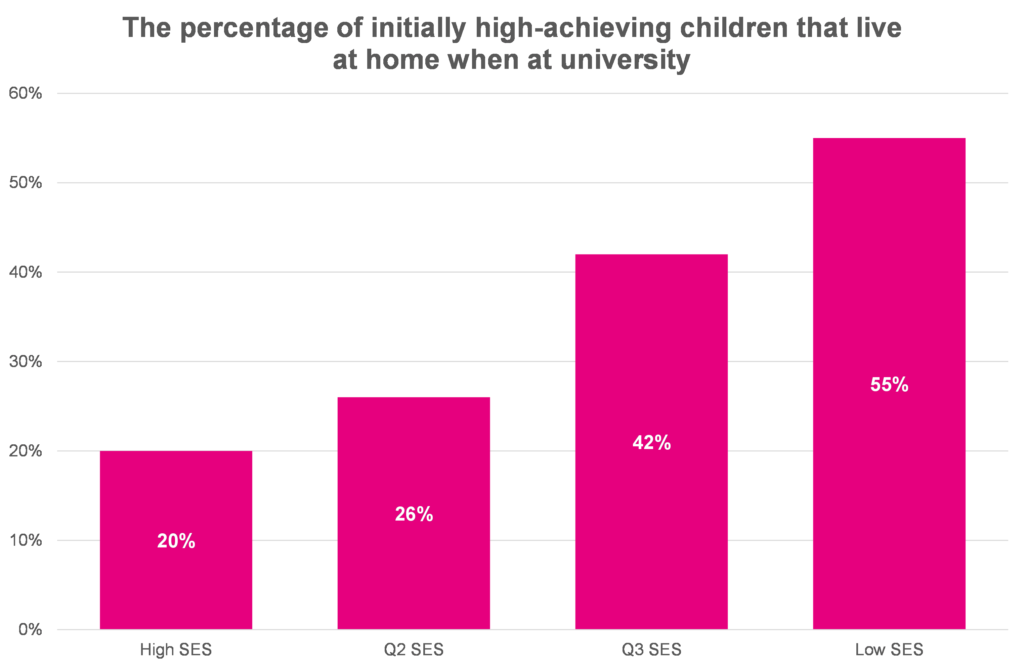

Third, university experience differs too. Roughly half of high-achieving pupils from poor backgrounds live at home while studying at university. This compares to only around one-in-five of pupils from the most advantaged backgrounds that achieved similarly high SATs scores at age 11. See the chart below: even after accounting for grades and the university attended, disadvantaged students are substantially more likely to remain at home — a decision that affects social networks and the time available for on-campus activities.

Fourth, subgroup patterns are important. Disadvantaged Asian pupils frequently sustain stronger academic progress than disadvantaged White pupils and are often more likely to enter selective universities once their exam results are accounted for. For instance, the odds of initially high-achieving White pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds entering a Russell Group university are around 40 to 50% lower than their Black and Asian peers. Indeed, access to university seems to be a particularly big issue facing initially high-achieving, disadvantaged White girls.

Implications

These findings point towards more needing to be done — and sooner — to help disadvantaged children who shine in primary school convert that promise into strong GCSEs, A-levels and selective university entry. This is especially urgent for White pupils, who are the most likely to lose ground during secondary school.

Also, understanding why some talented students are reluctant to leave home remains an under researched area. But if one believes moving away from home is an important part of the university experience, policymakers and institutions should reduce barriers that make high-achieving disadvantaged students more likely to stay put.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment