The recent green paper on special educational needs and disabilities signaled a forthcoming call for evidence on unregistered provision, such as one-to-one tuition and work-based placements.

This underlines a lack of evidence at a national level about the use of unregistered provision, something which we have written about previously. Local areas may have a good idea of provision in their patch but there does not appear to be any systematic assembly of local offers into a national picture.

This in turn hinders development of policy to improve alternative provision. Other reviews, such as the Education Select Committee investigation into exclusions , have raised concerns about the quality of some unregistered providers.

In this blogpost we will take a look at what we do and don’t know about use of unregistered alternative provision.

We look at two types. Firstly, provision commissioned by local authorities. Secondly, provision commissioned by schools. We know much more about the former than the latter.

Local authority alternative provision

As we wrote in a previous blogpost, there has been a rise in recent years in the number of young people in alternative provision (AP) commissioned by local authorities (LAs). This refers to education outside the state-funded school system for which LAs pay fees. Most of this relates to children with Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans attending independent schools. As the number of EHC plans has increased, so too has the number of young people educated outside the state-funded school system.

However, we also showed that some young people in LA commissioned AP were not attending schools.

Using the alternative provision census, which is completed by local authorities every January, we can see the number of young people for whom LAs are paying fees for education but who do not go to schools or colleges. We define this as unregistered alternative provision (UAP).

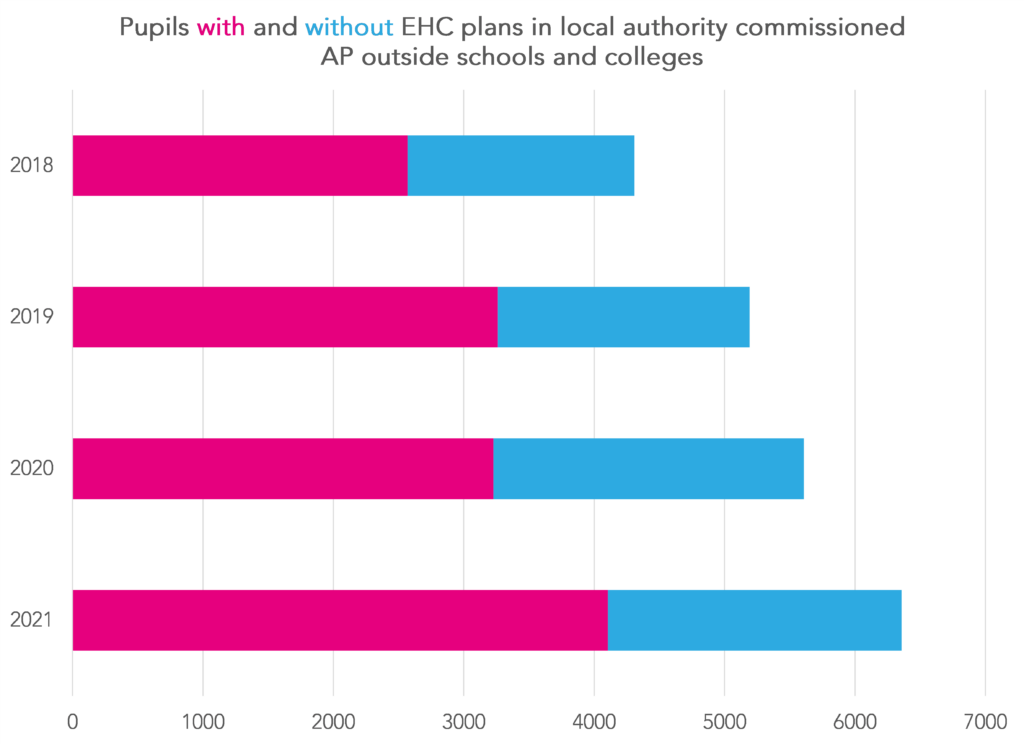

This shows that the number of young people in UAP commissioned by LAs increased from 4,300 in 2018 to 6,400 in 2021. Of this latter number, 65% had EHC plans.

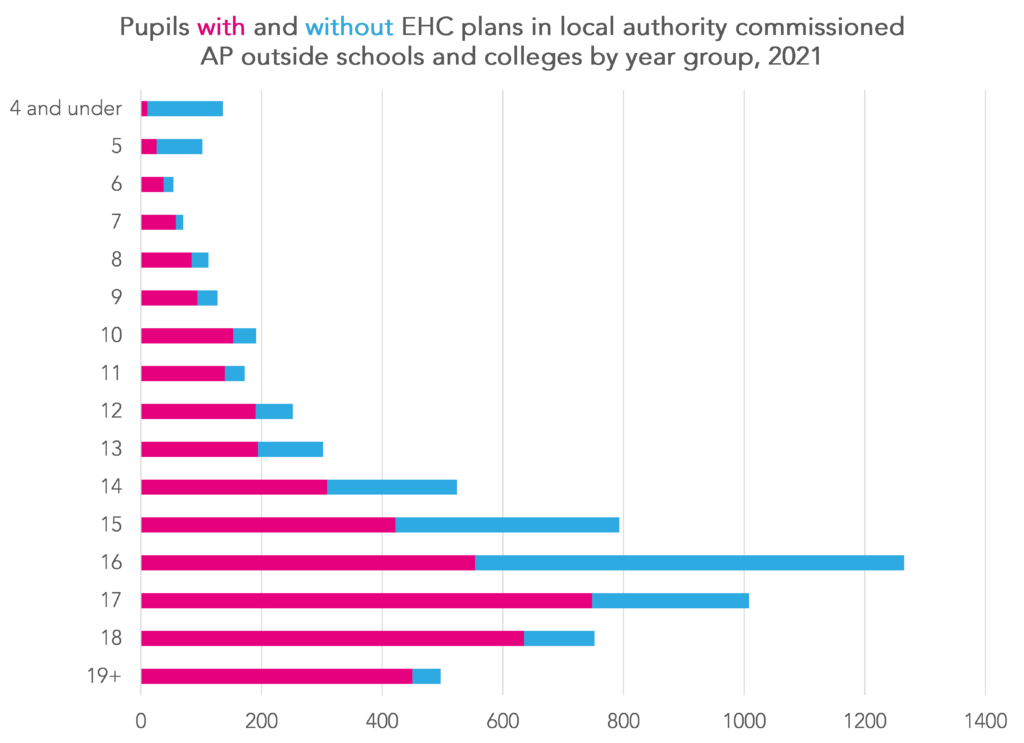

The following chart breaks down the 6,400 young people by age at the end of the 2020/21 academic year.

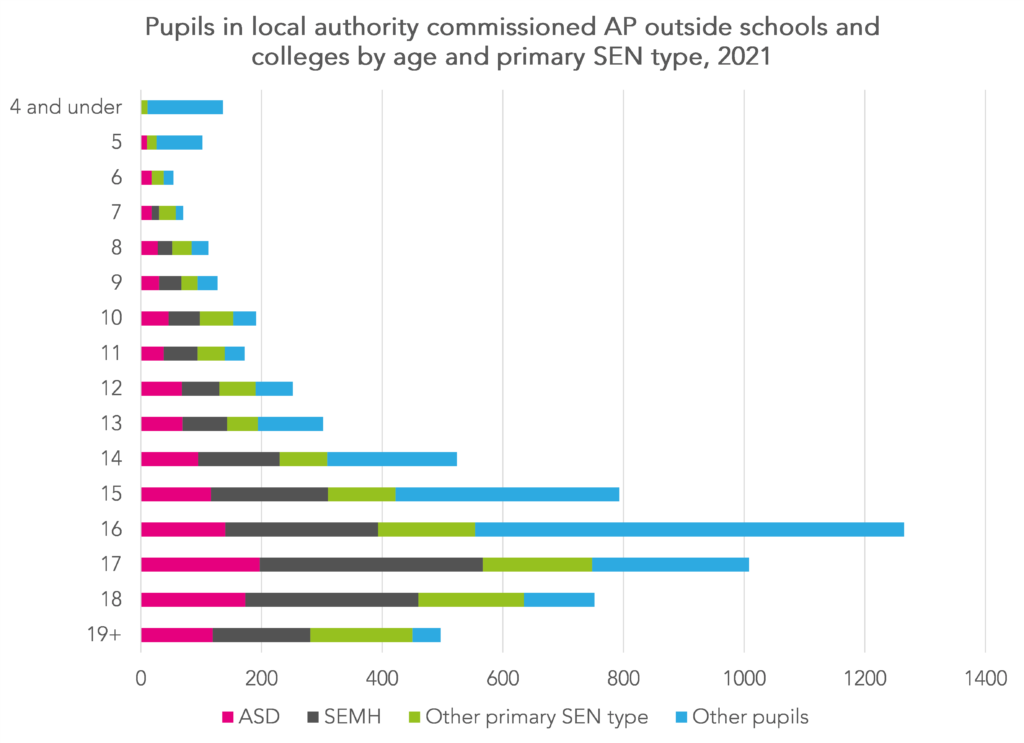

Disaggregating the group of young people with EHC plans by primary SEN type shows that there are two main types of need: Autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) and social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs.

The majority of young people (60%) in UAP in January 2021 were aged 15 to 18. 62% were of compulsory school age (5 to 16).

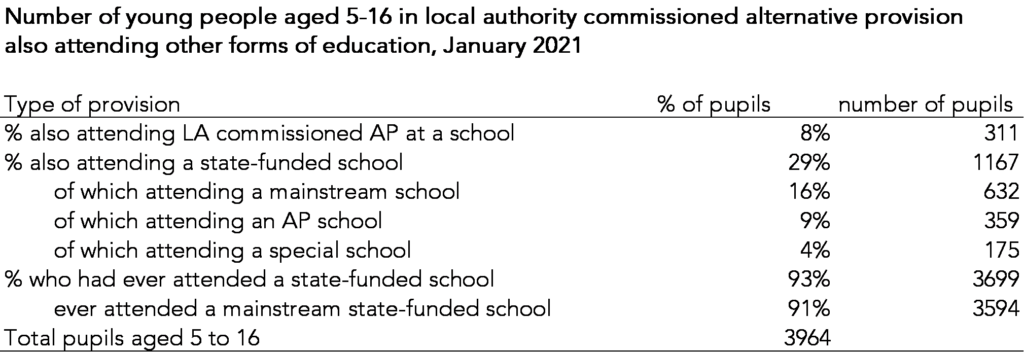

The table below shows how many of the compulsory school age group also attended schools as well as other forms of education.

Around 29% of those of compulsory school age were also enrolled at state schools at the same time as being in LA commissioned UAP. This might suggest that they attended UAP part-time.

The vast majority of young people- 93%- had been enrolled at a state-funded school at some point during their school career. Some of those who hadn’t may have moved to England during compulsory school years.

The chart below shows that 16% of young people in LA commissioned UAP had previously been permanently excluded[1]. This rate exceeded 25% among 15 year olds.

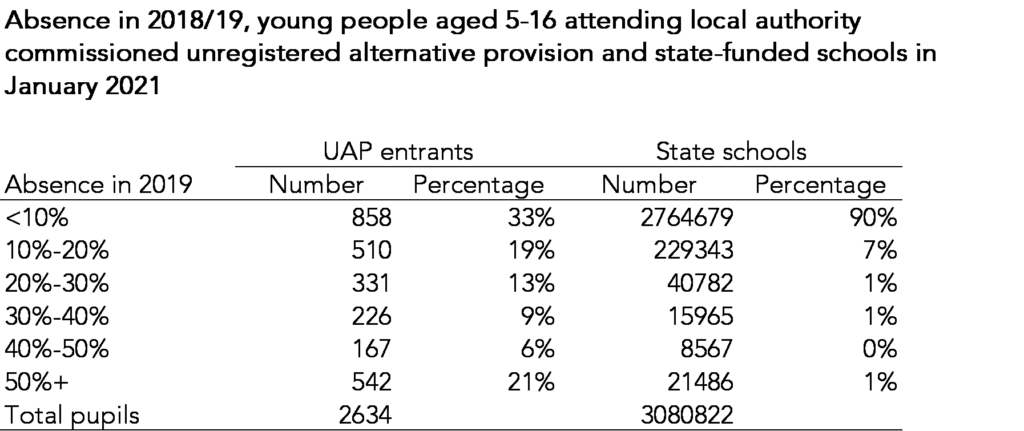

Those in LA commissioned UAP are also far more likely than other pupils to have been persistent absentees. To look at this we use absence data for the 2019 academic year, the last to have been unaffected by COVID-19. We restrict our analysis to 2,600 young people who attended state schools in 2019 but who subsequently entered LA commissioned UAP[2]. In the table below we compare their absence in 2018/19 to pupils who were attending state schools in 2020/21[3].

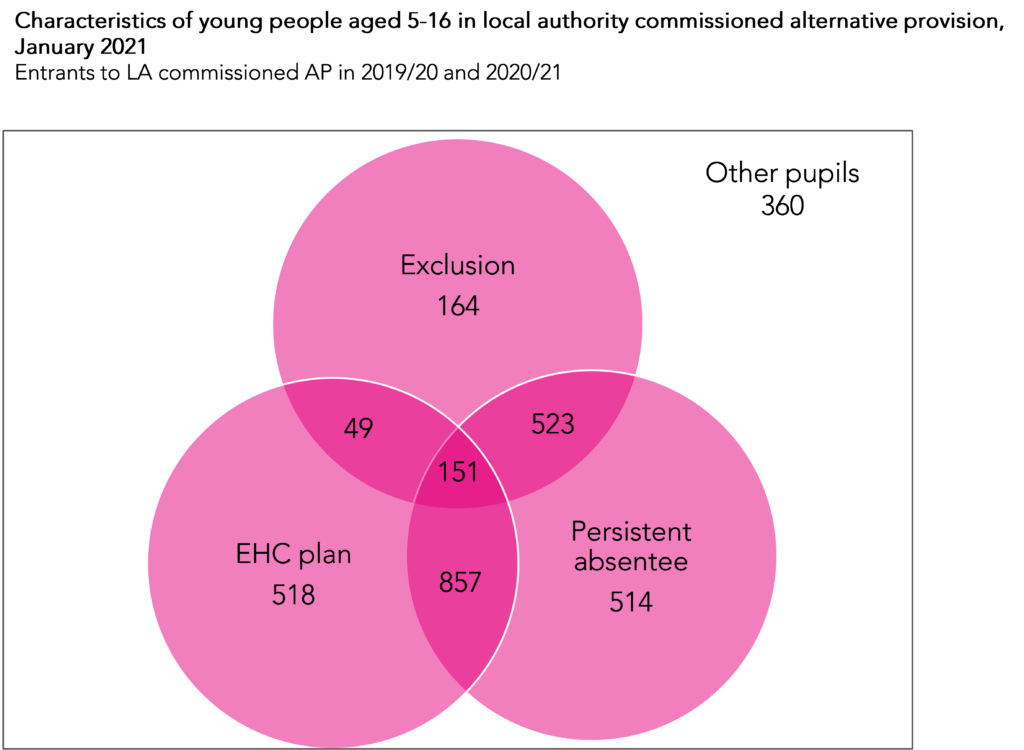

The venn diagram below shows the overlap between three key characteristics of young people in LA commissioned AP: permanent exclusion, persistent absence (in 2018/19) and having an EHC plan. We again restrict our analysis to those who first entered LA commissioned AP in 2019/20 or 2020/21 [4]. 89% of pupils fall into at least one of the three groups, though fewer than 5% fall into all three categories.

This analysis does not reveal much about what type of unregistered provision young people are attending. Although the AP census collects some broad categories, the last time we looked these were not very informative. The vast majority of young people were in “other registered provision”.

Finally, we’ve only looked so far at a set of snapshots taken in January. We haven’t looked at young people moving in and out of unregistered provision during the academic year.

School commissioned alternative provision

We know far less about the extent to which schools commission alternative provision with unregistered providers.

Ofsted carried out a survey of 165 schools in 2016 into their use of off-site alternative provision. This generally found that schools worked well with unregistered providers and that they were safe. However, it also found that some unregistered providers were contravening regulations about registration and that some pupils were not receiving a full-time education.

This review only a looked at a small number of schools. National data on the number of pupils placed in UAP has not hitherto been collected.

The Department for Education (DfE) have begun to address this information gap by asking schools to provide data on alternative provision they commission (both registered and unregistered) via School Census on a voluntary basis. This was collected for the first time in January 2022 although no analysis has yet been published.

Summing up

Over 6,000 pupils were in unregistered alternative provision commissioned by local authorities in January 2021. The vast majority of these pupils had an EHC plan or had been permanently excluded or a been persistent absentee.

Much less is known about the number and characteristics of young people in school commissioned alternative provision.

The national datasets available to government and accredited researchers tell us little about what sort of unregistered provision young people are attending. It is straightforward to collect data on schools because they exist on registers with identifiers. There is (obviously) no equivalent register of unregistered AP settings. But perhaps something like this is necessary for organisations in receipt of public funds.

- Due to small numbers, exclusion data for young people aged 7 and under is not shown

- 51% of pupils in LA commissioned AP in 2021 were observed to first enter it in 2020/21 and a further 24% in 2019/20.

- Again, using absence data for 2018/19 for this group

- We have included here individuals who could not be linked to 2018/19 absence data, increasing the sample size to 3,100.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment