Update 1pm, 30 May 2018: In response to a comment, which correctly noted that one establishment had been double-counted in this analysis, some figures have been updated. Full details can be found in a comment below.

This is a joint blogpost from FFT Education Datalab and The Difference.

The Difference is a new training programme, creating the next generation of school leaders, upskilled in supporting pupil mental health and reducing exclusion from school. Leaders spend two years teaching in alternative provision while studying a specialist leadership course, focusing on mental health, safeguarding and improving outcomes for vulnerable students. Learn more about The Difference here.

In March we launched an attempt to crowdsource information about the independent alternative provision sector in an effort to plug an information gap.

After a great response – thanks again to all those who contributed their time – we have used the data generated to build a unique picture of the sector.

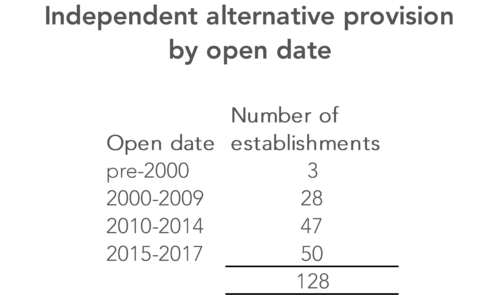

After reviewing the data generated in this crowdsourcing exercise, we think there were 128 registered independent establishments offering alternative provision in England in 2017.[1] (Though see below for discussion of some of the difficulties of categorising establishments.)

We’re making a list of these establishments available here, but we’ve pulled out some headline findings.

1. There are more than 2,500 pupils on-roll in independent alternative provision

A total of 2,748 pupils were recorded as being on-roll at the 112 establishments for which pupil numbers were available.[2] (No pupil figures are available for 16 establishments, as they opened after the January 2017 census date, which is the latest for which data is available.)

Two-thirds of pupils are boys; one-third girls – 1,815 versus 915 (numbers are rounded to the nearest five).

It is worth remembering that, while these are the pupils recorded as being on-roll at the establishments in question, there may be more pupils attending them as off-site alternative provision, without joining the roll of the independent alternative provision.

2. This is a young sector

Nearly two-in-five establishments (50 out of 128) have open dates since 2015 – though some at least may have been operating as unregistered alternative provision before this point.

A full breakdown is shown below.

There has also been a high level of closures, with 12 of these 128 establishments closing during 2017 or 2018.

3. Inspection ratings are worse than for state alternative provision

Of the 116 independent alternative providers that remain open, 109 are inspected by Ofsted, with the other seven inspected by the Independent Schools Inspectorate (ISI).[3]

Of those that have had an Ofsted inspection, the sector is less likely to have a positive inspection rating than is the case for mainstream schools or state alternative provision.

A total of 72% of independent alternative providers have a good or better inspection rating, using the latest data published by Ofsted, which gives the picture as at 31 March 2018.

This compares to 89% of state alternative provision, and 79% of mainstream secondary schools, [PDF] with a good or better inspection rating, as at 31 August 2017.

A full breakdown of the figures for independent alternative provision is given in the table below.

Quite a large number of establishments that fall under Ofsted’s remit – 13 – have not yet been inspected.

Unlike Ofsted inspections, ISI inspections do not result in an overall inspection rating. But of the seven establishments inspected by ISI, only two have had a full inspection to date, both of which were positive.

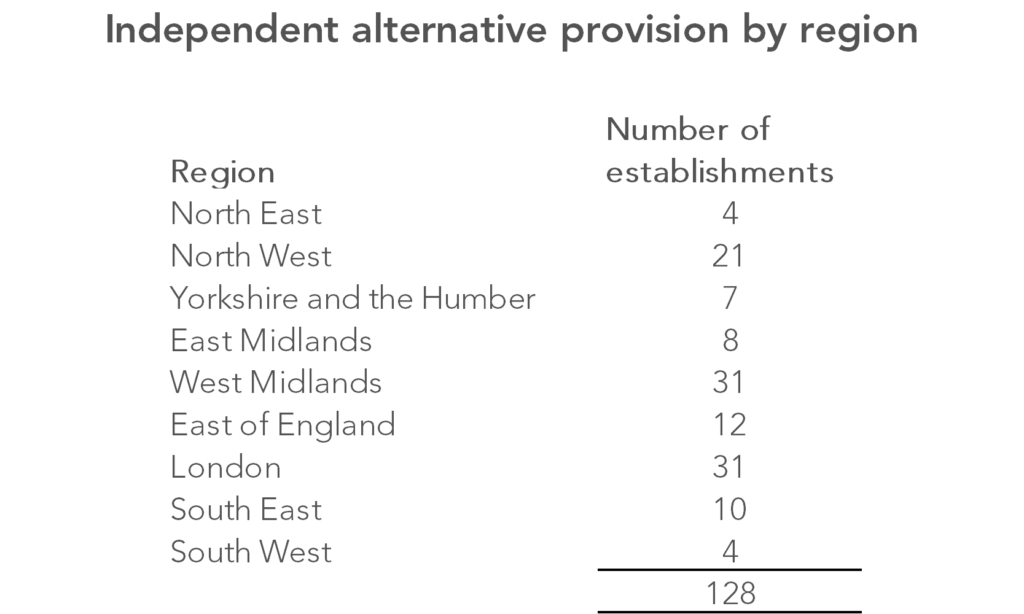

4. There is a surprising geographical spread

The amount of independent alternative provision varies considerably around the country.

There were 16 establishments in Birmingham. While a large local authority, that dwarfs the number seen in the local authority with the next highest number (Manchester, with six establishments).

Greenwich, Stoke-on-Trent and Lancashire all had five establishments – which might seem surprisingly high in the first two cases. Many local authorities have no independent alternative providers, while others generally have one, or two, establishments.

This is likely to reflect a number of different factors, including differences in the use of alternative provision by mainstream schools and the availability of state alternative provision.

5. The boundary between independent alternative provision and the independent special school sector appears porous

The Department for Education records independent special schools as a distinct category of establishment, so our crowdsourcing exercise attempted to focus strictly on those independent establishments not recorded as such.

In a number of cases, however, the reasons why an establishment is not recorded as an independent special school seem somewhat hazy. There also seems to be some switching between the two DfE categories (general independent, and independent special) over time.

For the purposes of this exercise, while recognising that this boundary appears somewhat flexible, in reviewing the data generated in the crowdsourcing exercise these borderline cases have generally been counted as independent alternative provision. This is because the DfE separately records some establishments as independent special schools, so at some point at least a decision has been made not to classify these individual establishments as such.

(One quick note: no analysis of attainment or pupil progress has been attempted due to the scarcity of data available, though where it exists this data from the 2017 school league tables has been tacked on to the data we are making available).

Overall, then, this exercise has helped build a picture of the independent alternative provision sector that we previously didn’t have. But one awkward fact remains.

Unregistered provision

By necessity, the starting point for this crowdsourcing exercise consisted of establishments registered with the DfE.

And establishments only need to register with the DfE as a school if they meet certain criteria:

An AP provider should be registered as an independent school if it meets the criteria for registration (that it provides full-time education to five or more full-time pupils of compulsory school age, or one such pupil who is looked-after or has a statement of SEN).

Department for Education statutory guidance for alternative provision, 2016[4][5] [PDF]

A concern that has been expressed by a range of parties, then, is that there are an unknown number of establishments operating below these thresholds – only providing part-time education, or providing full-time education for fewer than five pupils, say.

And these establishments we genuinely know nothing about.

That leads us to the first of two appeals that we would make to those in government.

Firstly, we have concerns over whether there is sufficient regulation and oversight of unregistered alternative provision.

We will avoid here the question of exactly how much regulation might be appropriate, but as a minimum we think that if a school or alternative provider is making use of (currently) unregistered alternative provision, that provision should in fact be registered with the DfE.

Secondly, as we have stated before, we would make the case for independent alternative provision to be recorded by the DfE as a category of establishment in its own right, distinct from mainstream independent schools.

Until this is done, analysis of the type that we have carried out here is just not possible without people dedicating large amounts of time and energy to looking into individual establishments.

We’re interested to know what others make of the data, and what they can use it for – do leave a comment below letting us know.

Follow The Difference on Twitter, or sign up to their weekly newsletter.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. The starting point for our list was the 2017 Key Stage 4 league tables, though following a helpful comment we expanded this list somewhat to take in other independent establishments open in 2017, to ensure that small providers that had not entered any pupils for KS4 exams in 2017 were captured. Two establishments could not be classified, as no information could be found about them online.

2. In theory there should be no double-counting between one establishment and another, but as far as we’re aware there’s no mechanism through which this could be checked, so some double-counting may occur.

3. Schools that are part of one of the independent school associations are inspected by either ISI or SIS, the School Inspection Service, rather than Ofsted.

4. While not set down in legislation, government guidance states that institutions operating for 18 hours per week or more would generally be considered to be operating full-time.

5. Schools Week has also reported [PDF] that some establishments do not currently need to register as they do not meet the definition of a school, on account of not providing a “suitable education” if their offering is particularly narrow. It’s not clear if any alternative providers fall into this category.

Thanks very much for this The geographic notes seem to corroborate your similarly excellent “pupil moves into the independent sector”. Is it technically possible to expand these posts and add LA PRU/AP data to provide a definitive view of the number of pupil moves into and out of all AP/PRUs no matter the governance of the provisions? At least for all pupils with a KS4 result?

PS

I notice that lines 48 and 49 (Horatio House) differ only in their LA number, are they really two different provisions?

Hi Chris,

Firstly, thanks for the kind comments – glad you’ve found the blogposts useful. Agree that moves to AP overall, regardless of governance, would be worth calculating figures on – more on that soon.

And re: Horatio House, you’re entirely right – this establishment has been double-counted as a result of a change in LAEstab. I’ve checked, and that’s the only establishment affected, but that’s still one more than I’d have liked! Figures in the post have been updated now to reflect this, as too has the data which we’ve made available for download. The impact is as follows (previous figures in brackets):

Total establishments: 128 (129), of which 116 (117) remain open

Total pupil count: 2,748 pupils (2,772) at 112 (113) establishments for which pupil numbers are available. Of which, there were 1,815 (1,835) boys and 915 (920) girls, rounded to the nearest five

Open dates: 50 (51) out of 129 (128) have an open date of 2015 or later

Inspection ratings: 96 (97) out of the 109 (110) establishments inspected by Ofsted have had a full inspection, with 72% (71%) of these receiving a good or outstanding rating

Good evening Philip and Kiran, thank you an excellent article and very timely for some work we have been involved in with current registered and unregistered providers for a LA this year. Our quality assurance outcomes echo areas picked up in your article. If you would find it of value to your study, we would be happy to have a discussion with you.

kind regards,

Julie Chong, Director of Educational Projects

Thanks for the kind comment, Julie – and interesting to hear that themes picked up here chime with what you’ve observed on the ground. Would love to hear more about your work, and in particular what you were able to find out about unregistered provision – will drop you an email. Thanks.