A significant proportion of school inspections in England are conducted by contractors – many of whom are staff employed by a school, often in a school leadership role.

These individuals are privy to certain inside knowledge and training that are not available to most schools. For instance, they will receive regular training about the inspection framework, and what inspectors should (and should not) look for when they are judging a school.

This may lead to concerns about the potential advantages this brings to the school where these individuals work. For instance, in October last year, a storm broke out over the leak of some Ofsted training material, with claims that individuals with access to them (such as contracted inspectors) would have an unfair advantage in the inspection process.

Is there any evidence to back up this view? In a new academic working paper published today – which is part of a wider project funded by the Nuffield Foundation into the consistency and reliability of Ofsted inspections – we take a look.

What we looked at

One of the reasons no one has looked at this before is a lack of data.

However, Schools Week recently obtained the names of the schools where Ofsted inspectors work and very kindly agreed to share the information with us for research purposes. This list refers to those individuals who were working as inspectors in October 2022.

We have then cross-referenced this information with data routinely published by Ofsted and the Department for Education about schools. This includes inspection outcomes in the 2022/23 academic year.

Of the 6,133 inspections conducted last academic year, only 150 (2.4%) were of a school that employs an Ofsted inspector. This is, in other words, small fry in terms of the bigger picture of Ofsted’s work.

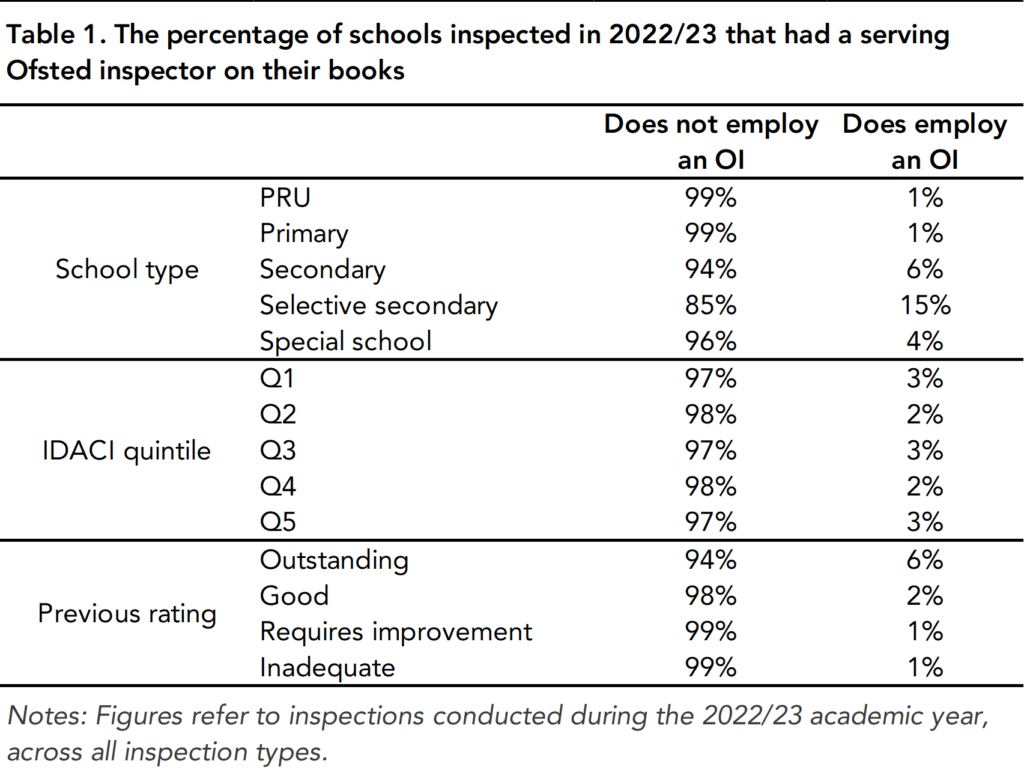

However, as Table 1 illustrates, this is not evenly distributed across schools. 15% of the grammar schools inspected in 2022/23 had an Ofsted inspector on their books, and 6% of other (non-selective) secondary schools. This compares to just 1% of primary schools (probably because they are smaller in size and there are lots more of them).

Schools with a prior Outstanding rating are also more likely to employ an Ofsted inspector (6% of those inspected in 2022/23) though, interestingly, there doesn’t seem to be much variation according to the socio-economic intake of the school.

Do schools employing an Ofsted inspector get better inspection outcomes?

In a word, yes.

Table 2 illustrates the Overall Effectiveness judgement awarded to schools with and without a serving Ofsted inspector on their pay role.

Those employing an inspector were much less likely to be awarded an Inadequate or Requires Improvement rating (8% for those with, compared to 24% for those without). They were also more likely to be awarded an Outstanding judgement (20% versus 7%).

Now, some of these raw differences in outcomes are related to the characteristics of schools that employ Ofsted inspectors; as Table 1 illustrates, grammar schools and those already with an Outstanding rating have a disproportionate share.

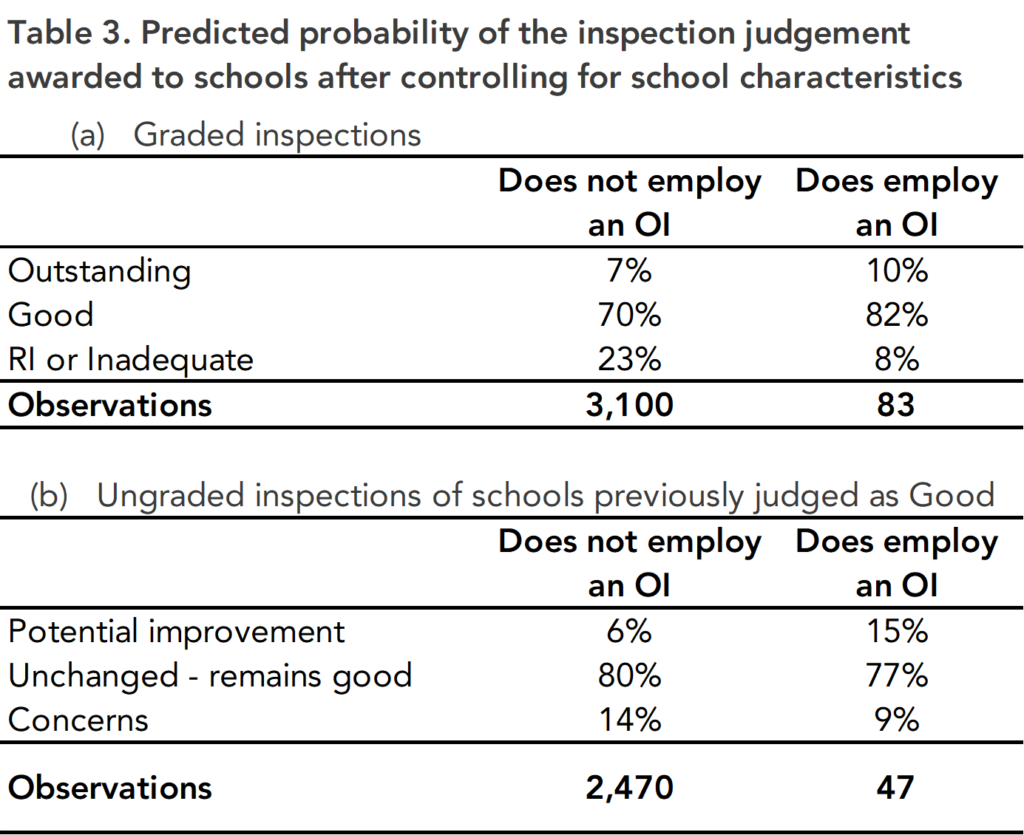

However, in our academic paper we probe this issue by controlling for differences in such school characteristics, plus other measures including school absence rates and historic examination performance. We find that schools that employ an Ofsted inspector are still less likely to be rated as Requires Improvement or Inadequate, although the difference between Good and Outstanding grades is greatly reduced.[1] Table 3 provides further details.

Why does employing an OI help schools to get a better inspection outcome?

We don’t know for sure but speculate about four possible mechanisms.

The first is that working and being trained as an Ofsted inspector could be one of the best bits of professional development a teacher or school leader ever receives. They take what they learn from their training – and on-the-job experience – then apply it to their own school. In other words, by working as an OI, they genuinely make their school a better place for young people. We have, however, checked Ofsted’s Parent View data and found no evidence that parents rate the schools where OIs work more highly.[2]

The second possibility is similar, though somewhat less starry-eyed. The training and inside knowledge that school leaders gain help them to know and understand what inspectors are looking for – but are really more about appearance rather than improving school quality. In other words, they get to know what “looks good” – and what hoops schools need to jump through – to get a top inspection grade.

Third, there could still be an element of selection effects. Ofsted may only employ the very best people, who would significantly improve the school in which they work regardless of whether they gain such inside knowledge or not. In the future, we will be able to control for future outcomes achieved by pupils in these schools to probe further where this is the case. However, from what we can observe (and control) in the data currently, our feeling is that this explanation is unlikely. We also note the study published by EPI on Wednesday, illustrating how more “effective” headteachers actually don’t seem to get better inspection judgements.

Finally – and perhaps most controversially – a professional network effect could be at play. Ofsted inspectors work in regional teams, will inspect schools together and (presumably) attend training together. It is only human nature for them to get to know their peers – including potentially those who end up inspecting their schools. Although Ofsted obviously manages direct conflicts of interest, a professional networking effect may still be apparent. Though, out of our four explanations, our feeling is this is the least likely.

In reality, the differences in inspection outcomes reported in Tables 2 and 3 are likely driven by some combination of the above. At the moment, it is not possible to disentangle their separate effects. Only if Ofsted provide us – and other researchers – with further data will we get to the bottom of such issues.

[1] We have also tested the sensitivity of our results in various other nerdy ways, including extending the sample of inspections to also include the 2021/2022 academic year, and examining outcomes for short inspections of previously Good schools as well.

[2] Using data from the 2022/23 academic year, in schools that employ an OI, 83% of parents say they would recommend the school. This is almost identical to the percentage in schools that do not employ an OI. This suggests that anything genuine “improvement” OIs make to their own schools are not visible to parents.

Leave A Comment