Regular readers will know that we’ve been using attendance data to monitor the rate of exclusions and suspensions in schools in advance of official statistics from the Department of Education.

Back in November, we looked at exclusions and suspensions over the 2023/24 academic year. Official statistics will only be published in the summer.

Official statistics for the previous year (2022/23) show that exclusion and suspension rates have been increasing since the pandemic. Our analysis suggested that these trends continued in 2023/24.

We now look at what happened in the Autumn term of 2024/25.

Data

Pupils who are permanently excluded or suspended but who remain on the school roll are marked as code E in registers for up to five days. From the sixth (consecutive) day, alternative provision is supposed to be arranged.

Using attendance data for Autumn 2023/24 and 2024/25 supplied by 9,000 schools subscribing to FFT attendance tracker, we can summarise rates of absence due to exclusion and suspension for both years.

What we cannot do is distinguish between spells that are due to suspension and spells that are due to exclusion (or more accurately, spells that will result in due course in permanent exclusion).

Comparing our method to published statistics

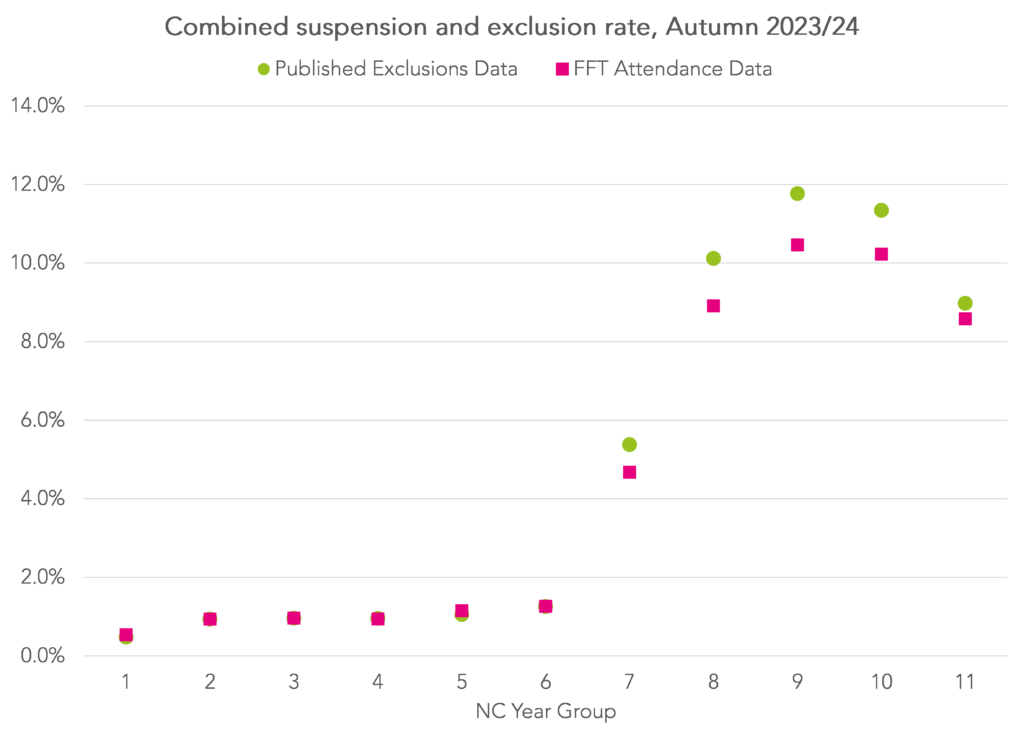

As usual, we begin by comparing our figures with published official statistics, the most recent of which are for the Autumn term 2023/24.

The figures we produce are equivalent to the sum of the permanent exclusion rate and the suspension rate, in other words the total number of exclusions and suspensions divided by the total number of pupils. Given that suspensions tend to outnumber permanent exclusions by a rate of approximately 20 to 1 then our figures are mainly of suspensions.

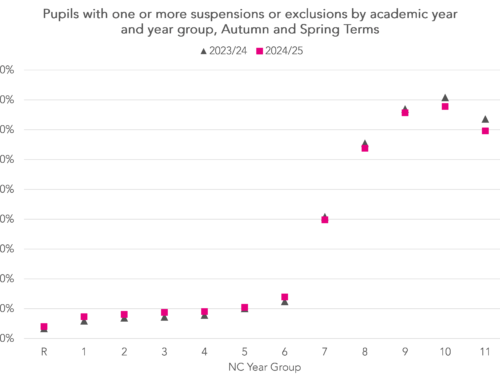

We show our calculated figures for Autumn 2023/24 alongside the published DfE figures in the chart below.

This pattern is typical when we do sort of analysis. Our figures are fairly close to DfE figures but, if anything, are a bit lower, particularly for Years 8 to 10, the year groups with the highest rates. There may be various reasons for this. For example, If a pupil returns from suspension and is suspended again the same day we would count that as one suspension rather than two.

Consequently, our figures for Autumn 2024/25 might be slightly under-estimated.

Suspensions in 2024/25

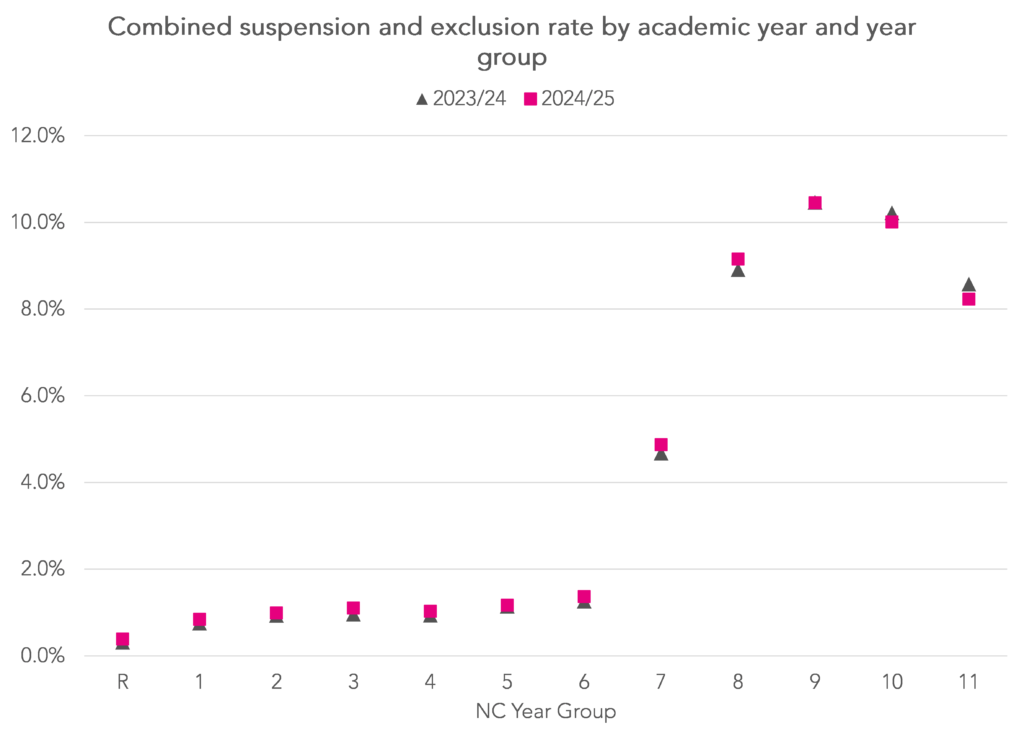

Repeating our methodology for Autumn 2023/24 and 2024/25, we see little change in the rate of suspensions and exclusions across all year groups.

Among the primary year groups, we see a small increase in the combined exclusion and suspension rate of 0.1 percentage points (pps).

Among secondary year groups, we see slight increases in the rate for Year 7 and Year 8 (0.2pps and 0.3pps respectively), no change for Year 9 and decreases for Years 10 and 11 (0.2pps and 0.4pps respectively).

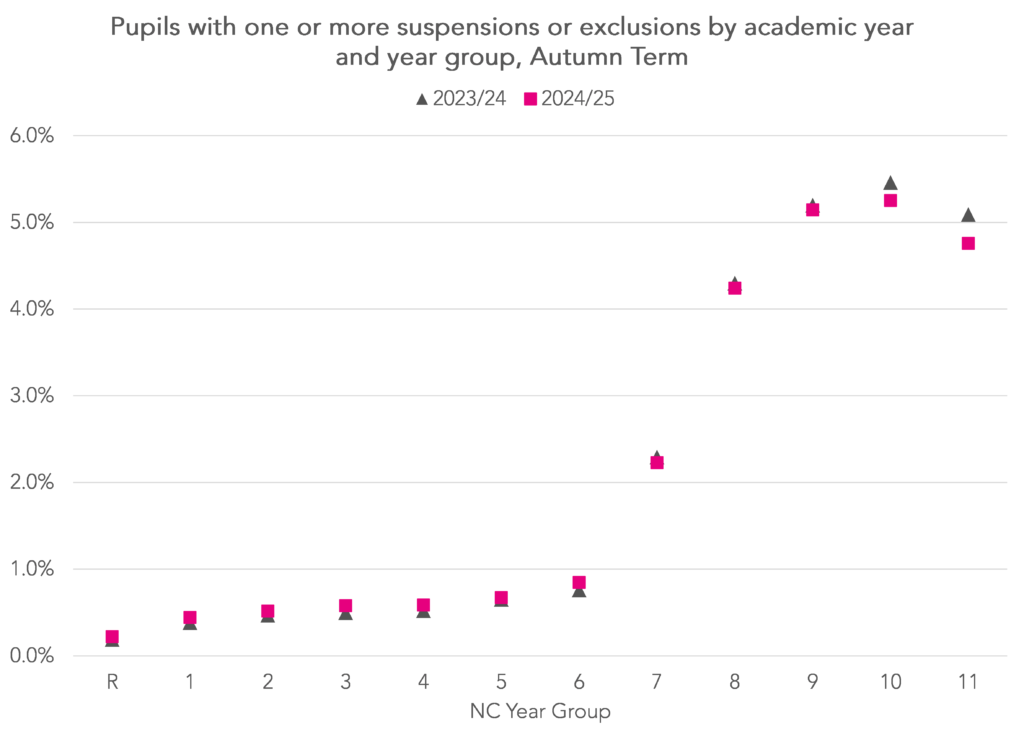

The suspension rate is the number of suspensions divided by the number of pupils so a rate of 20% does not mean that 20% of pupils have been suspended. Some pupils will be suspended more than once.

But we can also summarise the percentage of pupils who are suspended or excluded at least once.

For most year groups, 2024/25 rates were very close to those for 2023/24 and slightly lower for pupils in Years 10 and 11.

Disadvantaged pupils

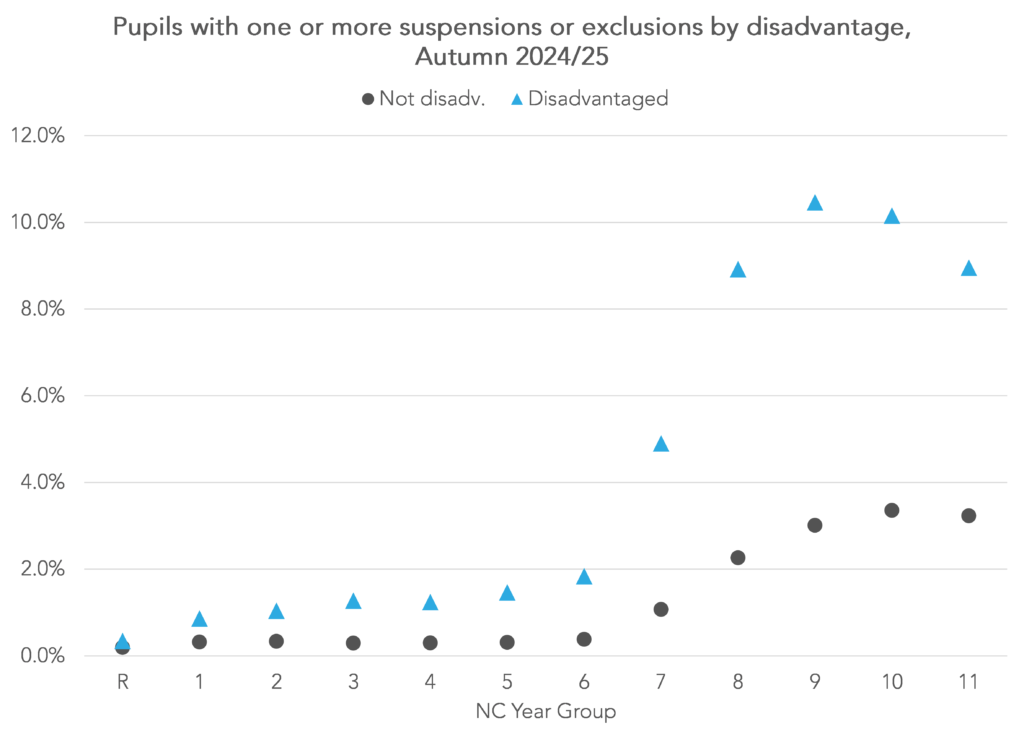

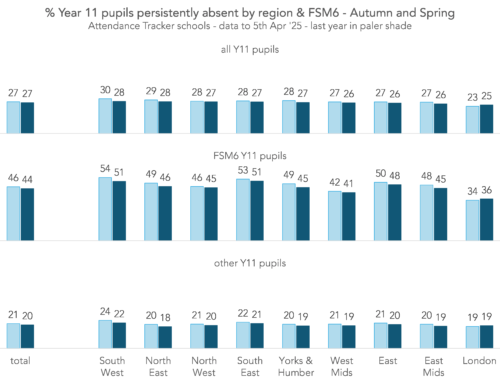

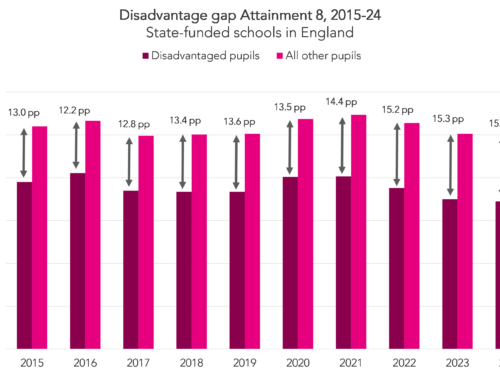

We continue to see stark differences in the percentage of disadvantaged pupils suspended or excluded at least once compared to their peers.

10% of disadvantaged pupils in Years 9 and 10 were suspended or excluded at least once in the Autumn Term.

Disadvantage, along with a previous history of social care and a previous history of suspension are the biggest risk factors of exclusion.

Summing up

Published DfE statistics for the 2022/23 academic year showed that suspensions reached record levels and our analysis for 2023/24 suggests that they were higher still.

Early data for the 2024/25 academic year suggests that the rate of increase is at least beginning to slow. A peak may have been reached, or is close to being reached.

It remains the case though that disadvantaged pupils are disproportionately (far) more likely than other pupils to experience exclusion or suspension.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

The rhetoric around suspensions and attendance is appalling. If schools wish to improve either then wellbeing has to be the first priority not the last.

Irony of child eventually suspended and not attending by going on holiday. Parents fined. They missed learning in school about the country they went on holiday to and time needed with parents and siblings.

Anecdotes don’t inform us the way statistical evidence does, but it does depend upon what we measure and compare when choosing policy objectives. We will look back on our education system and call it abusive and wonder why we allowed people with poor understanding of children and families or education or even the future needs of business, ever get hold of policy. Higher exclusions of those with multiple unmet needs signposts the failure if not already obvious to professionals.