The education secretary, Gavin Williamson, announced on Monday that all teachers will be paid at least £30,000 by 2022. For context, the minimum point on the main pay scale is currently £24,373. It’s not often that government announces pay rises like that!

Why the splurge? Putting the politics to one side, one of Damian Hinds’ former special advisors explained that the policy was intended to make starting salaries competitive with other graduate occupations, in order to tackle shortages. The £30k headline is designed to “cut through on campus.”

Is this enough to make teachers’ starting salaries competitive? Of course, we don’t know what graduate salaries will be in 2022, but if we’re willing to project forward from recent Higher Education Leavers Statistics, we can make an educated guess.

The chart below shows the median starting salary of graduates from English universities in eight subjects. Salaries are for the year after graduation, for those in employment.

Despite some wobbles, starting salaries for all eight degree subjects appear to be following a gradual upward trend over the five year period between 2013/14 and 2017/18. The dashed lines project these trends forward over the following five years.

By 2022, all of these degree subjects are likely to have median starting salaries below Williamson’s £30k.

Even maths and computer science graduates – on average – can expect higher first-year pay if they choose to go into teaching, though this is very likely to be reversed in subsequent years of their careers.

It’s also worth saying that a London weighting will be preserved, on top of the £30k figure – so the pay premium for a London teacher when compared to a typical graduate with the same degree subject will be even greater.

These graduate pay projections are subject to considerable uncertainty. But if the UK enters recession in the next couple of years – as some are predicting – then the first-year pay premium for teachers is likely to be higher, not lower, as a result.

The £30k starting salary represents a marked change in the government’s approach to plugging teacher shortages: away from bonuses targeted at shortage subjects, towards blanket pay increases.

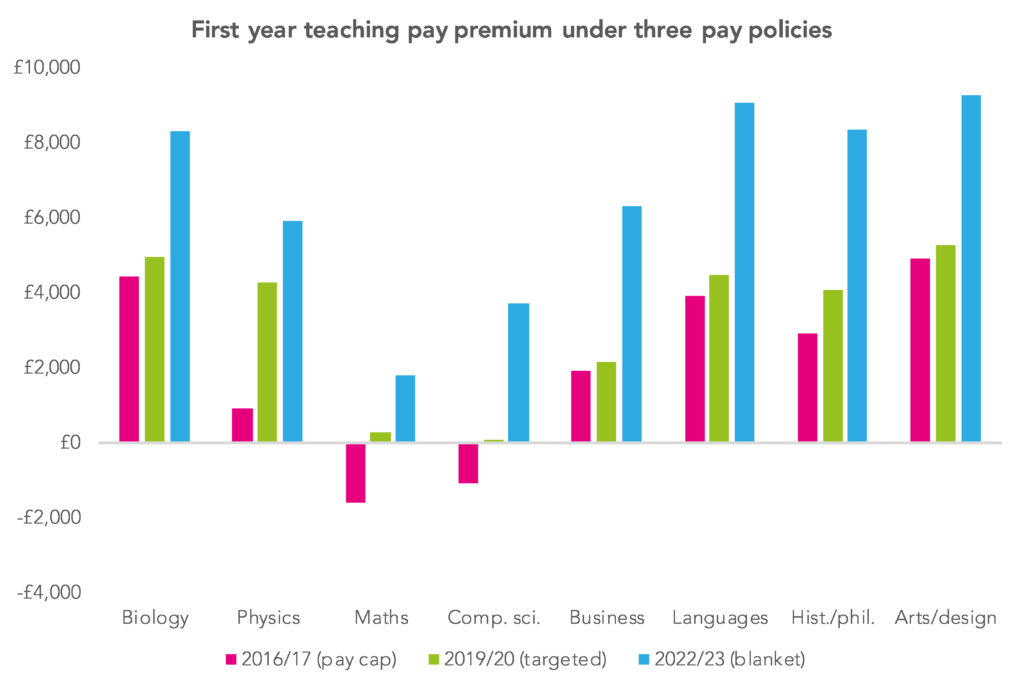

To illustrate this, the chart below shows subject-specific first-year pay premiums – between teachers and all graduates in a particular degree subject – under three different policy regimes. Teacher pay is equivalent to the main pay scale minimum, outside London.

The pink bars represent the situation in 2016/17, at which point years of public sector pay constraint meant maths and computer science graduates could expect to start on less as teachers than they would doing other jobs.

By 2019/20 – shown by the green bars – increases targeted specifically at shortage STEM subjects[1] had all but eliminated the first-year pay gap for maths and computer science, while introducing a sizable first-year teaching premium for physicists.[2]

The blue bars show the situation we might see in 2022/23 with the £30k minimum starting salary, reiterating the point that all subjects will see a first-year teaching premium under the new policy. This second chart also brings out more clearly the way in which the blanket pay rise will affect non-STEM subjects.

Remarkably, by 2022 language graduates can expect to earn around £9,000 more in a single year by entering teaching. This may be no bad thing, since the government has missed foreign language teacher recruitment targets in each of the last five years.

Even for history, however, where there is currently no national shortage, graduates can expect to earn £8,000 more in their first year of work as teachers.

Nobody can begrudge teachers a pay rise, particularly after years of public sector restraint. But it is reasonable to ask whether a blanket approach represents the best use of taxpayer money. After all, every pound spent incentivising recruitment to non-shortage subjects is a pound not spent on CPD, SEND or the NHS.

Why the splurge? At time like these, perhaps it’s not possible to put the politics aside.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. Maths and physics payments provide £2,000 per year extra in the first two years of the career for teachers in this cohort. Teacher student loan reimbursements compensate science and computer science teachers for their loan repayments.

2. Of course, in subjects such as these, entrants aren’t all required to have a degree in the subject they will teach.

It is essential to make blanket increases as teaching is widely perceived as badly paid and most people won’t even get as far as investigating actual starting salaries unless they perceive teaching is an option.

Shortage subject should be targeted first to plug the gaps before splashing out surplus subject maths and computer science Face massive shortages as they can go into industry and earn more