How much control should teachers have over what happens in their own classroom? This question has become something of a hot potato over the last few years. The National Education Union has, for instance, suggested that central control only serves to “deepen the crisis in our schools”. There has been particular ire about the relaunch of Oak National Academy (£), with grave warning about the impact that this may have on teacher autonomy.

But, when teachers do have more control over what happens in their own classroom, do pupils outcomes improve?

In a new academic paper being published in the British Educational Research Journal, Sam Sims, Andrew Morgan and I investigate this issue.

TALIS video study

We do so by drawing upon data from a sample of mathematics teachers from across eight countries who completed a questionnaire asking about how much control they have over various aspects of their classroom (amongst other things).

We are then able to link their responses to a range of outcomes amongst the pupils they teach, including their test scores, academic interest and self-confidence. Likewise, we can see if such teachers are also happier in their jobs.

No evidence of a link between teacher autonomy and pupil outcomes

A summary of our headline results can be found in the table below. This illustrates the difference in outcomes amongst pupils taught by teachers who report high rather than low levels of autonomy over what happens in their classroom.

Overall, it’s a whole lot of nothing! All the effect sizes that we found were below 0.05 (i.e. very small in terms of magnitude) and not statistically significant.

Similar results are then found for both novice and more experienced teachers, and when we look at the control teachers report having over different aspects of the class environment (e.g. discipline, lesson content, teaching methods).

Teacher autonomy and job satisfaction

But what about outcomes for teachers?

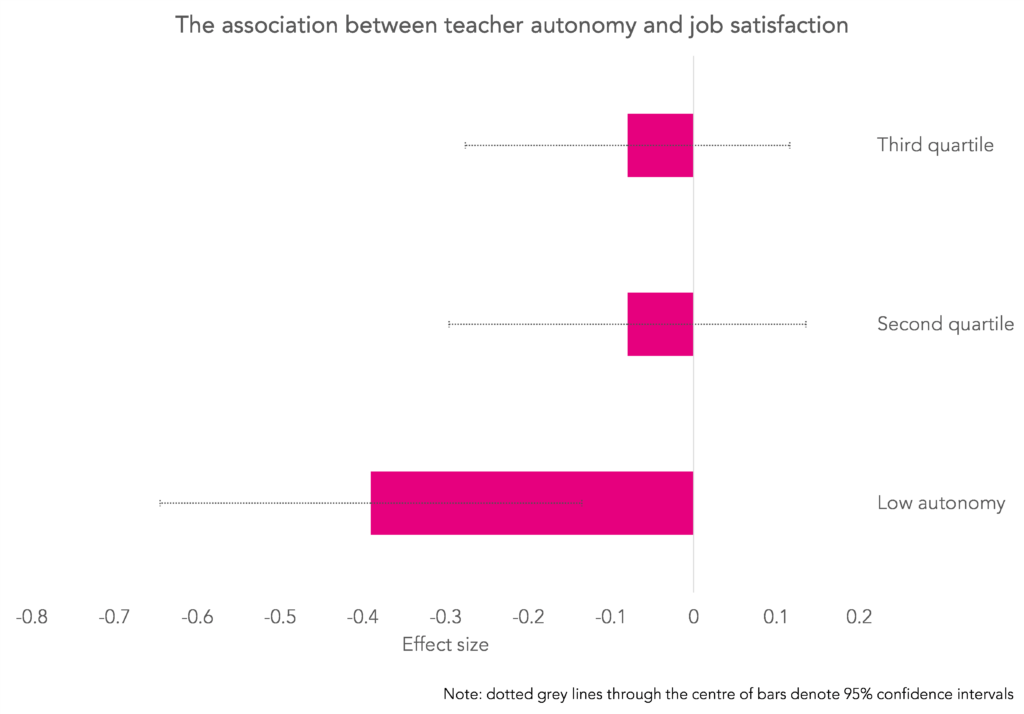

Within our paper, we are also able to look at the correlation between autonomy and teacher job satisfaction. These results are presented in the chart below. It looks at the difference in teacher job satisfaction (in terms of an effect size) relative to teachers who report the highest levels of autonomy.

For most teachers, there is again no discernible difference in job satisfaction; teachers with average versus high levels of autonomy report being equally satisfied in their jobs.

However, teachers with very low levels of autonomy do report substantially lower levels of job satisfaction as well (a difference of around 0.4 standard deviations). This suggests that a high degree of central control over what happens in the classroom may impact how content teachers feel with their work.

How much autonomy should teachers have?

Our findings suggest that the general presumption should be against introducing significant constraints on autonomy, on the grounds that this may demoralise the teaching workforce. However, the existing evidence also suggests two important caveats.

First, constraining early-career teachers’ autonomy by providing evidence-based guidance on teaching may have some benefits for pupils. For example, the recently introduced Early-Career Framework in England specifies an evidence-based framework for what early-career teachers should know and be able to do to teach effectively.

The second way in which it might be worth overturning the presumption against autonomy is where there are programmes which constrain autonomy but have been shown in rigorous evaluations to improve pupil outcomes. For example, many countries legally mandate the teaching of reading via synthetic phonics, due to the strong supporting evidence. In such cases, the demonstrable benefits for pupils may make the trade-offs with teacher job satisfaction worthwhile.

Keen to read the article but the link to the pre-print doesn’t seem to work – at least, I can’t find the article! Would be grateful for a copy. Thanks.

Hi Jenny. Here’s a better link https://bera-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/berj.3892

Interesting article, but it would be helpful to know how much variation in teaching the opportunities for autonomy produced in the classes concerned. I also wonder if the results would be different in a different subject. I can imagine that in some subjects the range of different approaches to teaching a given topic might be more significant than in Maths, and hence there might be a different impact.

Completely agree on the point about a different subject. We can’t generalise beyond maths. Likewise, we looked at secondary – could be different for primary!

Yes, the icensef professional teacher needs autonomy in the classroom.

Do you know of any research on whether teacher workload correlates with level of autonomy?

Unfortunately not. The study didn’t collect data on teacher working hours. It might have a part-time indicator though; something I will check out.

Given the relatively strict nature of mathematics curricula surely English would be a richer source for study? Indeed a range of subjevts would be ideal.

Is this the same across different sectors early years, primary and secondary?

We are all aware that we cannot afford the pay what teachers deserve. Job satisfaction is a major factor in keeping good teachers.

I have been wondering about teachers autonomy to teach. I can’t see how this can be achieved with the current teaching prescription. In my view this skews your results.

While most children do well on phonics it is not accessible to all. Dyslexic or deaf children are disadvanged.

Very interesting, but would the findings be the same or similar for teachers of other subjects? Research into the effectiveness of mathematics textbooks tends to show results that do not hold for other subjects.

This is very interesting, thank you John… as with your other analyses, clear application of statistical methods, but then a step-back recognising that statistics can only go as far as the data… in this case recognising that there may be an effect on teacher morale, and that this may very plausibly have negative impacts on achievement. Like!