Mental health has become a major challenge in schools, with some studies indicating that low levels of wellbeing may be a bigger challenge in England than other countries.

Previous research has suggested that children from disadvantaged social backgrounds are two to three times more likely to develop such problems. Yet there are certain issues – such as eating disorders – which have also been linked to higher levels of academic achievement.

In a new academic working paper I explore differences in hospital contacts made by young people from different socio-economic backgrounds with different levels of academic achievement. One of its goals is to explore the interaction between socio-economic background and achievement by age to understand whether mental health issues could be a plausible mechanism driving differences in their later academic attainment.

This blog focuses on self-harm, with other issues (alcohol/drug abuse; eating disorders) explored in the paper.

This is the second paper from my Nuffield Foundation project exploring the outcomes of high achieving children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. I’ve already blogged about my findings from the first paper.

Data

The study draws on ECHILD; data matching information from the National Pupil Database (NPD) to Health Episode Statistics (HES). I analyse data on hospital contacts made between age 11 and 20 from three school cohorts, born between September 2000 and August 2003.

As part of my analysis, I created a socio-economic status scale, based upon the number of years the young person was eligible for Free School Meals and the percentage of children living in poverty within their local area.

Figure 1 illustrates differences in hospital contacts made due to self-harm according across different socio-economic groups. The most advantaged group (bottom decile) is the lightest dashed line, while the most disadvantaged group (top decile) is the darkest solid line. Results are presented in terms of contacts made per 1,000 children.

There are two interesting features to note.

First, for all socio-economic groups, there is a steady rise in hospital contacts due to self-harm between Year 7 (age 11/12) and Year 10 (age 14/15), at which point the rate peaks. Contacts with hospitals due to self-harm then falls slightly – particularly amongst the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups – thereafter.

Second, the rise in hospital admissions related to self-harm is particularly stark for young people from disadvantaged social backgrounds. For the most disadvantaged 10% of pupils, the rate of hospital admissions increases from 1.5 to 10.2 per 1,000 children between Year 7 and Year 10, compared to an increase from 0.3 to 4.0 for the most advantaged socio-economic group. After Year 10, the socio-economic gap in self-harm narrows again.

Figure 2 enriches this picture by illustrating how self-harm rates compare across high and low achieving children (top/bottom quarter of Key Stage 2 scores) from advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds (top/bottom quarter of my socio-economic background scale).

While the self-harm rate is highest – and incline steepest – for low achieving children from disadvantaged backgrounds (darker dashed line), the darker solid line for high achieving children from equally disadvantaged backgrounds is not far behind. This indicates that socio-economic disadvantage drives higher rates of self-harm amongst both higher and lower achieving pupils. Likewise, the trajectory of self-harm rates amongst the most advantaged pupils do not seem to vary much by their level of prior achievement.

In future work, I am planning to explore whether these patterns also vary by gender, given potential differences in mental health (including self-harm patterns) across high-achieving boys and girls.

The implications for schools

These results provide one example of the broader set of challenges that disadvantaged young people face during adolescence. Schools serving disadvantaged communities then, of course, are faced with helping young people to manage these challenges as they attempt to help them learn and develop.

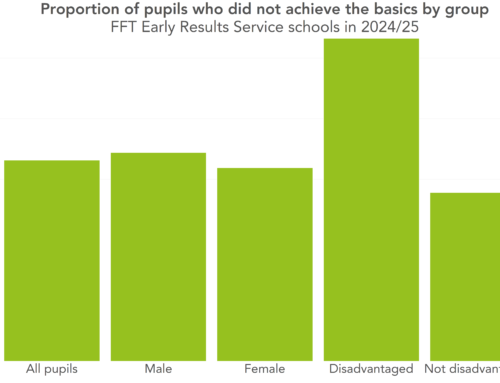

This perhaps also helps to contextualise some of the measures often used to make judgements or inferences about schools. For instance, given these results, it is unsurprising that schools with greater numbers of disadvantaged pupils have lower levels of attendance and Progress 8 scores. Given the complex array of difficulties many disadvantaged young people face – including with their mental health – one should always treat somewhat simple accountability metrics for the schools serving these communities with particular care.

Further reading: Jerrim, J. (2024). Hospital contacts amongst high achieving adolescents from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

A fascinating study that all school leaders and education policy makers should be taking note of. For me, it raises two important points above all others.

The need for:

swift improvement in the connectedness of the various social services that support young people;

greater consideration to be given to the nature and ethos presented by secondary school environments, especially with regard to the way pupil management systems strip away the opportunities for personal connection with trusted adults that children have previously been used to.