In a previous blogpost, we looked at which schools were entering pupils for GCSE early – generally in Year 10 – and suggested that the effect of early entry was around a third of a grade lower in the subject entered early.

But what’s the effect of early entry on overall attainment? Perhaps the cost of a lower grade in one subject is outweighed by gains in others?

Reasons I hear for these 'early entry' policies include – "it gets one out of the way so they can focus on fewer in y11"; "it gives them the chance to understand the volume/level of study required to pass a gcse" and "leaves more lesson time for other subjects in y11"

— Yorkshire Steve (@Yorkshire_Steve) August 20, 2019

We can use 2018 end of Key Stage 4 data to identify four groups of pupils who were entered for GCSEs early by subject:

- English language or literature

- A modern foreign language excluding French, German or Spanish (these tend to be community languages)

- Statistics

- Any other subjects

Inclusion in these groups is done on a strict basis – pupils must be in one and only one of the groups. This means, for example, that pupils entered early for both English language and a community language are not included.

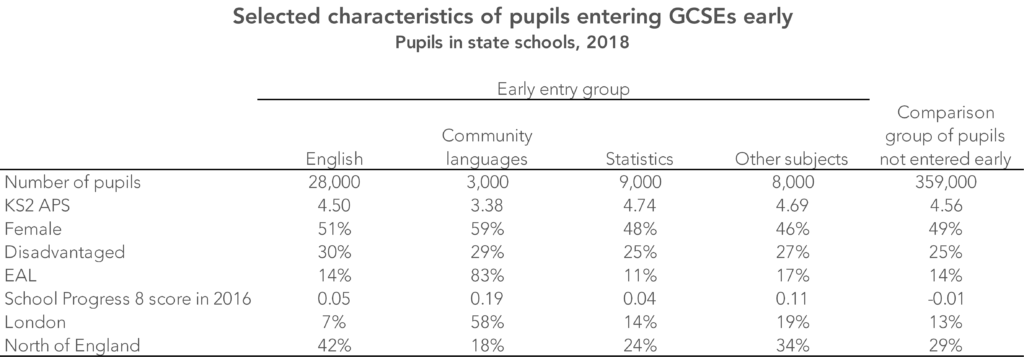

The table below shows how pupils in the four groups above compare to pupils who attended schools which tended not to enter pupils early in terms of characteristics.

We can see that pupils in the north of England tend to be over-represented in the group entered early for English.

Pupils in London, and pupils with a first language other than English, are over-represented in the community languages group.

Pupils entered early in statistics and other subjects tend to have a higher than average Key Stage 2 average point score. And across all four groups, pupils tend to be from schools with above average Progress 8 scores back in 2016.

Creating comparisons

We can match pupils in the four groups to pupils at schools which tended not to enter pupils early, on a range of pupil characteristics and school characteristics, to see how their attainment differs.[1] In other words, comparing similar pupils in similar schools.

Pupils are only included in the comparison group if they entered the qualification we’re looking at in summer 2018. For instance, the comparison group for pupils who entered statistics early only includes pupils who entered statistics, in Year 11, in summer 2018. The exception is for the “other subjects” group. Because of its diversity, all pupils who entered GCSEs in 2018 are included in the comparison group.

Impact on overall attainment

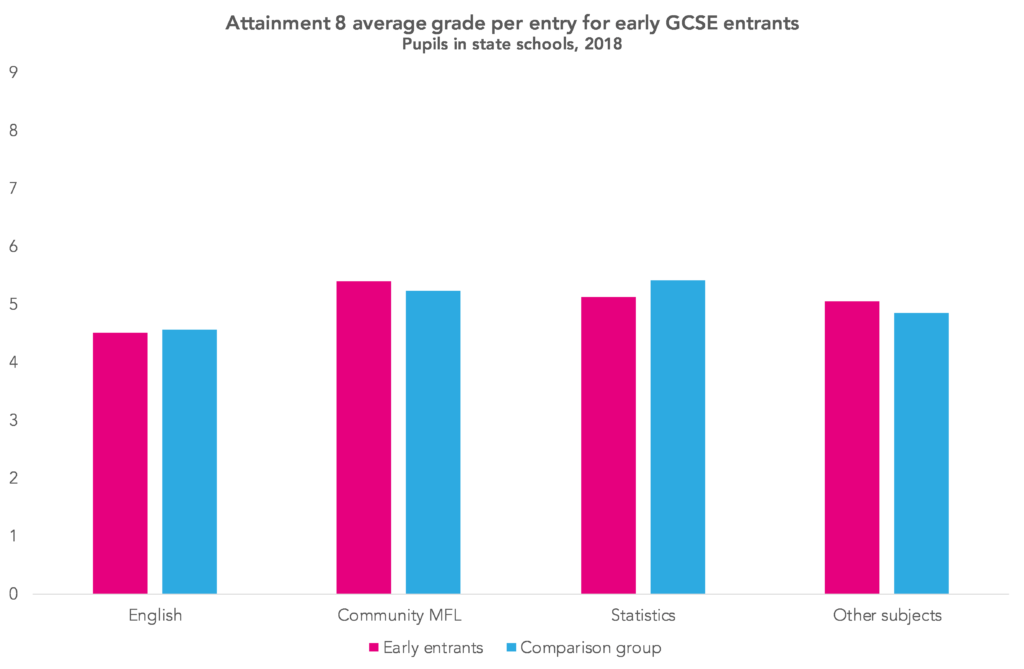

So what is the effect of early entry on overall Attainment 8 scores?

It is fair to say that the results are mixed.

Early entrants in English and statistics tend to have lower overall attainment. For the statistics group, 0.3 grades per subject. For the English group, the difference is much smaller – 0.06 grades per subject.

However, early entrants in community MFL and other subjects achieved higher overall attainment – around 0.2 of a grade higher, as the chart below shows.

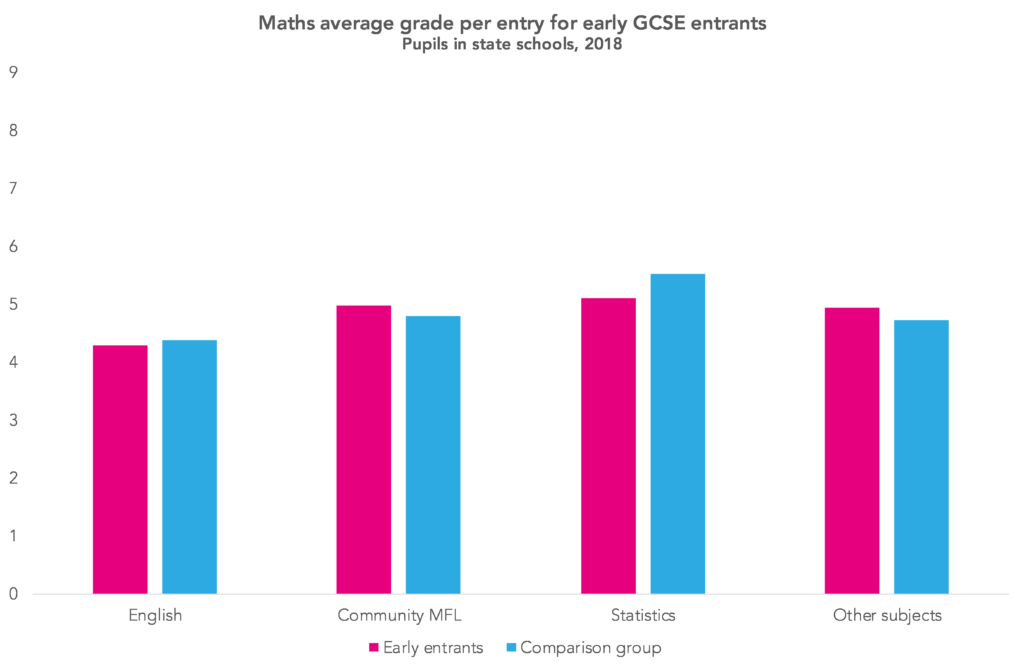

Broadly similar things can be seen focusing just at pupils’ attainment in English and maths, as shown in the next two charts.

At this stage, we are not sure what to make of this. It is possible that these differences reflect some unmeasured difference between the groups that we have not controlled for. However, we would be interested to hear any views about why early entry in statistics might lead to lower overall attainment.

Impact for disadvantaged boys

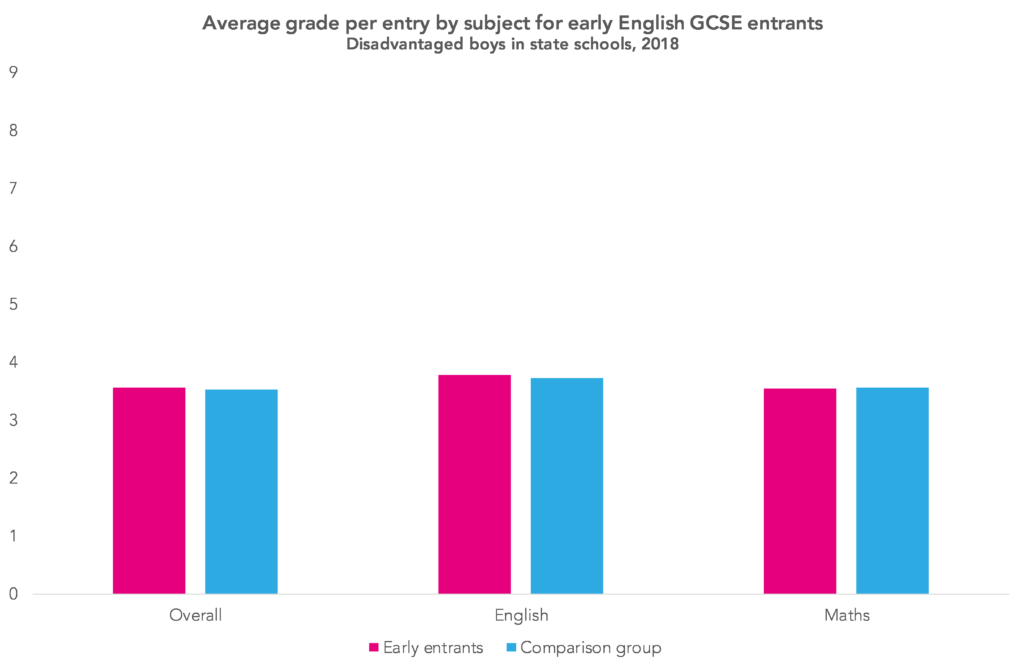

One argument we hear for early entry in English is that it has benefits on overall attainment for disadvantaged boys. The idea is that under Progress 8, the highest grade of English language or English literature is doubled provided that both are entered. So one is entered early “to get it out of the way” leaving more time to concentrate on other subjects in Year 11.

So let’s repeat our analysis for pupils entered early in English, this time only including disadvantaged boys.

Overall, and in English, early entrants achieved fractionally higher outcomes, as the chart above shows. In English, for example, the difference was 0.05 of a grade.

Summing up

It is fair to say that the picture presented here is mixed.

In English, the subject most likely to be entered early, it does not look like there is an overall effect of early entry but there might be a small benefit for disadvantaged boys.

All of this rests on how good the matching process is at creating appropriate comparison groups. We have included a range of pupil-level and school-level characteristics but we may be missing something important that is (at least in part) driving the differences in attainment we see in the charts. Let us know if you think this is the case.

Want to stay up-to-date with the latest research from FFT Education Datalab? Sign up to Datalab’s mailing list to get notifications about new blogposts, or to receive the team’s half-termly newsletter.

1. Covariate balancing propensity score matching is performed to reweight the comparison group so that it balances each treatment group in terms of the pupil characteristics and school characteristics.

The pupil characteristics used are: KS2 APS, gender, first language (English/other), ethnicity, IDACI score, eligible for free school meals in last six years.

The school characteristics used are: government office region, cohort KS2 APS, % disadvantaged pupils, % EAL pupils, Progress 8 score in 2016 (when the cohort started KS4).

Another reason for early entry that I have heard, is for those ‘becoming disaffected’ usually disadvantaged boys and therefore in danger of achieving much less in Y11. Early entry at least gives them something. Numbers in this category would presumably be small, but might account for the marginal advantage shown above.

Interesting article. Why is early entry so prevalent for statistics? It’s three times more popular than community languages.

The benefits for early entry into community languages, and probably native, languages is clear. The logic for statistics escapes me though. Does it benefit later maths entry?

Results in statistics are largely believed to be higher and easier to get. Consultancy networks of school advice groups such as Pixl have often recommended it as early entry as way of gaining higher overall outcomes which has outcome of lots of schools changing patterns of entry en masse.