The government’s recent curriculum and assessment review has proposed introducing new “diagnostic” tests at Year 8 in writing and maths —a tool intended to help teachers identify pupils’ strengths and weaknesses across different areas of a subject. On the surface, this sounds like a smart idea: more granular data could, in theory, help schools better target support and teaching. But as our recent Nuffield Foundation–funded report shows, creating genuinely diagnostic sub-domain maths scores is far more difficult than it might appear.

Our project explored whether it was possible to produce reliable “sub-domain” mathematics scores—such as separate measures for number, geometry or algebra—using data from the Key Stage 2 (Year 6) SATs. These tests already contain questions spanning different areas of the maths curriculum, so in principle, it seemed feasible to use them diagnostically (even though they were not explicitly designed for this purpose). However, we ended up concluding that for the current assessment design, such scores would be of little practical use to schools.

Why sub-domain scores sound helpful—but rarely are

Sign up to our newsletter

If you enjoy our content, why not sign up now to get notified when we publish a new post, or to receive our half termly newsletter?

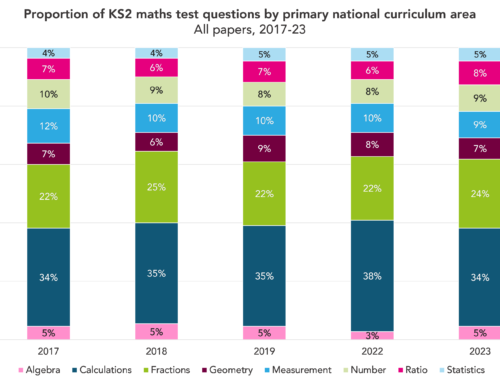

Schools are often keen to understand which aspects of mathematics pupils struggle with. The Department for Education’s Analyse School Performance tool already provides breakdowns by topic for the Key Stage 2 tests, showing, for instance, the percentage of correct responses in geometry versus calculations. But these are just raw percentages, with no indication of how reliable they are. Our study showed that even when applying advanced statistical techniques, which corrects for measurement error, the apparent differences between domains largely disappear. (You can read more about our findings here.)

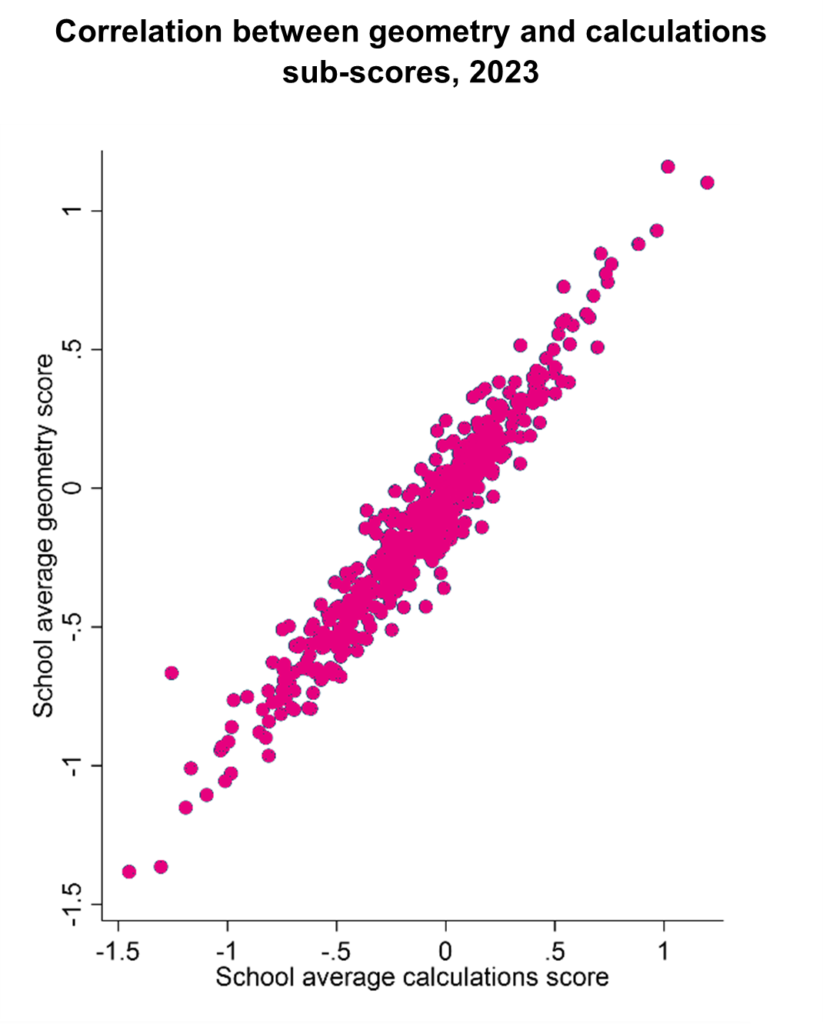

Put simply, schools that do well in one area of maths tend to do well in all of them, and vice versa. The chart below illustrates this: each dot represents a school, plotting its average geometry score against its average calculations score. The near-perfect diagonal line tells the story—geometry and calculations scores move almost in lockstep.

Across our sample of 500 schools, the correlation between domains was about 0.98. Even at the pupil level, it was around 0.91. That means the tests simply don’t provide enough independent information to distinguish whether a pupil (or school) is relatively stronger in one area of maths than another. The same pattern appears in TIMSS, the international maths assessment designed with much broader content coverage. For instance, in TIMSS the school-level correlations between domains such as geometry and number are still above 0.98 (and at the pupil level above 0.9).

Why this matters for the new Year 8 test

The government’s new Year 8 diagnostic maths test aims to provide teachers with actionable insights. For that to happen, it will need to overcome the challenges that undermined our ability to extract reliable sub-domain scores from the SATs (which were not designed with this purpose in mind).

A genuinely diagnostic test will require careful, innovative design. That means:

- Sufficient test length. To reliably measure different aspects of maths, you need many items within each sub-domain. This likely means the test will involve quite a long test time.

- Adaptive delivery. A computer-based, adaptive format could help keep test times manageable by tailoring questions to each pupil’s ability.

- Robust psychometric validation. Before rollout, pilot studies must demonstrate that sub-domain scores are statistically reliable and add clear value beyond overall performance. If teachers are being asked to act on these data—focusing extra teaching time on “geometry gaps,” for example—we must be confident that these gaps are real, not artefacts of measurement noise.

- Balanced content coverage. The test would need an even spread of questions across domains, with items designed to discriminate between pupils’ strengths in each area.

Creating such a test is possible—but it’s not simple. The temptation to think that diagnostic testing just means reporting more detailed scores from a general maths assessment should be resisted. Without sufficient questions per domain, robust scaling and clear measures of uncertainty, diagnostic scores can easily mislead rather than inform.

A reality check

Our work on the Year 6 SATs shows that even sophisticated statistical modelling can’t conjure fine-grained diagnostic insight out of tests that weren’t designed for that purpose. The lesson for policymakers is clear: if we want the Year 8 diagnostic maths test to genuinely help teachers, it will need to be designed that way from the ground up—and that’s a demanding task.

So while a Year 8 diagnostic test could, in principle, provide valuable information, the technical and design challenges are considerable. Unless these are addressed head-on, we risk creating another assessment that generates more noise than clarity.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment