Before the 2017 general election, it seemed like grammar schools were about to make a widespread return to England.

Although this didn’t happen after the Tories lost their parliamentary majority, the new Secretary of State for Education has backed plans to allow existing grammar schools to expand.

This renewed interest in expanding selective education has helped to highlight how around 5% of secondary-age children in England currently attend a grammar school, with around one-in-ten young people in England already effectively living within a selective education area.

Towards the end of primary school many children and their families face a nervous time waiting to find out if they have managed to gain entry into a grammar school.

This raises an important question – what are the factors that make the difference to gaining entry? And to what extent do these factors create a gap in grammar school attendance rates between the rich and poor?

The role of private tuition

In a recent project funded by the Nuffield Foundation, Sam Sims and I have explored this issue. Although the report covers a multitude of issues, today I want to focus on the role of private tuition.

It has long been thought that ‘coaching’ for entrance tests is likely to be important and, despite claims of tests being ‘tutor-proof’, may provide an unfair advantage to children from an affluent background.

Today, I can provide hard evidence that this is the case.

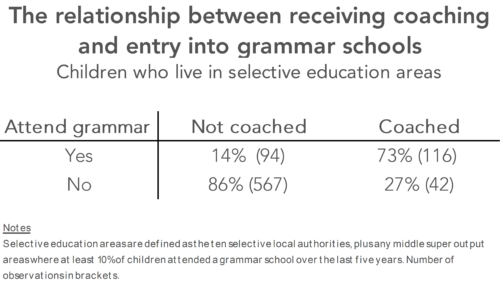

First, consider the table below. It illustrates the probability of getting into a grammar school in England depending on whether tutoring or coaching for the entrance test has been received.

Around 70% of those who received tutoring got into a grammar school, compared to just 14% of those who did not.

This huge impact of tutoring continues to hold even after a wide range of other factors (e.g. prior achievement, school application decisions) have been taken into account. In other words, receiving tuition for the entrance test really does seem to matter.

Second, who receives such tuition?

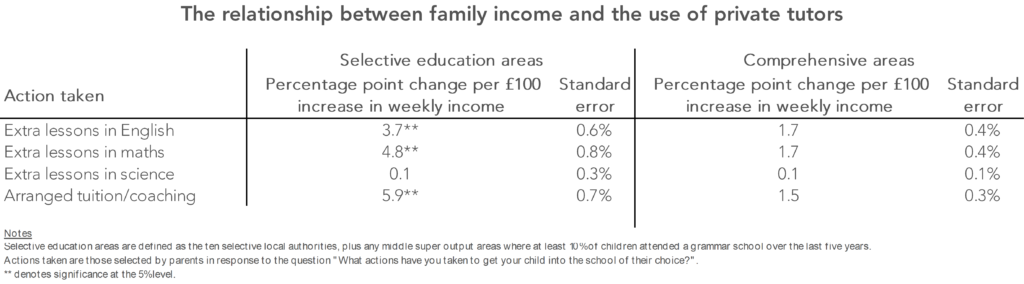

The table below considers the percentage point increase in the use of private tutors for each £100 increase in weekly family income.

Notice how affluent families living in selective education areas in England are much more likely to invest in private tutoring services than lower-income families.

This is particularly true in English and mathematics – subjects covered in grammar school entrance tests – but less so for science – which is not covered in the entrance tests.

There is also less of a social gradient in the use of private tutors at the end of primary school in comprehensive parts of the country.

In other words, private tutoring is disproportionately used by – and benefits – the rich within selective education areas.

In fact, another finding from our research is that families in the top quarter of the income distribution who live in selective education areas in England are around 25 percentage points more likely to pay for ‘coaching’ to get their child into a grammar school than families in the bottom quarter of the income distribution.

Rebalancing the system

Put these two findings together, and it becomes clear that private tutoring is an important driver of inequality in access to grammar schools.

What should be done about this?

One option would be for the government to consider putting an additional tax onto private tutoring services.

With the money raised, a voucher system could be put in place to provide heavily subsidised private tuition for children from low-income backgrounds.

Such a tax would both reduce demand for private tuition amongst high-income families, while simultaneously increasing their use among lower-income groups.

If the government is to expand grammar school places, and is equally serious about promoting social mobility, intervention of some kind will be necessary in order to provide a level playing field.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from Education Datalab? Sign up to our mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive our half-termly newsletter.

It would be interesting to know how many on the non coached in a non grammar school in the study did the “11+” and “failed” as opposed to applied for their nearest school (comp) because it was where they wanted to go / were willing to travel to.

To what extent is coaching influenced by pupil ability in y3 /4 as informed by teachers? are “more able” children coached more than “expected standard” or “below expected standard”. The extent income has on ability in school is identified via pupil premium attempting to reduce the gap.

Is the income reflecting “aspiration” (for some) rather than ability to pay for coaching? (for some)

Much private tutoring is “cash in hand” and hidden – even at the school gates.

Chas: I think what you’re after (“are “more able” children coached more than “expected standard” or “below expected standard””) is here: https://educationdatalab.org.uk/2015/03/the-lucky-children-who-just-get-into-grammar-schools-dont-appear-to-achieve-more-than-their-primary-school-contemporaries-who-just-miss-out/.

It may be that you’ve not included all the data you have, but your statement that “Around 70% of those who received tutoring got into a grammar school, compared to just 14% of those who did not.” does not prove that “private tutoring is an important driver of inequality in access to grammar schools”.

Nowhere do you provide evidence that buying tutoring actually LEADS to an increased chance of a place at a grammar school. The causation could just as easily work in reverse – that those parents who want to send their kids to grammar bother to pay for tutoring. Those who don’t pay for tutoring are most likely to be those who don’t care if their kids go to grammar schools or not, so see no need to waste the money. It doesn’t prove that tutoring actually impacts on children’s chances in the exam; it could just as well be that lots of people buy into the ‘hype’ of tutoring so pay for it if interested in a grammar school place for their child, whether or not it is beneficial. Without comparing figures on those who apply versus those who get in, and how much tutoring they received, the figures given here fail to make the point you are trying to make.

Certainly, professional tutors will seize on your research as ‘proof’ that what they do makes a difference and is worth paying for. But your research also fails to clarify what is meant by ‘coaching’ – do parents doing a few past papers with their child also count? What about comparing parents who tutor more extensively with paying for so-called ‘professional’ tutors instead?

There might well be arguments for familiarising all pupils with past papers in selective areas. I would also be unsurprised if research showed that parental support was actually more effective than paid-for tutors (and free too, thus negating your point about income levels and inequality).

I think equality of opportunity is immensely important. But I am suspicious of research that purports to claim that paid tutoring is crucial, when the data does not actually prove that. This kind of conclusion is often used by those who oppose grammar education to argue that grammar schools discriminate against the poor. But the opposite conclusion could equally be reached, if it turns out that parental tuition is just as or even more effective than paid tuition – it could be that grammar schools could provide an essential opportunity for children from poor-but-bright families to get a top quality, free education. Or it could be that the best way to ensure equality of opportunity is to provide a basic intro to a couple of past papers in primary school, and that that will be sufficient. There is certainly no evidence that years of intense paid-for coaching pays off and the children who suffer from enduring this would benefit from this myth being examined much more critically.

This is a very interesting article. However there will always be an imbalance when we have selective school systems. It’s not just income that is a barrier to children and their opportunities for success but their parents willingness to support them in providing/facilitating those opportunities.

Paying for tutoring is only one way in which some parents support and facilitate their child’s chances of gaining a place at a selective school. It is utterly pointless to examine paid for tutoring in isolation and conclude that paid for tutoring needs to be singled out for punishment. The scandal is not parents who support their chikdren’s education (and tutoring is one of many possible options), but parents who do not.

Having worked in and been on the governing body of a grammar school I often raised the issue of the impact of tutoring. The issue was initially brought to my attention from analysing CAT scores for the new year seven intake. This showed significantly greater ranges of scores then I would’ve expected in a selective grammar school. A significant number of pupils scored less than 100 and were intensively coached. Moving to a fairer entrance exam should be the first step. A CAT test would be a viable option in my opinion.

So your solution is to tax tutoring which means that it will actually become even more expensive and exclude those parents who make economies to afford it

Sounds a lot like the argument that the elite use against grammars which has resulted in the return of elite positions to the rich