In education systems across the world, children are separated into different groups based upon their academic achievement. This is done in different ways.

Countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and Northern Ireland ‘track’ pupils of high and low achievement into different schools (as do parts of England – e.g. Kent – that have retained grammar schools).

Others rely more heavily upon within-school ability grouping of pupils, whether this be setting/streaming, or sitting higher/lower achieving children together within the same class.

A whole host of research has compared countries in how much they segregate higher and lower achieving pupils into different schools. But there has been little work on the extent that different countries group high and low achievers together when they go to the same school.

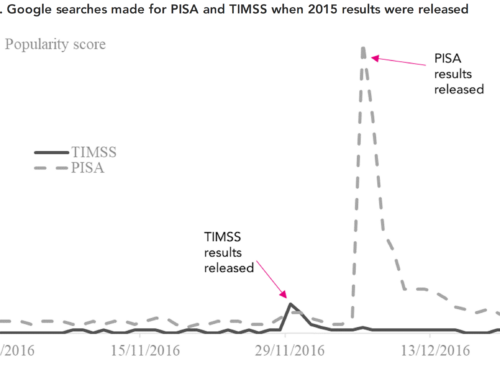

What can PISA and TIMSS tell us about this?

Fortunately, interesting information has been collected on this matter within PISA and another international study, TIMSS, which covers maths and science for pupils in Year 5 and Year 9.

In the 2015 rounds of these studies, teachers and headteachers were asked:

- Whether their school has a policy of grouping pupils of similar ability together in the same class for their lessons (i.e. whether they ‘set’ children)

- Within classes, the frequency that teachers make pupils work together in same-ability groups (e.g. higher-achievers sit together on one table and the lower-achievers sit together on another)

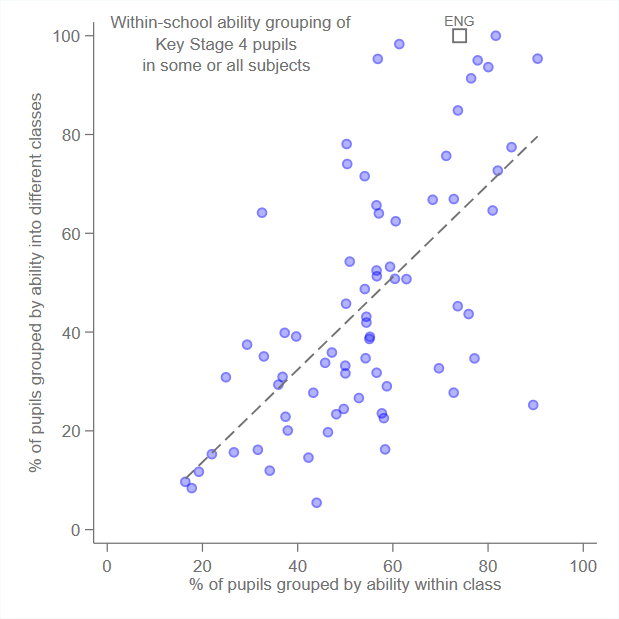

Bringing this information together, we can compare England to other countries in the extent that pupils of different ability are grouped together within lessons at Key Stage 2, Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4. For KS2 and KS3, this analysis covers mathematics lessons only; for KS4 it covers ‘some’ or ‘all’ subjects (the first two from TIMSS, the latter from PISA).

The results are summarised in the graphs below. The vertical axis illustrates how commonly setting/streaming is used, while the horizontal axis shows how commonly pupils are separated into different achievement groups within lessons.

The results are stark. In each graph, England is towards the top right-hand corner.

England particularly stands out in terms of setting/streaming, which is now used for maths in almost half of Year 5 classes and in almost every secondary school. Importantly, these are much higher rates of within-school ability segregation than in other developed countries.

The upshot

Why does this matter?

As the Education Endowment Foundation has noted, existing evidence suggests that some forms of ability grouping (most notably setting/streaming) is not beneficial for pupil achievement.

Those who are least likely to benefit, and most likely to suffer negative effects, are low-achieving disadvantaged pupils who get placed together in the bottom group/set. This, in-turn, is likely to undermine government attempts to reduce educational inequality and enhance social mobility.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

I refer you to Andrew Old’s outstanding contribution to this argument – where he systematically takes apart the EEF’s meta meta analysis and shows that it is completely inaccurate.

https://teachingbattleground.wordpress.com/2018/04/02/the-eef-were-even-more-wrong-about-ability-grouping-than-i-realised/

The increasing evidence from cognitive science, which has its background right from Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, where we must look at the ‘sweet spot’ to encourage learning just beyond the known; and from the cognitive overload work from Sweller et al, as well as from the clear message from psychologists such as Dan Willingham, which makes it clear that if two students have vastly different prior knowledge, and you try to teach them the same stuff, the student with less prior knowledge will be in cognitive overload and will struggle… a spread of 32 students with wildly differing abilities (in a secondary mixed ability class) is impossible to cope with effectively.

If we narrow the ability range by setting (only narrow it – we must always remember that ALL classes, even set classes, are still mixed ability – just a narrower range), then we avoid the potential for this cognitive overload and are far more able to both challenge the quicker learning more able, while better support the less able (typically in a much smaller group).

It makes perfect sense to set.

Thanks for the comment Nigel.

I agree that there is a lot more work to be done here.

The main point of the blog was to try and point out that we stand out in this respect internationally. So if ability-grouping is a negative (or a positive) thing is a particularly important thing for us to know…..