There’s long been interest in socio-economic inequalities in educational achievement in England. Typically, most research in this area focuses on differences in average scores. Less attention has been paid to young people at the extremes of the distribution – for instance, how achievement varies between the most able pupils from advantaged and disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds.

In my report today for the Sutton Trust I take up this challenge by comparing the achievement of England’s most able pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds in an international context.

Using data from the 2015 PISA test, the table below illustrates the science scores of the top 10% of low socio-economic status pupils within each OECD country. (Science is chosen, as the major focus of PISA 2015.)

Compared to other industrialised nations, England compares favourably in this respect.

In only Finland and Estonia do high-achieving poor children do significantly better than in England, while there are 23 countries performing significantly worse.

In fact, England is similar to many of PISA’s big hitters, performing similarly to Canada, South Korea and the Netherlands.

This is evidence of a real success story for this country from PISA and illustrates clearly how this country has a number of socio-economically disadvantaged pupils who are nevertheless of high potential.

This isn’t to say, however, that there’s no socio-economic gap between high-achieving rich and poor pupils in this country.

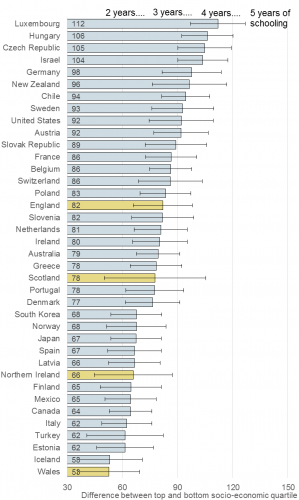

The figure below shows that there clearly is, with bright but poor pupils lagging by 82 test points – equivalent to two years and nine months of schooling – behind their bright but high socio-economic status peers.

Socio-economic gaps in children’s science skills among the highest-achievers

Notes: Thin black lines refer to estimated 95% confidence intervals. ‘High achieving’ refers to the 90th percentile. First generation immigrants have been excluded.

Yet, at the same time, there is little evidence to suggest that England stands out from other countries in this respect. In fact, in terms of the high-achievement gap, England appears to be very similar to other countries.

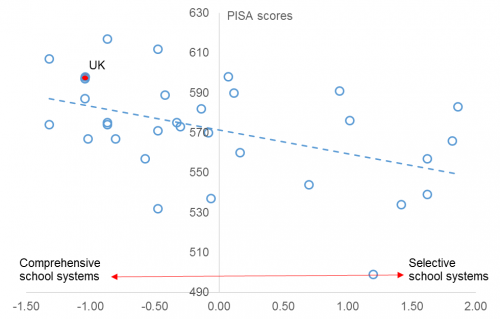

Finally, one of the arguments often made in favour of grammar schools and selective education is that they may be beneficial for disadvantaged children of high academic potential.

But is there any evidence from PISA that this is really the case?

The answer, as shown in the figure below, is a clear no.

Science performance of high-achieving disadvantaged pupils and academic selectivity of schooling systems

Notes: Sample restricted to the countries included in Bol et al. (2014). The horizontal axis provides an index of the selectivity of schooling-systems across the world, based upon Bol et al. (2014). The United Kingdom has been treated here as a single entity, as Bol et al. (2014) does not provide separate information on the selectivity index for England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. First generation immigrants have been excluded.

In fact, high-achieving poor pupils tend to do worse in PISA in countries with academically selective secondary school systems.

Given that this is an area where England is currently performing quite strongly, any expansion of selective schooling in this country may well result in a backwards step.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from Education Datalab? Sign up to our mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive our half-termly newsletter.

Leave A Comment